(John McCann)

There is no shortage of women with the skills required to lead at universities, but they are not ascending to leadership positions.

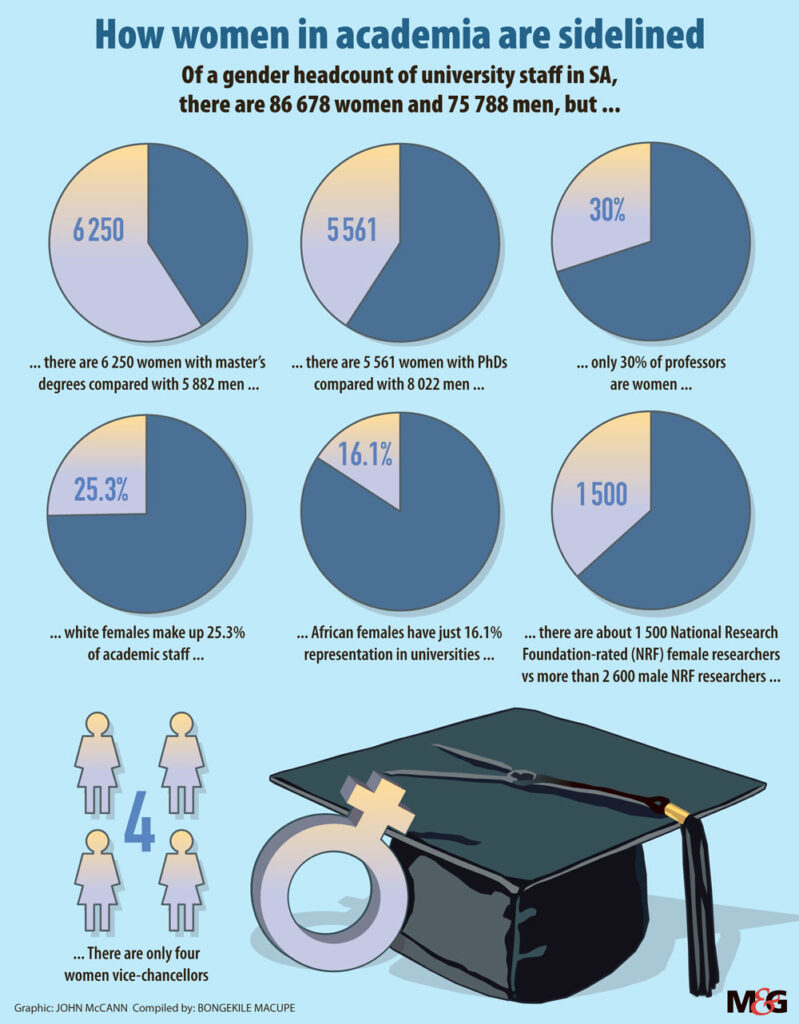

South Africa only has four women vice-chancellors out of 26 universities.

The acting head at the Thabo Mbeki African Leadership Institute, Dr Edith Phaswana, said women are made to feel that they should be grateful just to be in the higher education sector and that they should not expect anything more.

Phaswana said it was disheartening that academics had much to say when it was the government perpetuating inequalities, but that society learned about exclusion and inclusion from academia.

“When it is reflected in our societies, we act as if we are surprised, but this is what academics live daily. We are all aware of the disparities according to race and gender, which continue in many of our universities. In terms of the workload, women pay a high price for unrewarded, unappreciated academic citizenship.”

At a webinar hosted by Higher Education Resource Services (Hers-SA), an organisation dedicated to advancement and leadership development in the higher education sector, and Universities South Africa (USAf), it emerged that since 2015 there have been 20 vacancies for vice-chancellors and that only four women filled those positions.

“That tells us a story about how we view the role of women in higher education, particularly in leadership positions. This is something that we should not normalise. In 2020 we still have a picture that does not resemble the demographics of this country nor the demographics of higher education,” said the chair of the Transformation Managers Forum at USAf, George Mvalo.

He added that there were more women in academia in terms of headcount and that more women held master’s degrees as their highest qualification than men.

Mvalo said there were 12 women in deputy vice-chancellor positions, out of about 30 positions. It is troubling that men have filled all vice-chancellor vacancies that were left by women over the past five years.

“The argument that we cannot find women to lead universities is a blue lie, and it must be debunked. There are more women than men in higher education. They are at deputy vice-chancellor, dean as well as head of department [level]. So there is sufficient capacity and talent that resides within our 26 public universities.”

Last month the department of higher education, science and innovation released a report compiled by the ministerial task team on the recruitment, retention and progression of black academics at South African universities, which found that numbers of black and female academics at universities were growing at a slow rate.

The report found that white females are overrepresented at 25.3% of the academic staff, compared to their 4.5% slice of the general population. In comparison, black women academics are the most underrepresented group at 16.1%.

University of Zululand vice-chancellor Professor Xoliswa Mtose — who was part of the Hers-SA webinar — said it might well be that there are many women at universities, but that these women are appointed in lower positions.

“The majority of these women are in support services with most of the services constituting menial jobs that include making tea for us as bosses. How different is this approach to the apartheid approach to gender inequality? These women are included in appointment statistics to give an impression that there is progress, yet the numbers by themselves are misleading.”

Mtose added that it was not surprising that “in a country built on the bedrock of racism and patriarchy there are only four women vice-chancellors”.

The other three women vice-chancellors are Professor Sibongile Muthwa from Nelson Mandela University, Professor Mamokgethi Phakeng from the University of Cape Town and the University of Mpumalanga’s Professor Thoko Mayekiso.

Marissa van Niekerk, the acting chief executive officer of the Commission for Gender Equality, said findings from the transformation hearings it held with universities between 2014 and 2019 revealed that succession plans did not target women and people with disabilities.

Van Niekerk said the commission’s findings also found that universities are struggling to increase the representation of women, especially black women in senior management.

The director of Hers-SA, Brightness Mangolothi, told the Mail & Guardian that the entrenched institutional, patriarchal culture was the stumbling block for women ascending to leadership positions.

She said young, vibrant women who have the qualifications and skills to lead are blocked by men who say they are women, young and cannot tell them what to do, or tell them that they are black and do not belong in the university space.

She said silencing women in the education space by, for instance, not valuing their input was a concern.

Mangolothi said her PhD focused on workplace bullying in higher education. She found that women are often given “care work”.

“Because you are a woman they expect you to take down minutes, regardless if you are a dean or a head of department or you are a director within the institution.”

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

The perpetrators who seek to exclude or other women in the system also use students, and this manifests with students complaining about women lecturers or heads of department. When cases are followed up, it is discovered that they were orchestrated. Men manipulate students to advance their cause, according to Mangolothi.

Men who bring in funding or grants use this fact to continue oppressing women academics.

“Some men have the audacity to tell you in your face that the system will rather have you, as a woman, outside instead of getting rid of them ‘because I am paying for your salary’.”

Mangolothi said in the past the excuse was that women are not prepared for leadership positions or are not qualified. Yet she said she engages with many women who are qualified but find the politics of the system were not enabling them to lead. These women are instead focusing on establishing their research output instead of taking leadership positions.

‘No political will to deal with gender issues’

There is a lack of political will to deal with gender transformation at higher education institutions, even though there have been several ministerial reports dating from as far back as 2008 detailing what needs to be done to confront this challenge.

Even before the reports, talks about transformation in the sector date to 2007 but 13 years later the sector has nothing to show for it.

“The time for the department of higher education to bemoan the fact that there is slow transformation in higher education is over,” said George Mvalo, chair of the Transformation Managers Forum at Universities South Africa. “The department and the ministry need to execute the powers that they are given by the legislation. We also need to implement the regulations of all summits.”

On its part, the department of higher education, science and innovation acknowledges that transformation — particularly for black, women academics — is moving at a snail’s pace.

In the latest report, the department made what it called the “most important recommendation”, which acknowledges that there is a need to “tackle institutional and individual racism and sexism”.

“This means moving from hoping that this will happen naturally to actually putting measures in place to ensure it happens. Universities must interrogate how institutional cultures and traditional practices may be creating alienating environments that intentionally or unintentionally work to exclude, and put proactive measures in place to address this.”