South African sign language (SASL) is the smallest recognised language in South Africa. Although some of the country’s Deaf organisations claim that more than one million South Africans use this language, the 2011 census survey records only 234 655 citizens who use SASL as a “first spoken language”.

This number may include naturally hearing children of deaf parents. By implication, the estimated figure includes citizens who use SASL as an additional language, including hard-of-hearing citizens, as well as hearing citizens who have learned the language as a result of regular contact with deaf people.

As such, SASL ends up as a language of more or less the same order of magnitude as Ndebele (1 090 223 speakers), Swati (1 297 046 speakers) and Venda (1 209 388 speakers), in other words, within the group of “smaller” South African languages.

One could also include the Non-Bantu Click Languages, like Nama. Unfortunately, the census does not yet list this language group separately, despite the constitution’s recognition of it. Citizens who use a language such as Nama as their first spoken language fall under the census category “other languages” (828 258 speakers), together with languages such as French and Hindi.

Promoting SASL will highlight other small languages

The question of whether it is important to promote SASL, therefore, also has implications for South Africa’s other smaller languages and smaller languages in general. However, our constitution does not draw any distinction between recognised South African languages in terms of size, but rather follows an egalitarian approach by envisaging the promotion of the recognised languages, regardless of their size.

Section 6 of the constitution specifically entrusts the Pan South African Language Board (Pansalb), a statutory body, with this responsibility, by requiring the board to promote the 11 official languages, the Non-Bantu Click Languages (including Nama), as well as “sign language [sic]” (by implication SASL) and, at the same time, create conditions for their development and use.

From a language planning point of view, this is already a particularly ambitious assignment; in addition it is one that is assigned to a statutory body — institutions about which there is a healthy degree of cynicism in South Africa, given their dubious performance since 1994. Just think of the current debate on the public protector.

Nevertheless, according to the language sociologist Harald Haarmann’s Ideal Typology of Language Cultivation and Planning, governmental and statutory institutions are relatively more effective with language promotion than NGOs and non-statutory institutions, such as pressure groups, language organisations and individuals.

Effectiveness in this typology rests on a well-worked language plan that is indeed implemented. Where such institutions fall short, it goes without saying that NGOs and non-statutory institutions will have to step in to save the day.

In light of Pansalb’s constitutional mandate, the question of whether it is important to promote SASL (and the other listed languages) is, in fact, irrelevant. This is important, because the constitution requires it — it is that simple.

One should, therefore, rather ask why the constitution considers the promotion of the three mentioned groups of languages important.

The constitution promotes languages

The constitution links language promotion to language development and language use (in this case not how the language is used, but that the language is used; that is language spread).

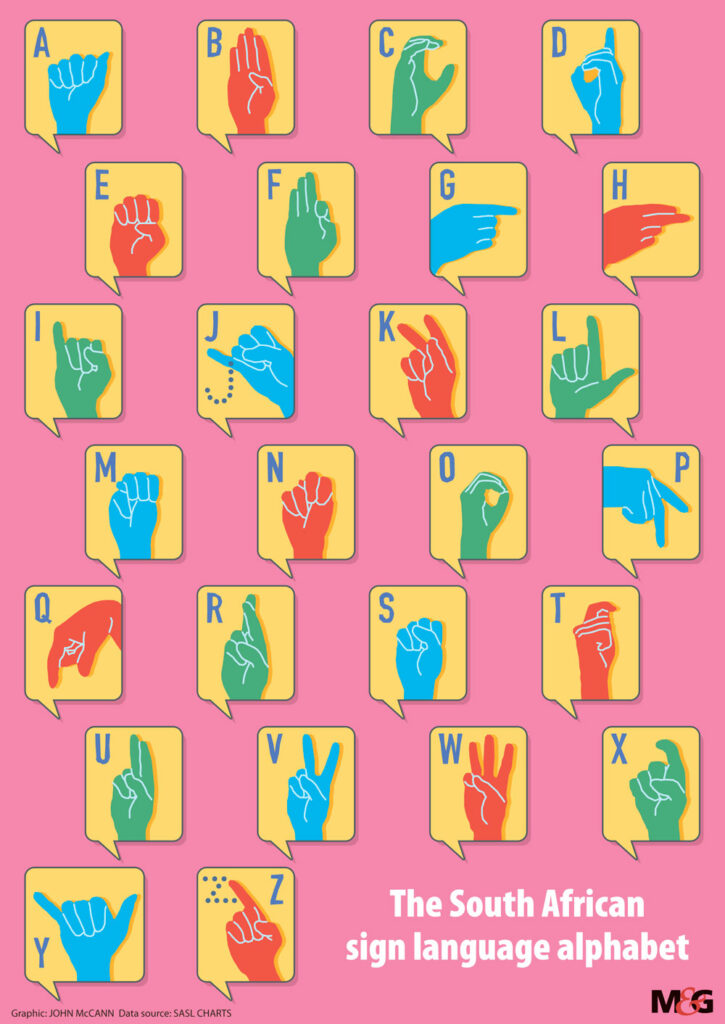

In language planning terms, language development refers to the development and standardisation of the language corpus and language code. These include the development of a writing system, grammar, glossaries, dictionaries, terminology, curriculums, literature and so on.

Such development is a prerequisite for the use of the language in education, both for teaching the language and the language as means of instruction.

Language spread refers to how the language spreads through increasing use by the community within different contexts. Teaching also plays an important role in this: Is the language taught as a subject, but also as an additional or foreign language? (In language sociology, a foreign language is regarded as a language that the learner does not actually hear or use in their daily life.)

There is, therefore, clearly a complicated relationship between language development and language use spread — the more different people in different contexts use the designated language and the more it develops, the more people will want to use it in a variety of contexts.

One way of trying to answer why the constitution considers the promotion of a language such as SASL important, is to look at the individual language rights the constitution grants, as contained in the Bill of Rights.

1. Section 29 of the Bill of Rights guarantees the right of education in the official language(s) of your choice. Although SASL is not (yet) an official language in South Africa, the South African Schools Act stipulates that the language is regarded as an official language for the purposes of learning in a public school. This provision, therefore, requires that SASL be developed for teaching purposes and that such development be promoted.

The institutionalisation of SASL as a home language since 2014 is an example of the effective promotion of the language by both a government body, in this case the department of basic education, and a statutory body, quality assurer Umalusi.

However, to promote the use of SASL, the language should now also be taught as an additional language. The Use of Official Languages Act paves the way for this by requiring state institutions, as well as statutory institutions, to be able to communicate effectively with members of the public who choose to use SASL.

This can be achieved through professional interpreting services, but also through programmes that develop language skills in SASL, as is currently the case at some South African universities. Pansalb’s SASL Charter also promotes this objective.

2. Sections 30 and 31 of the Bill of Rights guarantee the cultural rights of the use of the language of your choice within the community and organisations of your choice. The responsibility for language promotion actions in these contexts rests on the shoulders of pressure groups, cultural institutions and individuals.

Organisations within the deaf and hard of hearing community play an important role in this, but ideally Pansalb would play a more prominent role, as well as institutions such as the South African Human Rights Commission with the Commission for the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Cultural, Religious and Linguistic Communities. Pansalb’s SASL Charter can also play an important role as an instrument of language promotion.

3. Section 35(3)(k) of the Bill of Rights guarantees a court hearing in a language that the accused understands or, when this is not possible, to have the proceedings interpreted in that language. Now that South Africa’s chief justice has proclaimed English as the language of record in courts, the first part of the provision largely falls away.

A dignified interpreting service requires well-trained SASL interpreters with appropriate language skills. Pansalb’s SASL Charter has a lot to say about the serious shortcomings in this area for the kind of language promotion provided by the constitution.

4. Section 35(4) of the Bill of Rights guarantees information to an arrested, detained and accused person in a language that the person understands. Given the current state of South Africa’s police service, one can only imagine how difficult it is to exercise this right, hence Pansalb’s SASL Charter also envisages extensive promotion actions in this regard. Here too, a lot of language promotion work awaits.

Is it important to promote SASL? From this factual overview we note why the drafters of the constitution consider the promotion of SASL to be important. Apart from the fact that such promotion actually contributes to the realisation of language rights in the Bill of Rights, it also contributes significantly to the realisation of the ideals of the constitution, as contained in its preamble.

The aim to “increase the quality of life of all citizens and unlock the potential of every human being” in particular catches one’s eye. The promotion of SASL is, therefore, important; moreover, it serves a noble cause.