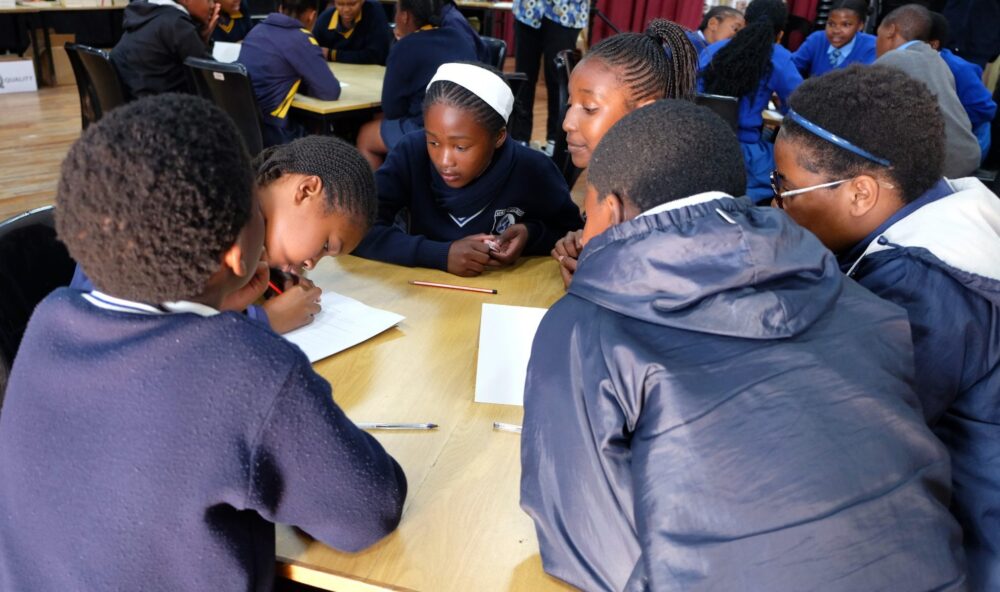

Aced it: The winning Grahamstown Adventist Primary School team at

the Phendulani Literary Quiz. Photo: Nozipho Maphalala

Lucky Xaba, the Humanities librarian at Rhodes University, arrives at a no-fee school in Makhanda to check on the colourful classroom library she and her team built a few months before.

The teacher is absent, but the Grade 1 children are there, reading independently on cushions. These are isiXhosa Grade 1s in a country where only 13% of children who speak an African language can read for meaning by the end of Grade 4.

Xaba’s conclusion: “They are already becoming independent readers because they have access to good books.”

The Rhodes Library and NGOs, the Lebone Centre, have established more than 40 Foundation Phase classroom libraries in Makhanda.

But there are more than 160 FP classrooms in the city. The Eastern Cape Department of Education hasn’t built a single library.

The simple math of access

A classroom library with 100 high-quality books costs about R20 000. Over five years, serving 175 learners, this amounts to R114 per learner, which is less than 7% of the R1 750 annual allocation that the National Education Minister mandates provinces spend per learner.

In the Eastern Cape, the Department of Education (DOE) has withheld a large proportion of the funding from its fee-exempt schools — about R5 billion since 2020 — on the pretext that its “centralised procurement” strategy is providing scaled resources for all schools in the province.

Fewer than 3% of retail book sales for children are in African languages, despite 80% of the population speaking African languages at home. Publishers cite insufficient demand because schools and libraries aren’t buying, creating a vicious cycle.

Research shows that classroom libraries increase reading frequency by 70% compared to centralised libraries. International “book flood” studies demonstrate that having plentiful books in classrooms produces literacy gains. Books are accessible, teachers integrate them into lessons, children borrow them easily and there’s no intimidating journey to restricted-hours facilities.

Investment in classroom libraries would also stimulate an explosion in the African language book industry — authors, illustrators, designers, and established and start-up publishers could flourish.

Rhodes University Humanities and Education librarian Lucky Xaba (right) puts the finishing touches to one of the several Foundation Phase classroom libraries built by her Siyafunda eMakhanda project team. Photo: Rod Amner

Rhodes University Humanities and Education librarian Lucky Xaba (right) puts the finishing touches to one of the several Foundation Phase classroom libraries built by her Siyafunda eMakhanda project team. Photo: Rod Amner

Magic of quality books

In September, the Lebone Centre sent 12 high-quality children’s books to five primary schools. After devouring the volumes, five Grade 6 teams from various schools competed on 40 questions about the books.

Walter Mapfumo, the winning teacher from Grahamstown SDA School, reports: “The extent to which it has stimulated the love of reading in our learners is quite profound. We face the pandemic of learners failing to read for meaning, but the books and the opportunity to participate in the quiz have created a culture of independent reading in the school. The ever-growing enthusiasm for reading amongst our learners has taken a life of its own.”

Everyone in his class read the books, not just quiz participants. When children who supposedly “don’t read”; receive great books they become readers.

The success highlights the failure of South African education: after the Foundation Phase, formal reading instruction disappears — and so do the books. When children should transition from “learning to read” to “reading to learn” — and crucially, to reading for pleasure — the scaffolding vanishes.

The Siyafunda eMakhanda classroom library at Makana Primary School was built by Rhodes librarians with funding from the Sali Trust. Photo: Rod Amner

The Siyafunda eMakhanda classroom library at Makana Primary School was built by Rhodes librarians with funding from the Sali Trust. Photo: Rod Amner

Reading must continue

Evidence of our systemic reading failure extends through secondary school. At a Makhanda school, Grade 12 learners studying the Fugard play My Children, My Africa had no copies of the text, despite the availability of free online digital versions. They hadn’t watched the play (available for free on YouTube) or accessed online study guides. The teacher taught plot summaries instead.

Rhodes University students report learning summaries of their complex isiXhosa school set works for exams rather than reading the full books.

The 21st century saw YA literature’s “golden age” — Harry Potter, Hunger Games, plus African digital platforms like Jalada revolutionising access. South African authors like Lauren Beukes and Edyth Bulbring, as well as series like Fundza’s Harmony High, have hooked young readers. However, these books are often absent from most public libraries and schools.

Literacy researcher Maryanne Wolf demonstrates that deep reading fosters empathy and critical thinking through sustained engagement with books — essential skills for navigating life and democracy.

The Grahamstown Adventist Primary School team digs deep for answers at the Phendulani Literary Quiz. Photo: Nozipho Maphalala

The Grahamstown Adventist Primary School team digs deep for answers at the Phendulani Literary Quiz. Photo: Nozipho Maphalala

Rhodes survey revelation

A survey of 300 first-year Rhodes University Journalism students earlier this year reveals a stark divide between those who learnt to read as a “survival strategy” to pass exams and those who discovered reading for pleasure. The survivalists reported significantly lower university preparedness.

Surprisingly, heroes for the readers were digital platforms like Wattpad and social media. Students who read on their phones, discovering stories that reflect their lives and languages, tend to show stronger academic outcomes. Most tellingly, strong readers mention one factor: access. Whether through libraries, classroom collections or phones, successful readers found books somewhere, somehow.

Rhodes University Humanities and Education librarian Lucky Xaba speaks at the opening of a Grade 1 classroom library built by her Siyafunda eMakhanda project team. Photo: Rod Amner

Rhodes University Humanities and Education librarian Lucky Xaba speaks at the opening of a Grade 1 classroom library built by her Siyafunda eMakhanda project team. Photo: Rod Amner

Digital goldmine

On every teacher’s government-issued laptop lies potential access to thousands of free stories and audiobooks in 11 languages.

Nal’ibali offers multilingual stories and audiobooks online and distributes them on WhatsApp. Book Dash creates open-source picture books. African Storybook provides downloadable books in African languages. Fundza targets teenagers, with locally written books and stories.

Research in Makhanda reveals that most librarians and teachers are not aware of the resources. If teachers loaded the free collections onto their laptops, they could send stories weekly to parents via WhatsApp with simple instructions: read this to your child or let them read to you. For parents who lack confidence in reading, audiobooks and read-aloud videos are ideal options.

Most parents have phones; In Makhanda, high-speed uncapped fibre costs just R5 a day. Teachers could encourage parents to download free literacy apps and access thousands of read-aloud YouTube videos.

Simple solutions

In Makhanda, GADRA Education’s QondaRead programme shows what’s possible with basic technology. They provide classrooms with portable, lockable data projectors and speakers. Teachers project lesson materials, including books and videos, onto classroom walls.

Imagine combining physical classroom libraries supplemented by digital projection, teachers sending stories to parents’ phones, audiobooks for struggling readers and videos modelling reading techniques.

A raft of NGOs, all ready to guide book selection, are operational. IBBY South Africa and the Puku Foundation focus on indigenous language books. The South African Literary Awards (SALA) provides annual shortlists. UNISA’s Children’s Literature Awards promote African language stories.

Nal’ibali maintains a searchable database of recommendations filtered by age, language, and theme. Fundza has become an expert in teen literature. .

One day of training could show every teacher how to access free resources, load them onto their laptops and share them via WhatsApp.

Libraries could operate to Grade 12. The DOE could fund the creation of read-aloud videos in African languages. Projectors could display stories and play audiobooks.

Implementation gaps

The big NGOs driving content creation work in silos. Nal’ibali focuses on communities, not schools, and Fundza bypasses schools to reach teens. No mandate exists for the use of digital resources in schools. No training is provided.

While NGOs produce world-class content, it often fails to reach classrooms. While parents have phones capable of receiving daily stories, they typically receive only homework notifications. Much of the content is free. The technology is affordable. Organisations stand ready to guide book selection. Parents have phones. Teachers have laptops.

The question isn’t whether South Africa can afford to transform literacy — it’s why available solutions remain unimplemented. When Grade 1s with books become independent readers, when Grade 6s devour quiz books so enthusiastically that their teacher reports minimal preparation is needed, the message is clear: children will read when given the chance.

The features were made possible by the Henry Nxumalo Foundation who funded the Between the Lines series.