Emissions: Eskom cooling towers in Mpumalanga contribute to the entity’s status as a top polluter. Photo: Waldo Swiegers/Bloomberg/Getty Images

There are no lawsuits against fossil fuel companies for the current climate damage Africa is experiencing as a result of historical emissions, but academics and rights groups think this is not off the cards for the world’s most vulnerable populations.

Successful recent lawsuits in the Netherlands, Germany and elsewhere have seen courts demand countries and companies dramatically strengthen climate targets.

These lawsuits are not the same as suing a mega-polluter for its role in what climate change is doing to people’s lives and livelihoods at present. Litigation for compensation as a result of current losses and damage from climate change have not yet been successful, and researchers argue that this is a result of poor scientific attribution to prove causal relationships in court cases against the world’s biggest carbon emitters.

Greenhouse gas emissions are the fault of a collective system but in other parts of the world, people are suing fossil fuel companies for damages. A study published on 28 June has found that lawsuits seeking financial rewards for loss and damage from big polluters are required to prove that the corporation in question is directly responsible for a community’s or person’s losses — which lawyers are failing to do largely due to poor scientific attribution.

To prove what has caused the plaintiff’s losses, lawyers must use updated attribution science to prove the link to historic emissions. Attribution science allows scientists to calculate how emissions contributed to specific events such as storms, droughts, heat waves or floods. For example, recent research found that human-caused sea-level rise increased the damages suffered when Hurricane Sandy hit the US east coast, in 2012, by $8.1-billion. Another study found climate change was responsible for $67-billion of the damage caused by Hurricane Harvey, which hit Texas in 2017.

In a study titled Filling The Evidentiary Gap in Climate Litigation, published in Nature Climate Change, a leading interdisciplinary science journal, the authors said that plaintiffs have brought more than 1 500 climate-related lawsuits worldwide, and the number of claims filed continues to increase.

Tracy-Lynn Field, a professor at the school of law at Wits University, said quantifying climate change damage to Africa would be an interesting exercise. She recently wrote a paper on climate litigation in Africa and says the new report is important for strengthening these cases.

“The paper is saying they are not using attribution science and if they did they would get over the hurdle of causation. I agree, but if you look at the cases that were analysed, fewer than fifteen cases are in Africa — and those cases have not been about causality,” she said.

Fossil fuels are a contentious issue, Field said, as the continent is responsible for only 4% of historic global emissions compared to the world’s wealthiest countries.

“This doesn’t mean [South Africa] won’t do it eventually. The main culprits are Eskom and Sasol, and the banks that finance them, and their shareholders,” Flynn said.

South Africa’s cases are only related to environmental assessment compliance and regulatory compliance. The botched Thabametsi coal development in Mpumalanga was a milestone for climate considerations in litigation when a high court ruled that the assessment failed to consider climate change.

If litigation for damages becomes a reality in South Africa, Sasol and Eskom, the country’s biggest polluters, are highest at risk of becoming respondents.

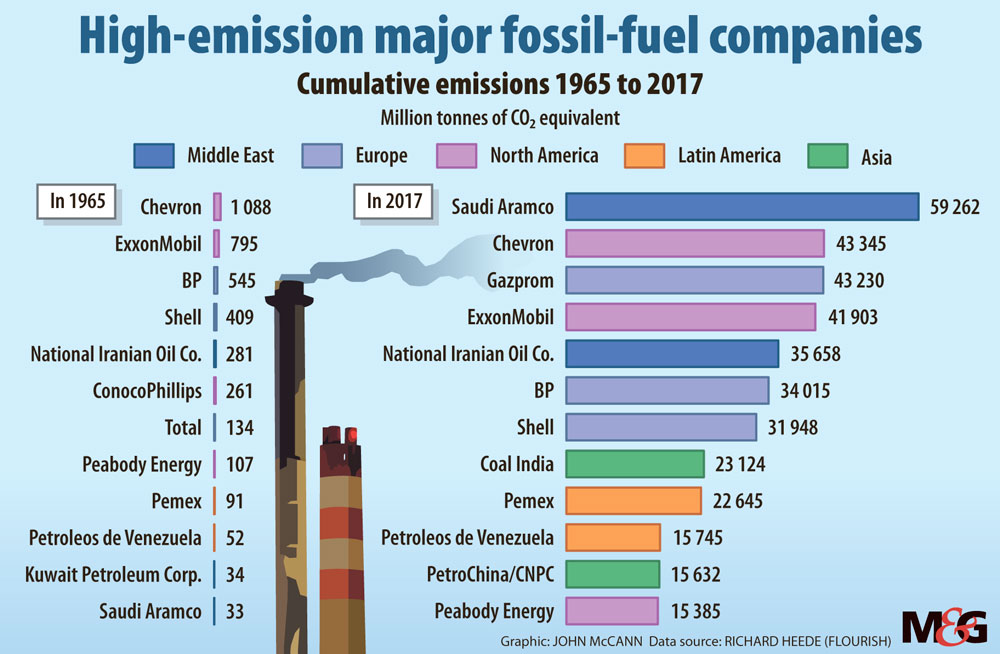

The Carbon Majors Project is an example of correct quantification of fossil fuel companies’ historical emissions. Such emission allocations, coupled with input from climate scientists and correct attribution for causality, are key to successful litigation, argues the report.

It highlights that existing scientific findings, such as the research that calculated the proportion of temperature increase and sea-level rise that can be attributed to emissions from individual companies, including ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell and Saudi Aramco, are there for lawyers to present to the court.

“The power of climate litigation is increasingly clear,” said lead author Rupert Stuart-Smith.

Stuart-Smith said lawyers must make more effective use of scientific evidence. Climate science can answer questions raised by the courts in past cases and overcome hurdles to the success of these lawsuits.

The delay in carbon’s heating effect on the planet means that the effects of current emissions will only be felt in the future. There is a difference between existing loss and damage by big polluters in the US, UK and Asia, who carry the historical contribution to emissions that made the current crisis, and emissions from newer emitters in emerging economies, whose emissions will contribute climate impacts in the future.

Both human rights groups and scientific experts are of the view that holding high-emission companies accountable for their contribution to climate change is key to driving systemic change and to protecting those most vulnerable to climate change.

“Climate litigation aimed at generating accountability is on the rise, but the results have been mixed,” said Professor Thom Wetzer, founding director of the Oxford Sustainable Law Programme.

The report argues greenhouse gas emissions and climate-change impacts result from the cumulative emissions of multiple parties.

“This underlies the use of ‘market share theory’, an approach which, following precedent in pharmaceutical and tobacco litigation, allocates damages among defendants according to the portion of emissions for which they are responsible.”

The report recommends that attribution-science evidence quantifying individual defendants’ contributions to plaintiffs’ losses directly should be used instead of the market-share approach.

The report is a culmination of the first global study of climate-science evidence in lawsuits. It identifies the evidence needed to make causal arguments and analysed evidence in 73 cases across 14 jurisdictions.

Tunicia Phillips is an Adamela Trust climate and economic justice reporting fellow, funded by the Open Society Foundation for South Africa