Happy Sindane's body was found a few hundred metres from his home in Tweefontein, Mpumalanga on Monday, 1 April 2013. A family picture of Happy among his adopted family. (Madelene Cronjé)

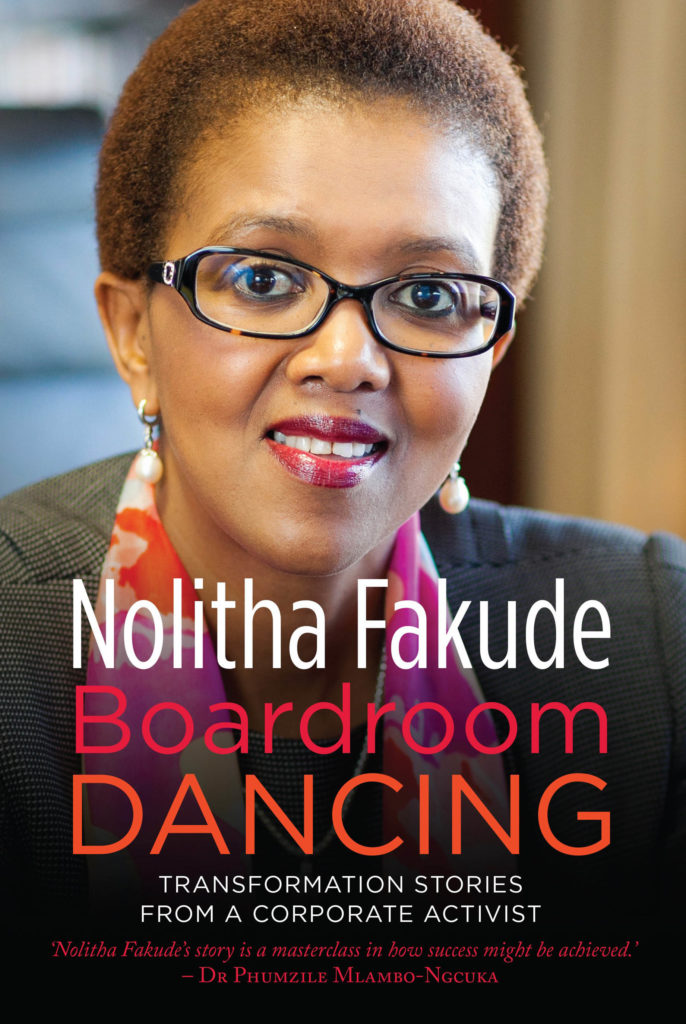

This is an edited extract from Boardroom Dancing: Transformation Stories From a Corporate Activist by Nolitha Fakude (Pan Macmillan)

It was a regular evening in early 2004 and I was preparing for a meeting the next day, enjoying the second wind I usually get in the stillness that comes after dinner, when my phone rang. It was my Aunt Zet.

“Litha, do you have the TV on?” she said, her voice full of excitement. “What’s this about?” I asked, searching for the remote.

Images of a down-and-out white man in his 20s gave way to those of the clapboard façade of my family’s general store back in Cenyu, the village where I grew up in the Eastern Cape. The newscaster’s voice explained that the man had shown up at a police station in Mpumalanga, claiming that a coloured family had kidnapped him, and that he was seeking his white parents.

“It’s your child, Ebbie,” Aunt Zet said, as an image of the blue-eyed boy whom we had called “Happy” filled the screen.

I had no idea how Happy had ended up on TV.

Shocking as it was, his sad story was all too typical in the way it illustrated the brokenness at the root of our country’s history — a profound chasm of structural racism and inequality that I had increasingly focused my professional life on helping to fill.

With a population of about 350, the village of my youth was the kind of place where everyone knew each other. People came to our store to communicate with family members working as migrant labour elsewhere, and I often helped read and write letters or put through phone [calls]. As a result, I often knew more than I should have about people’s personal lives and struggles.

Ebbie’s mother, a domestic worker in Jo’burg, had brought him to Cenyu when I was about eight. Still a baby, Ebbie was left with his grandmother. It soon became obvious that Ebbie was a mixed-race child, the result of an illegal union, according to South Africa’s anti-miscegenation laws at the time. As he grew, Ebbie’s blue eyes and fair skin made him the target of taunts and bullying.

From my family’s shop, it was not unusual for us to hear Ebbie being teased.

The children called him “Amper Baas” (Almost Boss) or worse. Often we would find him crying after having been beaten by boys who resented the idea that this child would someday grow into a white man. His grandmother spent most of her time drinking home-brewed beer, so Ebbie was not only not protected from the bullies, he also was not well looked after.

Maria Skosana whi had been looking after Happy when he was murdered. Happy Sindane’s body was found a few hundred metres from his home in Tweefontein, Mpumalanga on Monday, 1 April 2013. This rock with drops of Happy’s blood was removed from the scene by family members. Madelene Cronjé

Maria Skosana whi had been looking after Happy when he was murdered. Happy Sindane’s body was found a few hundred metres from his home in Tweefontein, Mpumalanga on Monday, 1 April 2013. This rock with drops of Happy’s blood was removed from the scene by family members. Madelene Cronjé

I was at boarding school when most of this was happening, but I knew my mother gave Ebbie food to eat when he came around, and let him ride with her in the bakkie when she went to run errands in town, because he didn’t seem to be in school.

Whenever I was home and saw Ebbie hanging around the shop, I would talk to him and look after him, and people jokingly referred to him as my child.

During my last year at boarding school, when I was 17, I was home helping out in the shop when there was a big commotion outside and I heard people screaming, “Ebbie! Ebbie!” I found Ebbie on the ground, unconscious and foaming at the mouth. I took him to hospital, I found out he had passed out from hunger, and had apparently been eating grass.

Although many people in Cenyu could have been called poor, most had vegetable gardens and there was an unspoken rule that as black people we helped one another. But Ebbie was not seen as a black person.

A couple of months later my mother phoned me and said a social worker had taken Ebbie from his grandmother and put him into foster care. We later heard that a coloured family in town had adopted him, and figured that was the end of the story.

But 20 years later, here was Ebbie on TV, claiming to have been kidnapped. I can only assume that it was the trauma of his childhood that caused him to distort his history and reality. The headlines died as soon as Ebbie got new benefactors in Johannesburg, people who did not think that he was crazy. Sadly, about 10 years later I heard that he had been killed in a shebeen fight.

Despite people teasingly calling him my child, I didn’t know Ebbie well at all. But the unfairness of his treatment in our village left a mark on me. Growing up in our shop, absorbing people’s stories and hardships, I developed empathy and a desire to understand people. I hated knowing that people were treated badly because they were different, and I often thought about all the paths Ebbie’s life could have taken had he simply been born with a different colour skin.

The brokenness of the man who started out as a child who had done nothing worse than have the wrong colour skin in the wrong place at the wrong time was yet another example of the waste and suffering that results from viewing our fellow human beings as the Other; to exclude rather than to develop their potential. Over the years, a question that has come to guide my life is how we can move, as a society, from viewing the differences as a weakness to viewing them as positive so that everyone benefits.