The gift of the gab: Vusi Mchunu's literary works are varied, encompassing translations, essays and poems. (Paul Botes)

Pleiades: Isilimela, the latest collection by South African poet Vusi Mchunu (64), is a piercing autobiographical dance choreographed under the trauma of a terminal illness, fractured friendships and the death of some dear friends. Mchunu was recently diagnosed with cancer — his writing emerges resilient and deliberately pellucid.

The work is a deep personal meditation and a welcome addition to the poet’s growing poetry, literary translation and heritage oeuvre. His previous work includes a collection of poems and essays, Stronger Souls (1990); an English translation of Mazisi Kunene’s Zulu poems, Pipe Dreams (2013); and contributing to curate the Samora Machel Monument at Mbuzini in Mpumalanga.

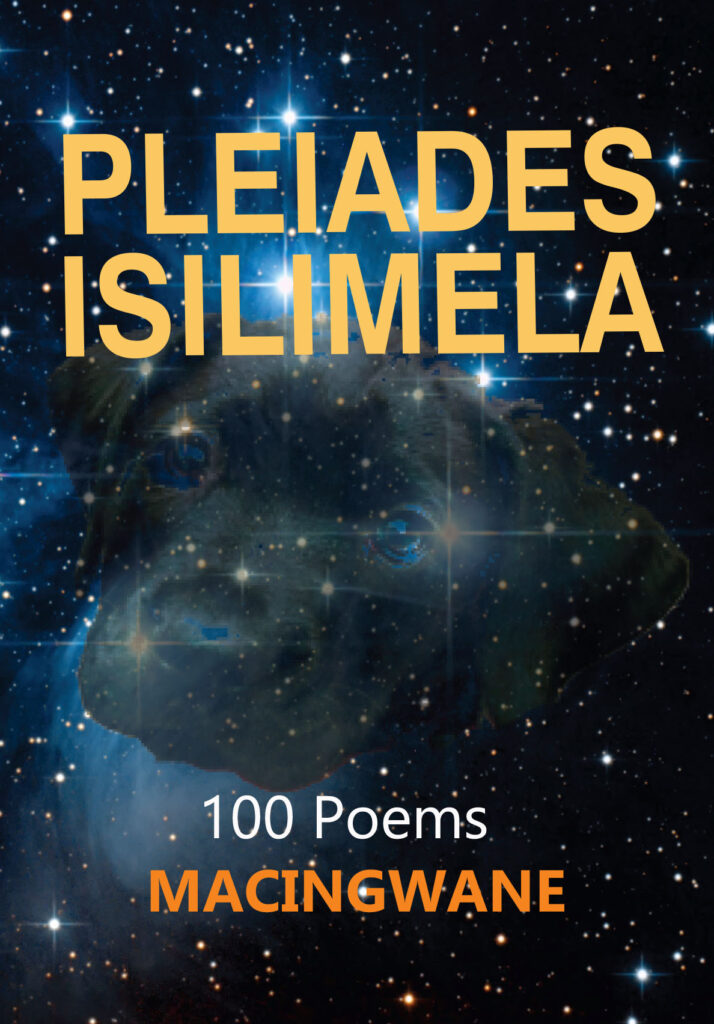

Pleiades: Isilimela: 100 Poems (Africa Now, 2019)This series of poetic love letters — to his wife, family, friends, mentors and an eclectic mix of iconic figures the poet admires — is luminous and insightful. Pleiades: Isilimela is dexterously woven; a kaleidoscope of textures, rhythms and verses. As is often so with someone who has been on the precipice, it is a tad sad — and disturbing. Yet the 100 poems still dazzle, self-affirm, and ask pertinent questions about the human condition, with both a serious and mischievous grimace. The poet is correct to consider himself a “cancer survivor”.

Mchunu writes under his clan name, Macingwane — a heroic avowal of home; his African roots and routes. “I was part of the ground forces of South African Students’ Organisation members countrywide, who worked closely with Soweto student leaders such as Tsietsi Mashinini and Khotso Seatlholo in the build-up to the historic riots of June 1976,” he says in an email conversation between us. We also worked in parts of the Vaal and greater Pretoria.”

Mchunu, who is now based in Johannesburg, grew up in Clermont and attended the famous Catholic boarding school, Inkamana, in Vryheid, from which he matriculated in 1974. He was introduced to Black Consciousness (BC) politics at the University of Zululand in 1975, and he was mentored by BC stalwart Mapetla Mohapi. Mchunu, who himself served time in detention, was deeply traumatised by Mohapi’s death in detention. During his university holidays, Mchunu had worked in King Williamstown as Mohapi’s assistant to support political activists who had just been released from Robben Island and other jails.

“The memory of Mapetla Mohapi’s funeral in Herschel is as vivid as if it was yesterday,” he writes in the email. For a long time I stood silently next to his coffin, forlorn, lost in the heavy weight of my tears.” In 1977 Mchunu fled into exile in Botswana, where he studied at the University of Botswana and Swaziland; then Germany, where he studied dramatic arts and heritage at the Free University of West Berlin.

In a preface to the book, mentor and scholar Abdul Alkalimat says: “I have been with Vusi in Germany, in England, in the USA, and yes, in South Africa. His soul is African while his mind stretches out into the African diaspora and embraces what can only be known through direct experience.”

In Pleiades: Isilimela, the poet is at full throttle, a distant seer reciting a litany of healing mantras, a bold Pan-African vision, a battered black man’s stubborn will to live. And love. In My Cosmic Sign, he writes: “tracing cylindrical zones -popolvuh/ yemanya of the middle –arrow onto that meeting of fate/ when the gobbling gods of greed rudely rise to the y2k nightmare/ the midnight parade of calendars of the south/ the awesome masquerades on stilts, the roar of the jaguar, the roll of sea mothers -an indigenous parade of love …”

The poems are confessional epistles as the poet appreciates the gifts of love in his life, urging readers to grow stronger from every rapture and agony that may threaten balance in their lives. In Back from Separation, dedicated to his wife, Nono, Mchunu writes: “To return from separation is to walk hot coals without flinching/ A polished window, a higher vista to see your partners of the thin rains/ Usual suspects that’ll spawn fatter rains. Why have I been sent to this world?/ When will I live my truth?”

Mchunu says, “Pleiades: Isilimela is the coiled grass rope, doctored with African people’s hairs and body-dirt, herbs and animal fats, oaths and sacrifices to creation, a winding path of time, a staircase and anchor, the umbilical cord from our blue planet to the cosmos.”

The poet deftly fulfills the herculean task of crafting borderless imaginaries. He is a world writer, and endeavours to speak to the anxieties of us all, no matter our geographical or national locations. He finds xenophobia disgusting, and is at ease with his Africanness. “Lend me your pan-languages’ wings to soar above the boundaries of xenophobia, of shame/ I want to bond like Nyagathanga, the bird that chirped, beckoned the daughters of Mumbi …” In these lines in MuGikuyu, a poem in the book, Mchunu pays tribute to a dear friend, the Kenyan activist-scholar, and renowned Gikuyu-English translator Wangui wa Goro, who has translated, among others, Ngũgĩ wa Thiongo’s works.

In the first of two prefaces in the book, Wa Goro reciprocates the friendship. “Vusi reflects the best of muses before him, treading carefully in their footsteps with his own, dancing here, hopping there, sidestepping there, leaping now, ducking again, matching them now, surpassing them then, slowing down and walking slowly, contemplatively alongside, behind them and in front of them.”

South African literary historian and mentor Ntongela Masilela says, Pleiades: Isilimela “engages the poetic musicality” of Mazisi Kunene, and many influences from the world’s indigenous cultures such as the Maori, the Maya and Chokwe. Once a first-class mathematics student at school, the poet dishes a forceful rendition of poetry as enticing predicate calculus of the imagination. “Alaa of the yellow sun, of laundry white gowns bellowing from forgotten Nubia/ Your mehdi maps on your hands ochre-red, nay, blue of the Omdurhman Nile …” The poet asks to be given “the harmony, lyrics of thunder from Keri Nyaga,” pleading, “the coat of the Mau Mau is heavy.”

In his paean to the historically Indian residential areas of Wiggins Road and Greenwood Park in Durban, titled Putu and Roti, Mchunu breathes vitality into his Black Consciousness-influenced embrace of South African identity. “… thread of my unfulfilled life/ again we pierce these cycles of trembling fingers, of vanishing sands of the sea kissed by lips mumbling faint meditations/ beseeching hands holding sceptres of Hanuman/ naked toes entwined on verdant silk trees clapping aside winds from our ashram/ om om om is the echo, is my mantra of sorrow as I kneel warmed by the light of Deepavali …”

The imagery becomes more magisterial as the poem progresses: “i ask you, master chameleon, magician of colours/ will you lend me your rotating eye of the gods/ perhaps flirting eyes of Bharata or the spin of Shembe/ please, give me the stone with chalk lines/ i beg you, may i spit on the stone of Isivivane.”

The dancing poet celebrates African spirituality in an expansive decolonial rendering of bodily memory and non-binary modes of sexual and sensual expression. He dedicates Nobantu, Princess of Kathorus, to the late Nobantu Prudence Mabele, “a pioneering activist of both the HIV-Aids campaigns and the LGBTQI community.” The writing is warm, delicate and delightfully moving. “Till today I fail to wipe off this henna-ochre drip veiling your naughty face/ I can’t find the suitcase with the baby’s clothes, she who vanished as a clot/ Where is the Kleenex to wipe this bitter chapter from your book of sacrifice …”

Finally, Pleiades: Isilimela triumphs as a bold self-redemption song; a poet rising and gesturing towards uncertain horizons, holding up the sun for light and the eventual demise of doom. “To return from separation is to walk hot coals without flinching/ Behind this veiled fog of spiritual secrets passed around, is the laughter of cancer/ Impaled by time. Elevated point in a hill of the jackal. Who knows the ladder of escape?/ Four full seasons of my tongue-speech silenced. Four full seasons, my mind’s been flying./ When the tempers turn orange like the setting sun, I’ll respect the mother of the house.”

Sandile Ngidi is a poet, art critic, literary translator, journalist and playwright. He lives at Amahlongwa, south of Durban, and writes in Zulu and English. Follow him on Twitter at @Mahlephula.