Recreating memory: Dancers, 1967. (George Hallett)

Anyone who met George Hallett, the South African photographer who passed away on July 1, at the age of 77, knows he was a born performer and raconteur, who relished the spotlight at any gathering.

Yet, he was also a trickster figure — a chameleon who knew how to blend in with the background, and observe his photographic subjects’ burdens and most vulnerable states. Hallett’s iconic portraits reveal his shaman’s ability — his ceremonial performances with the camera that created openings into his subjects, especially those who had a lot to hide.

One would not necessarily realise that the slim, lanky man with a small camera, standing unobtrusively in a crowd, had taken photographs that broke through the reserve of seasoned charmers and politicians — including Nelson Mandela — and those, like Eugene de Kock, who had been responsible for the torture and deaths of hundreds, if not thousands, of South Africans who fought for freedom.

Hallett was notoriously economical with his film — times were tough, and film expensive — taking only one or two frames. Yet each portrait that Hallett took is extraordinary — be they of those history has now marked as villain or hero; or the countless South African exiles in Europe with whom he forged close bonds, and whose loneliness, hardships and pain were invisible to a larger public.

Perhaps, as a man who used performance and a loud persona to mask his own difficult experiences of exclusion, and maintained the effects of that damage behind tall tales of grand exploits, he knew how to read beyond what others, too, projected onto the screen. He understood how to look for the tucked-away spaces that were the sources of both light and dark.

Hallett was born on December 30, 1942, in Cape Town’s District Six. He grew up with his grandparents in Hout Bay Village — a small fishing community about 30 minutes south of Cape Town. Nearby lived his uncle and aunt, who had a library full of magazines and books that George was free to pore over — this was his first introduction to literature and art, in which he found solace, inspiration and escape.

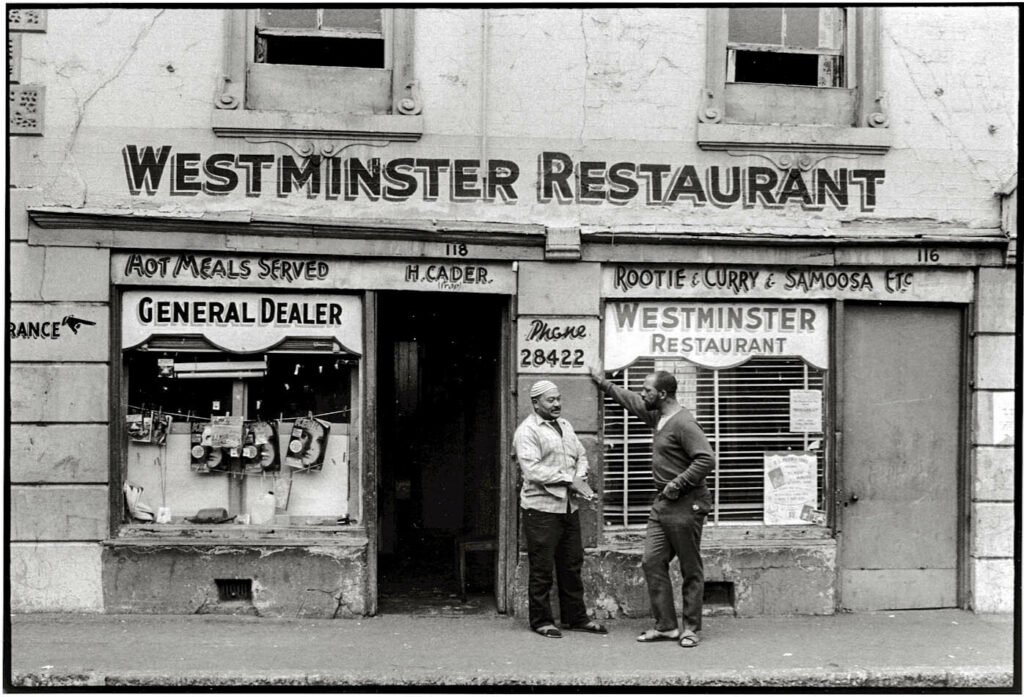

Westminster Restaurant, District Six, 1968

Westminster Restaurant, District Six, 1968 Shoe Shine Fantasy, 1983

Shoe Shine Fantasy, 1983 Dancers, 1967

Dancers, 1967

He also speaks about the thrill of going to the Saturday movie nights organised and shown at his school hall — including many black and white films from the United States. His friends focused their attention on the plot, action and favourite actors. But he was interested in the mechanics of making the film. Although he had no idea that “the camera was … on wheels and was moving on rails”, he situated himself as the mechanism that directed viewers’ eyes. “I became the camera,” he told Paul Weinberg, in a 2007 interview towards the exhibition and book project Then and Now.

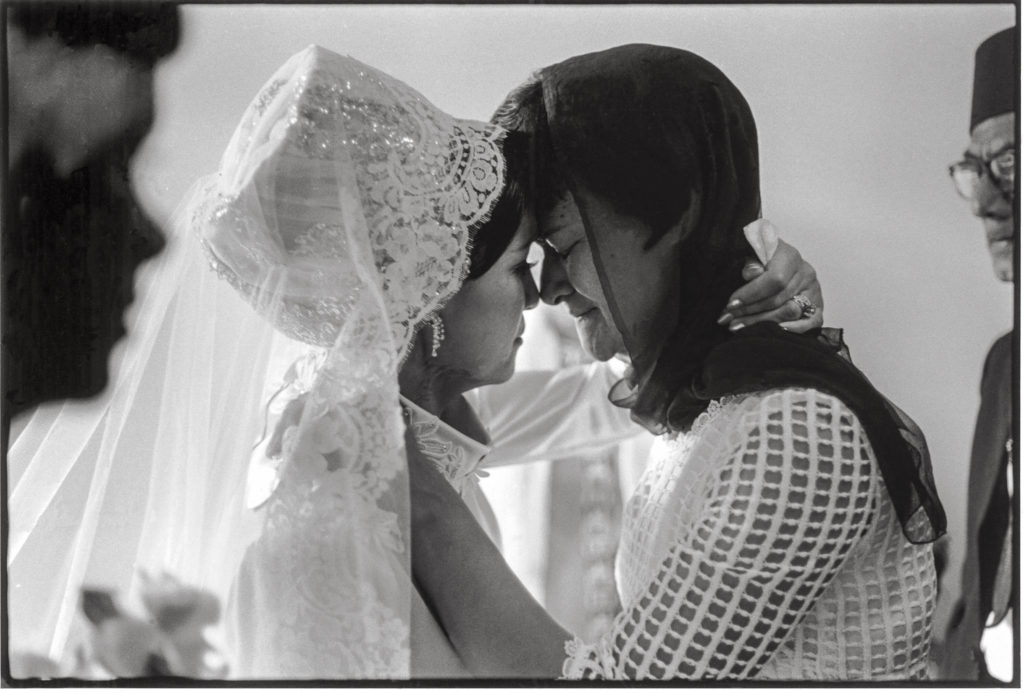

He later left to live with his mother in Athlone, an area outside Cape Town designated for the city’s forcibly removed “coloured” population. In his interview with Weinberg, Hallett recounts how he first began his career as a portraitist. A friend of his worked at Mr Halim’s photography studio — Palm Tree studios — which specialised in portraits, weddings, ID photographs and the like. Every time his friend showed Hallett his work, Hallett was critical of it; he could see that overusing the flash interfered with the portrait, or that the angle of the photograph could be done differently. Irritated, Hallett’s friend challenged him: “If you know so much about photography why the fuck don’t you take pictures?” Until then, the idea of being a photographer had never occurred to him.

Because he had no money to buy a camera, Hallett recalls, he went to Mr Halim’s studio on Hanover Street in District Six, and asked to work for him. He was given a Japanese Rangefinder camera, and unceremoniously told to “go and photograph people in the streets, forty cents a pop”. Mr Halim also told Hallett to “put [his subjects] in the sun”, and not to change the F-stop or the aperture; to leave “the speed just … as it is.”

It was an encounter with a gangster — who sat next to Hallett in a pub, smoke curling up from a cigarette, demanding a photo — that pushed the photographer to explore the settings of his camera. The photo soon landed him a steady skollie clientele, who all “wanted pictures with smoke in their faces, each pleading, ‘Dit lyk soos Humphrey Bogart, man, broer’!”

But Hallett’s most influential educators were not solely the streets: his English teacher, the novelist Richard Rive, introduced him to a larger variety of literature and a circle of writers and artists, including James Matthews and Peter Clarke. It was they who persuaded him to photograph his old birthplace, District Six, after it was declared a whites-only area in 1966, under the Group Areas Acts.

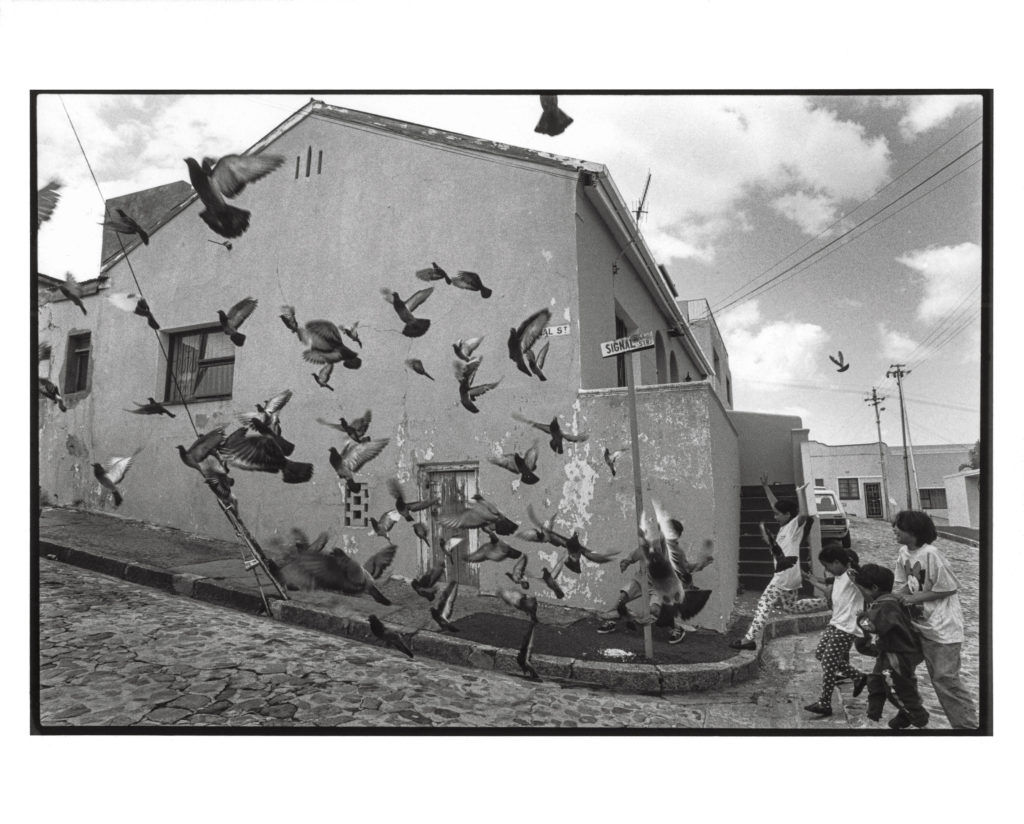

Hallett took his camera to District Six every Saturday, and photographed the ordinary and the unremarkable: everyday scenes, devoid of romanticism or pity. Today, his images remain essential for recreating a shared identity and memory for descendants of those forcibly removed from District Six.

I first met Hallett was when he was invited by Chimurenga to give a talk at the Cape Town Library. There, he spoke about his work as a book cover designer for the Heinemann African Writers Series (AWS). At first, he was formal, but, as he became more comfortable with the audience, he stepped into the role of raconteur-uncle, relishing the laughter of his audience of youngsters, eager to hear the photographer’s exploits.

Hallett recounted what it was like when he arrived in London in 1970 — having found South Africa “too much and not enough”, as he recounted to photography scholar and historian, John Edwin Mason, in an interview published in Social Dynamics: A Journal of African Studies in 2014. There were many ANC exiles in London — including Alex La Guma, Pallo Jordan, Dudu Pukwana and Dumile Feni, among others, Hallett told our small group. He felt at home among them, but needed work.

South Africans in Exile

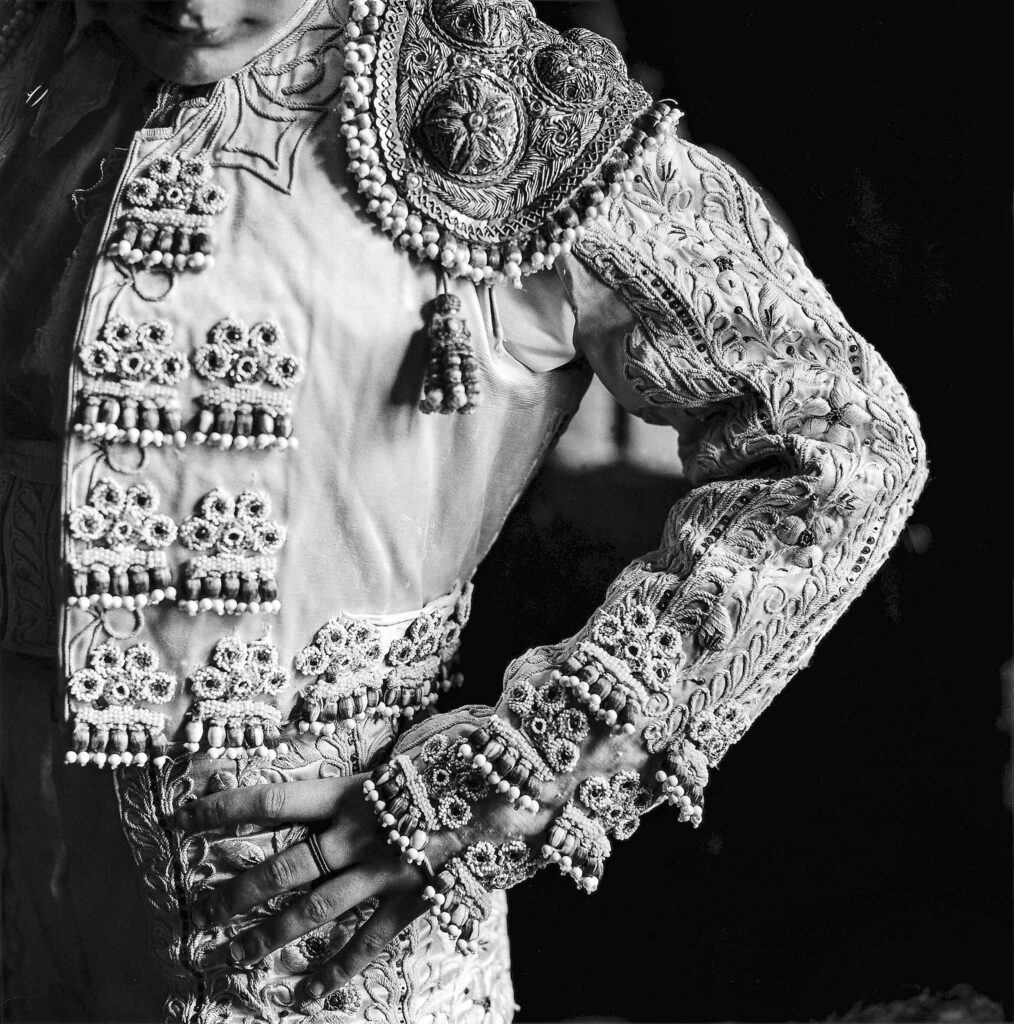

South Africans in Exile Woman Matador

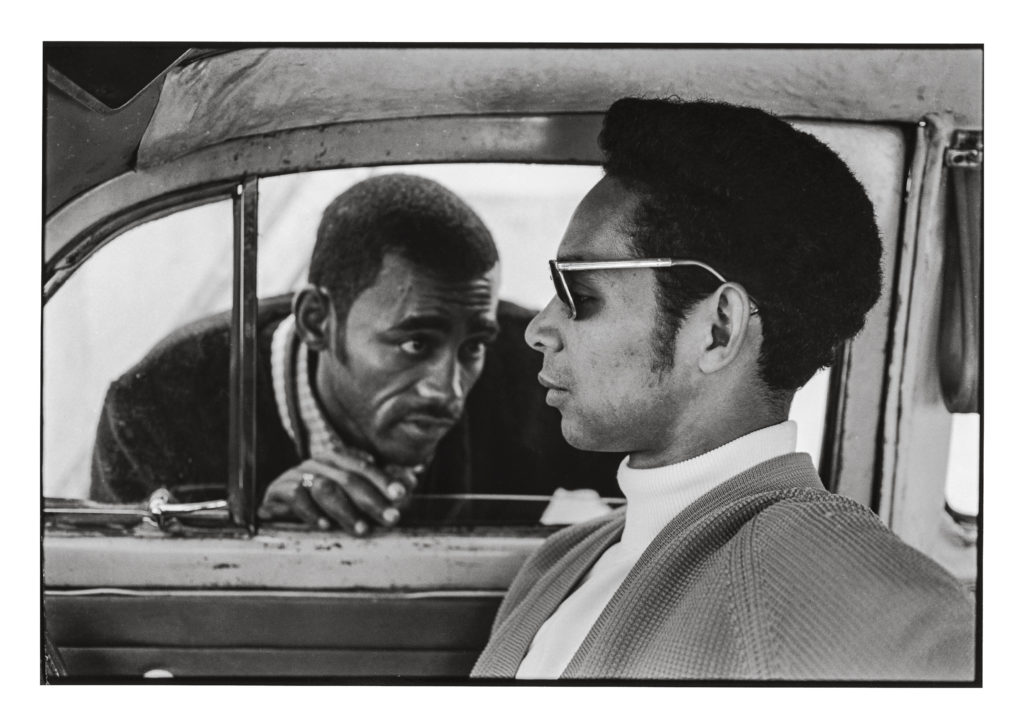

Woman Matador Pleading with Debt Collector, 1968

Pleading with Debt Collector, 1968

He took his portfolio around to press offices, and was hired as a photographer for the Times Higher Education Supplement. Isaiah Stein, a more established exile, introduced Hallett to James Currey, who was the editor of the Heinemann African Writers Series. Currey invited Hallett to lunch. He was thrilled and nervous — he’d never before had lunch with someone of Currey’s professional stature. But he had a great time; there was “a lot of beer and cottage pie, all very British.”

Currey asked Hallett if he had experience designing book covers. “Of course, I lied and said ‘yes, but I can’t show you [samples] … because I couldn’t bring [them] with me when I left South Africa’.” During that boozy lunch, Hallett was charged with designing the cover for Tongue of the Dumb (1971), by Zambian writer Dominic Mulaisho. He used collage techniques to fashion a cover that sported an African mask — “There was no photoshop those days” — and “Bob’s your uncle! I delivered a cover the next day.” For the next 12 years, he produced book covers for the series.

Hallett’s work for Heinemann took him to African writers’ conferences in Berlin, Frankfurt, and Paris, where he became comfortable hanging out with writers — and musicians, painters and poets.

Hallett downplayed the artistry of the covers he designed, but Josh MacPhee notes, in Judged by Its Covers: Looking back at the design of the African Writers Series, that Hallett brought “a sea change to the overall aesthetic of the AWS … Under Currey, photography dominated the AWS covers in a wide range of uses, with Hallett and others moving from powerful arranged scenes (see the cover of DM Zwelonke’s Robben Island) and photomontage (Kofi Awoonor’s This Earth, My Brother…) to abstraction (AW Kayper-Mensah’s The Drummer in Our Time).”

He photographed many authors, and sometimes these images were used as inset images on back covers, which, according to MacPhee, “became a powerful statement in and of themselves, [redefining] diversity on bookshelves across the English-speaking world”. Hallett’s connections with writers also led to a rich collection of portraits, which he later published in Portraits of African Writers (2006).

Birds in Signal Street, 1996.

Birds in Signal Street, 1996.

Hallett lived as an itinerant exile for 24 years. In 1974, he moved to France. As he recounted to Mason, he decided to leave London after an inspector at Scotland Yard phoned him, accusing him of being a part of a terrorist organisation that was planning to kill South African spies. He lived in a small village, Boule d’Amont, near Perpignan, with his partner of many years, Lilli. His daughter, Mymoena, was born on the farm — Mas Domingo — where they lived.

Mymoena remembers many South African exiles came through, and George, whom she calls “Papa G”, made great, performative feats of cooking, preparing feasts of curries and tandoori. For Mymoena, laughter, a little bit of Papa G’s chaos, and photography surrounded her life. Her mother photographed, too, and many of the youngsters around them were, inspired and — unintentionally, perhaps — mentored by her father.

Hallett began making brief returns to South Africa — first, between 1980 and 1981, when he worked in the newly independent Zimbabwe teaching photojournalism — as a way of being closer to his ailing father, and to be present at his father’s eventual death. In 1990, he was commissioned by a news agency in France to photograph the violence stirred up by Mangosuthu Buthelezi and the Inkatha Freedom Party, using well-trained, armed militias. Hallett found it unbearable to photograph this level of violence day to day, and returned to France.

But then he had a prophetic dream. In a 2012 email, he told me: “I had a dream in Paris in early 1994 that I was going to meet Mandela and have lunch with him. The strange thing about the dream was that we were all sitting on chairs that were balanced precariously on the hind legs. When I consulted a dream interpreter in Paris at the time, she told me that I will be meeting Madiba and the reason that the chairs were so precariously balanced on their hind legs was because of the unsteady state of the nation caused by third-force violence. Three weeks later Pallo Jordan [at the time, a key advisor to Mandela; and later elected as MP and the minister of communications, telecommunications and postal services] called me to [ask me] to come and photograph the election process for the ANC. [He said] that I must make my way to [Johannesburg].”

Hallett left for Johannesburg soon after, to take his position as the official photographer of the ANC, commissioned to document Mandela, the electoral process and, eventually, the first democratic government. He got to have that predestined lunch with Mandela, just as his dream had foretold. And just as his dream interpreter had announced, there were shadowy forces conspiring to use violence to roadblock Mandela from fulfilling his destiny.

The Wedding (George Hallett)

The Wedding (George Hallett)

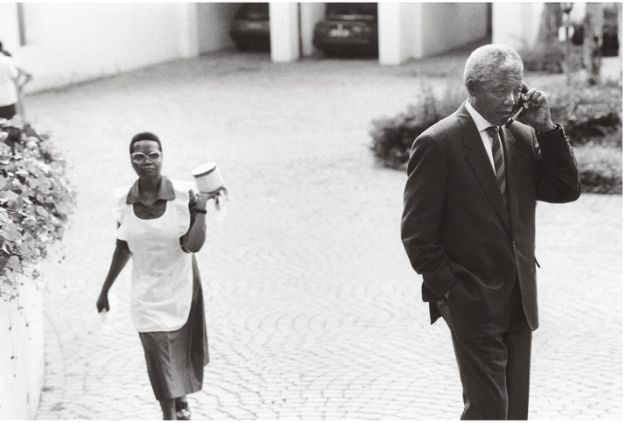

Hallett’s images — under the auspices of the ANC’s direction — filled the empty image spaces created by a 27-year ban on Mandela’s image. Although much of the iconography around Mandela reduced his visual biography to hagiography — manufacturing Mandela into a smiling, unidimensional commodity in the global marketplace, “beguil[ing] the outside world into trumpeting the ‘miracle’ of the South African transition”, as Adam Habib contends (in Myth of the Rainbow Nation, 1996) — Hallett’s body of work during this period presents a multifaceted figure, a complex nation and a fluid, amorphous political process that had unclear outcomes.

Although it is the ANC’s “royalty” he was commissioned to photograph, Hallett’s work during this period and others often focuses on domestic workers. In First Encounter, Johannesburg, 1994, three women — two of them wearing the iconic uniforms of “tea ladies”, and, in many ways, figures as iconic as Mandela in apartheid history — run open-armed towards a receptive, welcoming Mandela. His face is not visible to the photograph’s audience: we only recognise him from his height, slim physique, the greying hair, the impeccable — if loose-fitting — dark suit. The women, their joy so nakedly expressed, are the public who waited decades for the promise of liberation — an impossibility now embodied as possibility by the stately man now in front of them.

Hallett’s memory of this moment characterises his deft hand as a photographer: “That picture with the women running towards Mandela, which I call ‘First Encounter’ — this was the first time they had actually seen him close up. And it was an incredible experience, because for the first time I saw the whole country, and the joy and the hope that people had.”

Hallett’s photographs were later published in a book, titled Images of Change, by Nolwazi Educational Publishers in Braamfontein, Johannesburg, under the auspices of the ANC’s department of information and publicity. The book appeared in landscape format, with 140 pages of captioned, black and white photographs, and an introduction by Pallo Jordan. On the cover of the book is a photograph of Mandela, deep in conversation on a cellphone — his face turned away from the camera — as an aproned woman, instantly recognisable in the landscape of domestic labour in South Africa, walks past him nonchalantly on her way to one of her many daily tasks: to put a full toilet roll in a bathroom.

Mandela speaking on a cellphone with then president FW de Klerk discussing the violence in the country just before the elections, Johannesburg, 1994. (Photo: George Hallett)

Mandela speaking on a cellphone with then president FW de Klerk discussing the violence in the country just before the elections, Johannesburg, 1994. (Photo: George Hallett)

In the latter part of the 1990s, Hallett was tasked with being the official photographer of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in 1997. The intensity of this work took a toll on him, just as it did others who worked with the commission. He would return home, shattered, hoping to find some relief, remembers Rashid Lombard, fellow photographer, director of the Cape Town International Jazz Festival and Hallett’s caretaker during the final years of his life.

“I saw the dark side of Hallett while he was documenting the TRC and especially during the session with former Vlakplaas commander Eugene de Kock [who was] nicknamed “Prime Evil” by the press. I spent a few nights with George listening to loud jazz and lots to drink to calm his anger. I understood the feelings. Music was [our] therapy. Yet he went ahead and captured the most sensitive portrait of Eugene de Kock and Jann Turner, daughter of activist Rick Turner, who was assassinated by de Kock’s hit-squad.”

Captain Jeff Benzine, a former Special Branch detective, demonstrates his ‘wet bag’ torture method to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Cape Town, Western Cape.

1997

Captain Jeff Benzine, a former Special Branch detective, demonstrates his ‘wet bag’ torture method to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Cape Town, Western Cape.

1997 Hallett is remembered by many people as a mentor who influenced their careers as photographers, curators, and writers. Hallett took his craft very seriously. Lombard remembers, “He shot film, using a rangefinder camera. But you wouldn’t see a light meter anywhere near him because he could read his settings just by looking at the light. Sometimes I thought he smelt the light settings.” Christine Eyene, a curator and photographer based in France, cites Hallett as especially significant to her life and work. Others have anecdotes that reveal Hallett’s characteristic no-nonsense style. The journalist Yazeed Kamaldien recalls how, during an interview, Hallett informed “a security guard at the Cape Town International Convention Centre not to tell him that he can’t take photos because this wasn’t apartheid”. Many more remember how he generously housed them in London and Paris while in exile, the meals he cooked and shared, and how he took their portrait, so that they could send a photo to their families at Christmas time.

It is also important to say, at this point in our history, when we are reckoning with the multitude of ways in which misogyny and violence towards women have derailed their careers — or at least robbed them of professional opportunities — that Hallett did not always behave ethically towards those who approached him as a mentor, or for other professional reasons.

I, too, have an experience that speaks to the ways Hallett’s unwanted physical advances were deeply uncomfortable, and created a great deal of dissonance. At the time, I was just finding my way as a scholar and writer. I stepped back, and did not publish the material in the interviews on which I had spent days, and many more hours transcribing. Male colleagues who later interviewed him produced brilliant writing on Hallett’s work. I appreciate that work, without reservation.

I am able, today, to write respectfully of Hallett. Perhaps it is because I had a strong sense of respectful boundaries, and I was already employed as an academic. I know that others may not have had the choices I had. It still rankles that a man accosted me, physically, in the presence of two women, who did nothing. One blamed me for not being “kind” to a man who “only liked” me. Looking back, this is a conversation not just about one person’s conduct, but a far more difficult and involved reckoning that those of us in the arts must face.

In 2014, the Iziko South African National Gallery organised a retrospective of Hallett’s work, titled A Nomad’s Harvest. The exhibition showed the remarkable breadth of his work. It included photographs of District Six, images of his life and those he encountered in France and England — the down-and-out and ordinary figures with whom he’d spent his life — his famous portraits of writers and artists. Each section of the gallery was a sensitive volume, containing several lifetimes’ worth of stories. But it was Hallett’s iconic work after the ANC and Nelson Mandela’s road to victory in 1994, and images from the TRC, that stole the show.

In the photograph of Jann Turner, daughter of the dissident academic Rick Turner, she is pictured looking down on the seated figure of Eugene de Kock. Turner’s father was fatally shot, through a window of his home in a suburb of Durban, and died in her arms shortly after midnight, in January 1978. She was 13 years old. At the time, police turned up no clues. But the TRC hearings determined, after an “examination of the police investigation into Turner’s death, as well as new information which surfaced during the commission’s investigations … that the police themselves suspected the involvement of the state apparatus” — that is, the police knew that the Bureau of State Security (BOSS), was responsible for Turner’s death.

For that reason, the police obstructed the investigation. Eugene de Kock — although he had been the Commander of Vlakplaas, a secret location of torture — always claimed that he had solely carried out his superiors’ orders; in Turner’s case, he said that one of his informants had told him that a BOSS operative, Martin Dolinchek, had killed Turner and that Dolinchek’s brother-in-law had driven the getaway vehicle.

Journalist Jann Turner with former police colonel and assassin, Eugene de Kock, at the Truth and Reconciliation Headquarters, Cape Town, Western Cape.

1997

Journalist Jann Turner with former police colonel and assassin, Eugene de Kock, at the Truth and Reconciliation Headquarters, Cape Town, Western Cape.

1997In Hallett’s photograph of Turner and de Kock, Jann Turner, then in her early thirties, looks at de Kock askance. Neither truth nor reconciliation is present in that room. Turner’s set mouth, her downturned eyes, are directed at de Kock, who continues to evade inquiry by facing the camera. His eyes are obscured behind large, bottle-bottom thick eyeglasses. But Turner’s demeanour also tells us that she no longer depends on or awaits release through any utterance de Kock makes.

Hallett leaves us with many loose ends — unsettled. He also leaves an enormous gallery of photographic work. It will be up to those who are now responsible for his archive to treat it with honour, and to make sure that the history he documented — often at great psychological cost — is available to all.

Go well, George Hallett.