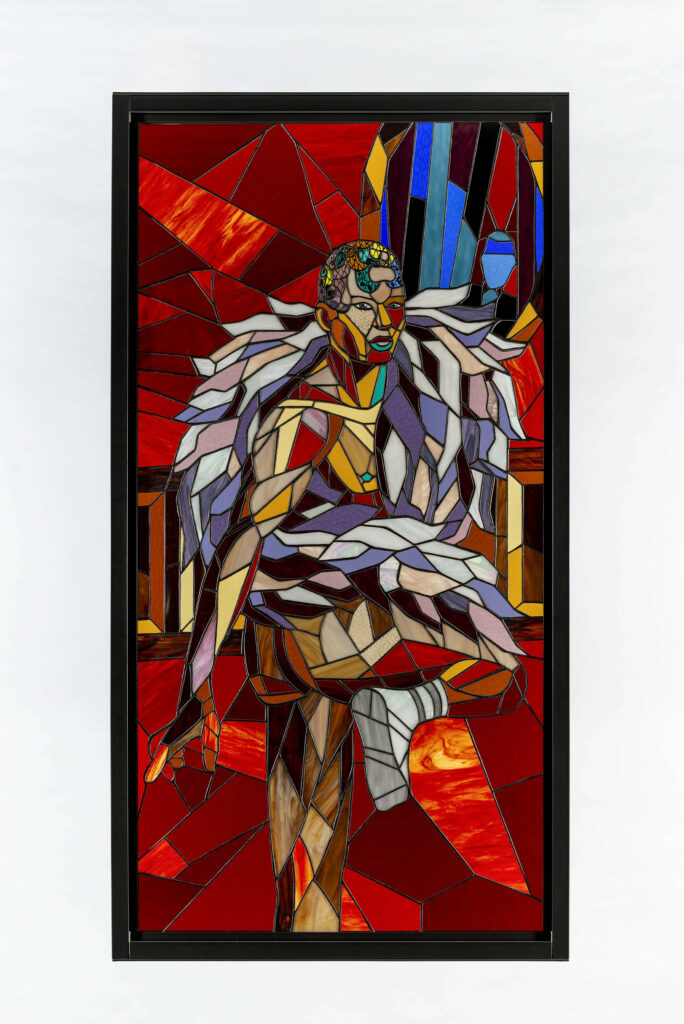

uNobantu noMajola, in which protagonist Nomalizo Khwezi assumes the form of literary character Thembeka kaKhalipha, as depicted in a Lovedale Press classic, AC Jordan’s 1940 novel Ingqumbo yemiNyanya (Athi-Patra Ruga)

Consisting of tapestries and stained-glass works, Interior/Exterior/ Dramatis Personae

represents artist and performer Athi-Patra Ruga’s deepening proficiency with stained glass, which is a relatively new medium in his oeuvre.

The exhibition also sees him enriching the web of stories that animate the internal lives of the characters who either emerge or reappear in the show, from a pantheon constructed from multiple worlds, including “amabali, …gossip, …pop culture, …religion, …resistance and the mannerisms of black women”.

In this interview, he talks about how cataclysmic events in South Africa have shaped his artistry, and deepened his explorations of utopia. He also lets us in on how the properties of stained glass serve his storytelling needs.

Kwanele Sosibo: With your new work, it seems there is even more of an investment into the backstories of the characters, precisely because this utopia you have named Azania seems to become even more elusive with time. This might be a lofty suggestion, but it did come to mind that the stories become a sort of protective armour that cloaks the characters and those experiencing the work.

Athi-Patra Ruga: It’s one that’s welcome. From the pantheon or even the story world of Azania that I have been trying to do, we do note that Azania flies in the face of the Azania that we have either been spoonfed, or the one that we are supposed to measure our ideals against as a nation state.

I think with [the character] uNomalizo Khwezi and The Lunar Songbook [a collection of works informed by, among other things, Southern African astronomy], I have got this obsession or this wonderment that — I don’t know, may be a humanist thing in me — but I’m interested in creating a work that is an encyclopaedia and not just for entertainment. It needs to contain so much institutional knowledge. It needs to contain a lot of things to bite on for this lifetime and for a longer stretch of time. The clash between the archival Azania and the futuristic visual world that I am creating — that clash is where the magic of the exhibition is.

All my characters have a backstory from the beginning. In 2008 I did Beiruth, who was an amalgamation of, yet again, nationalism, and a way of bearing witness to the xenophobic and the miniskirt attacks that happened in Noord [taxi rank]. But with Nomalizo, the character is not fantastical but figurative. So that story then becomes an autobiography for me and for everyone else to judge. uNomalizo has something that is much wider than the rest of the characters.

The stained glass is apt in representing the lush materiality of your work. I know you began working with the material in 2013. But in your journey with it, what have you discovered about the unexpected things it can do to translate your ideas?

When I started with it in 2013, it was a means to an end. I wasn’t so invested in it as a craftsman. There is an element of craftsmanship in all that I do, whether it’s from costume to tapestry to the tactile sculptures.

In 2013, I was using it to parody the nationalistic architecture. That is why I made a parody of a coat of arms out of it. I achieved that goal and moved on. I stepped away from it as well because there is that intimidation when you are starting out with mastering a craft or method.

I then started being fascinated with it — I think that had to do with the colour therapy of The Future White Women of Azania as it unfolded and also the lightwork that is in the sculptural works. My film work is also very much about colour: lighting and strobe lighting — that bombardment or clusterfuck has always been there. But this time I wanted it to further this idea of memorialising. I did it through tapestry — a very medieval thing. I did it through large-scale sculpture, which was tactile. I did one of Simon Nkoli. I did one of Feral Benga.

When I was doing a show in Somerset House in 2018 and one at the Hayward Gallery in 2019, I began working with stained glass again and now I am invested in the discipline. The first fruition of that discipline becomes this suite that you see.

I am using stained glass to institutionalise people, entities, but not in the usual way of institutionalising greater men of lesser deeds, but people from my community, which is deliberately black, deliberately queer and deliberately femme.

A Sight/Site for Contemplation pays tribute to the largely forgotten legacy of Francois “Feral” Benga, a Senegalese cabaret dancer who often performed at the Folies Bergère in Paris alongside Josephine Baker in the 1920’s. (Athi-Patra Ruga)

A Sight/Site for Contemplation pays tribute to the largely forgotten legacy of Francois “Feral” Benga, a Senegalese cabaret dancer who often performed at the Folies Bergère in Paris alongside Josephine Baker in the 1920’s. (Athi-Patra Ruga)

What has been your journey to mastery of the medium? Do you take it from the beginning of the idea to the end of the production process, or are you collaborating with people with a longer history of working with glass?

The nature of my studio is that of collaboration and skills transfer. That’s at the core of why I wake up every day to be an artist. With tapestry, you need to collaborate; with video art, with film, with performance and stage works, you are not an island. With stained glass, I have taken on a mentor, Colleen Peacock, who has been teaching me for the last couple of years. I paint on the glass, I cut it, I choose the textures, which are quite leftfield — there are various densities that actually go against the physics of traditional stained-glass making.

We both work on the tapestry, but the designs are from me — I choose everything.

In one of the videos promoting the show, you read a text that includes the line: “When you cut the glass’s throat, it cuts back, it doesn’t bleed.” It’s an interesting quote on the tactility of the material, but also speaks to this sense of authority glass carries. What is the source of the text and how does it speak to glass as this conduit for your ideas?

That text is from Saint James Yako, who was a poet in the early 20th century in the Eastern Cape, around Alice. So most of his poems were published by the Lovedale Press [which is referenced throughout the work]. That one was called iGlasi. A very naive title, but I love how it goes to actually just say, “Xa uyisikayo nawe iyakusika.” That’s the strength and the fragility of the material. For me, what sticks out in how I presented the material is in how it floats. That poem relates to that.

Swazi Youth After is a continuation of a 20-year long conversation with Irma Stern that also references queer subcultures (Athi-Patra Ruga)

Swazi Youth After is a continuation of a 20-year long conversation with Irma Stern that also references queer subcultures (Athi-Patra Ruga)

Irma Stern is a name that comes up in discussions on your work. The exhibition text speaks of this as “a sustained conversation”, with some of the work here, like Swazi Youth After, referencing her work while “subverting” the gaze. Can you talk about the scope of you speaking back to her work, because I understand it goes back quite a long way?

My relationship with Irma Stern begins in the late nineties when I steal a book from my art school in East London. It’s had such an influence on me as a colourist. Later on, as I move to Johannesburg and study fashion and hang around artists who are critical thinkers, I get to learn about the ethnographic nature [of her work] and her patronising depictions of black people. It awakened many questions that I wanted to then pose to her.

I’ve been having this conversation in my head with her for more than 20 years. It’s about who takes precedence in portraiture? Is it the person who is sitting? Is it the artist or the artist’s technique? Is it the viewer? I’m interested in this triangle of power. So the conversation with her becomes this conversation I’m having about myself, as someone who documents people — especially people who are marginalised. It becomes a very big question around my complicity in capturing images and also the fact that she did work at omitting some things.

One of my first works I did of Irma Stern was a rendition of the Wathusi Queen. To start with, you can’t say “Wathusi” because it is a bastardisation of the Tutsi. In all the time she sat to do this portrait of the Tutsi queen, she doesn’t actually mention her name. So I start doing tapestries where I name, or where I give a little bit of a backstory to the titling, or even giving bones sometimes, because some of the characters look like they are so flimsy they will be blown away by the wind.

Castrato as [the] Revolution continues the artist’s long-standing interest in self-portraiture, this time riffing on castration as erasure and various performance histories (Athi-Patra Ruga)

Castrato as [the] Revolution continues the artist’s long-standing interest in self-portraiture, this time riffing on castration as erasure and various performance histories (Athi-Patra Ruga)

Could you speak about Castrato as [the] Revolution, and self-portraiture in your work in general, as a way of addressing some of these complicities that come up as an image maker?

Self-portraiture is a tool in which I put myself on the chopping block instead of the gaze that is sometimes expected. You’ll see a lot of images of me severing my head, as well. Castrato as [the] Revolution is a self-portrait harking back to a castration by various systems: a homophobic system, an anti-black system, anything. Another form of castration is erasure, depicted here by a scratching out of the face, a silhouetting of the penis; also harking back to the castrato and the history of drag. I do like dropping things in there that will help people find out more about other gay history, art history or performance history.

What has being based outside the city meant for you creatively?

Of course, I have always drawn but I am focusing very much on draughtsmanship in Hogsback. Johannesburg in the beginning and, currently, Cape Town offer me a performative vibe and we can’t perform now. I need to focus on another medium. That is just the reality. I am writing a lot of performances and drawing storyboards for future film works. I might be shooting, here in Hogsback — a continuation of The Lunar Songbook.

There used to be a fear I had, because it’s something very industry-borne — when you are young and get into a career — people used to speak about the centres of the art world and how you have to be there for things to happen. It’s been a very big fear of mine to take time out and not be in Cape Town or a metropolis. It’s been so amazing to be in a space where I’m not afraid of losing my talent because I’m not in the city.

I’ve written a manuscript for The Lunar Songbook and I’m in the process of making a feature film. Last year my screenplay was taken up by The Realness, a residency offered by Urucu Media. My story coach, Mmabatho Kau, has been helping me to develop it. I also got to go to Locarno, a filmmakers academy, all of which is helping me take the Lunar Songbook from the white cube to the silver screen. This is the encyclopaedia that I’m talking about. Also, there are two books I’ll be releasing in digital form: The Future White Women of Azania and Of Gods, Rainbows and Omissions.

Interior/Exterior / Dramatis Personae: A Saga in Two Parts, runs at What If TheWorld until September 5.