South Africa’s “legalisation” laws ration adult home-growers to four female flowering cannabis plants (Guy Oliver)

At Home with Cannabis

Kelly McQue

(Penguin Random House)

One Saturday in Cape Town Central’s police cells during the early 1990s an alleged diamond smuggler, shoplifter and dagga kop were anticipating the 36 hours to the bail hearings and a clock winding down to the late-night arrivals of the well-soused. The best-dressed man in the room said: “Someday they’ll legalise dagga and not the way hippies like you hope. It’ll be drip-feeding a market from a huge pond.”

Adjusting his cravat while qualifying his innocence, he rose from a stone-cold bench for a prophecy realised nearly three decades later after the Constitutional Court forced the government’s hand to “legalise” cannabis. Citing Italian neo-Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci’s “cultural hegemony” theories and slices of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations free-marketeers’ bible — the smuggler sketched a dagga trade moulded on a cartel’s manipulated scarcity to conjure a high priced gemstone from a common crystal.

South Africa is scheduled to inherit the mantle of the world’s largest regulated marijuana market from Canada on September 18 under a “legalisation” banner — the Orwellian translation for cannabis rationing.

What the new law allows

The post-prohibition cannabis laws allow recreational smokers a gulp of legal air and impose lengthy jail sentences for artisanal medical marijuana producers. The law’s logic hands corporate medicine an uncluttered landscape to monopolise a billion-dollar industry and junk the knowledge store of generations of “illegal” cannabis healers.

The corporate charade peddled is that medical marijuana production is a highly complex laboratory process only accomplished by clinicians in hair nets, white coats, goggles and masks — an illusion realised after slipping the government tens of millions of rands for gardening privileges.

“It’s not difficult to make,” Getafix*, a medical marijuana purveyor for three decades, says. “Medical marijuana is the extract of a plant. There is no mystery to its making.” Wearing a clean shave for a disguise, the retired Cape Peninsula-based science teacher, “illegally” produces and treats an array of illnesses from migraines to cancers and dispenses his homegrown medical marijuana on a break-even budget.

South Africa’s “legalisation” laws ration adult home-growers to four female flowering cannabis plants; the quota is doubled in properties for two or more adults. The rule of thumb for medical marijuana production is a 10:1 reduction of the plant’s female flower. The low cap thwarts legal production in sufficient quantities to treat chronic illness or for other required medical regimes.

The 2020 Cannabis for Private Purposes Bill’s sleight of hand is the low ceiling afforded for home grown, “trafficking” offences for cultivating six female plants or more and jail time ratcheting up to 15 years for an avid horticulturist.

The decarboxylation stage of manufacturing medical marijuana (Guy Oliver)

The decarboxylation stage of manufacturing medical marijuana (Guy Oliver)

The medical marijuana cookbook

Kelly McQue’s At Home with Cannabis is, at face-value, a recipe book for homegrown remedies. It’s a comprehensive guide to manufacturing and administering affordable medical marijuana treatments from acne to soothing nerve pains, through to cancers and insomnia. In its essence, the book is an act of sedition against high-priced corporate medicine enabled by a governing party obsessed with piles of cash and brown paper bags.

“The pharmaceutical companies and government are working together to restrict our access [to cannabis],” McQue says. “It’s malicious compliance” to the 2018 court ruling for marijuana’s legal private use.

“The Constitutional Court did not put limitations on privacy,” she says. “I don’t see how putting these very strict restrictions is going to promote my right to privacy.

“It’s going to allow the police more access to my home,” the KwaZulu-Natal based author says. “They are keeping us in the illegal area.”

The cannabis “legalisation” laws are from the literary traditions of the Covid-19 lockdown authors: byzantine regulations laced with marijuana prejudice from an ageing, analogue mindset coated in monotheism’s righteous lickspittle. In The Beyond Parody Age, the regulations are a souvenir for the times.

Finance Minister Tito Mboweni would face up to four years jail time for a tweeted picture of his backyard weed, which fails to “take reasonable measures to ensure that the cannabis plant is inaccessible to a child”. A spliff at home in the “immediate presence of any non-consenting adult person [wife/husband/domestic worker/mistress/plumber]” risks up to two years incarceration.

‘Vested interests’

It’s more homage to East Germany’s Stasi secret police than a celebration of the Constitution’s human-rights sentiment. The cannabis “legalisation” paints broad legal grey areas codifying police corruption perks offered from the marijuana community and reveals the government’s reluctance to ride a billion-dollar global cannabis wave tailor-made for the country’s climate.

“There are too many vested interests” for it to be legalised without restrictions, Tony Budden, a leading Cape Town cannabis entrepreneur of 25 years, acknowledged in an interview last year.

The post-prohibition cannabis laws allow recreational smokers a gulp of legal air and impose lengthy jail sentences for artisanal medical marijuana producers. (Guy Oliver)

The post-prohibition cannabis laws allow recreational smokers a gulp of legal air and impose lengthy jail sentences for artisanal medical marijuana producers. (Guy Oliver)

Industrial cannabis is a disrupter with few parallels. The petrochemical companies deployed Christianity’s useful idiots to ban a plant their God insisted Moses pack as an essential item for the Exodus — allowing a fledgling synthetic technology to flourish unimpeded by the competition. Wandering the wilderness for more than 80 years, cannabis has lost none of its lustre for disruption.

The government’s legal shackles for a plant recognised as the fourth industrial revolution’s floral component floats the usual decoy of the buzz of a non-addictive substance threatening a “moral order”.

A versatile plant

Cannabis’s existential threat to society’s status quo is much more profound than that. The raw material — which generates an immense, 3m-tall biomass at up to 200 seedlings a square metre, can be harvested within a few months and has negligible traces of any psychoactive compounds — trespasses on many a corporate doorstep’s supply chains.

Cannabis, unbridled of its legal baggage to promote a raw-materials abundance, will flip the plant’s cardinal sin of industrial promiscuity to the entrepreneurs’ advantage. The plant’s versatility allows both low- and hi-tech “beneficiation” to roll out products threatening corporate supply lines: construction, animal feed, textiles, insecticides and cooking oils, are just a short selection of its thousands of industrial applications.

The fate of medical marijuana is the opening skirmish on a contested terrain between cannabis culture and a government’s corporate tryst to throttle an industry not in its image.

“The pharmaceutical companies are very much about one-size-fits-all and extract specific properties from the plant and give it to you in specific doses. It’s a very different model to the more natural approach,” McQue says. She prefaces the book’s medical marijuana production instructions, and processes for a variety of infusions, tinctures and remedies, documenting her successful breast-cancer therapy using the natural medicine.

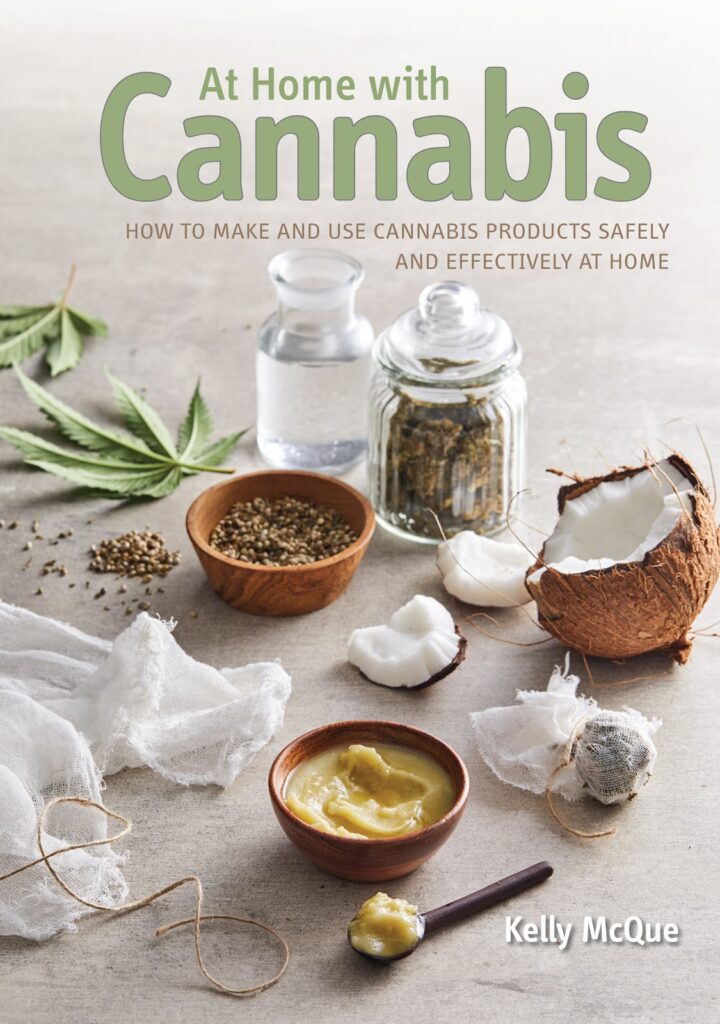

Kelly McQue’s At Home with Cannabis is, at face-value, a recipe book for homegrown remedies. (Penguin Random House)

Kelly McQue’s At Home with Cannabis is, at face-value, a recipe book for homegrown remedies. (Penguin Random House)

Treatments for “extreme nerve damage pain needs higher doses” than “someone needing to sleep better. To limit it at all is to infringe on a person’s right to use cannabis,” McQue says. “We need to be very careful in placing our trust in government regarding cannabis.”

The Canadian model

Canada’s tightly controlled legal marijuana market initially dismissed the sophisticated cannabis underground as a bunch of stoners who would be stoked to buy high-priced, inferior, “legal” dope from state-licensed dispensaries. Cottage industries nurtured within prohibition’s confines exploded on to Canada’s 2018 quasi-legal market to counter the government myth of a regulated market wilting an underground rooted in 1960s anti-Vietnam war activism. The vast array of high quality, low-cost boutique cannabis products available on tap from the “illegal” sector is a regular lament by the corporate competition for bursting the profit bubble promised by trade restraints.

The Canadian blueprint for a regulated cannabis market is South Africa’s template for the post-prohibition era of privileged access for a few to a commodity that grows like a weed. “It’s very clear that government does not wish to work with us [artisanal medical marijuana producers],” McQue says. Expect litigation? “Loads of it.”

*Names have been changed