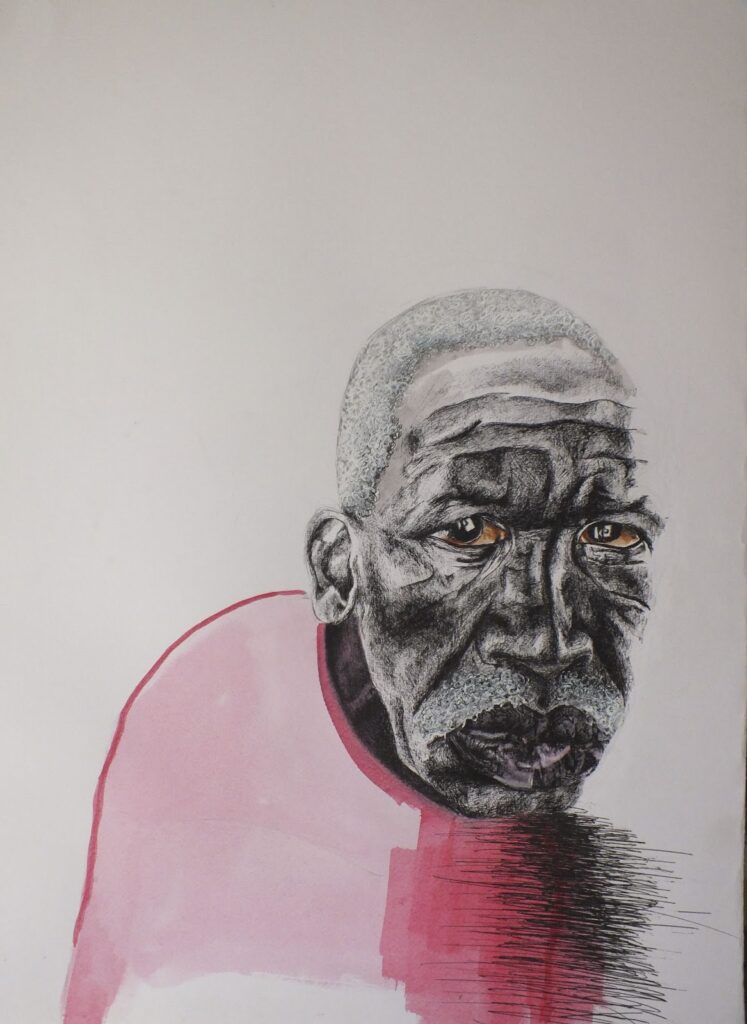

The artist and poet's practices flow into each other in the imagery they evoke. (Detached, Mxolisi Dolla Sapeta)

Mxolisi Dolla Sapeta is perhaps best known for his work as an artist and sculptor. In 2019, he made his literary debut with his first collection of poems, Skeptical Erections, published by Deep South.

Reading Sapeta’s collection makes it quickly apparent that drawing too sharp a distinction between Sapeta’s art and his poetry would miss a rather important point: Skeptical Erections is a canvas and his words his paint.

A recent profile of Sapeta appearing somewhat unexpectedly on the Nando’s website describes him as an artist who “employs colour, form and composition to portray an emotional environment rather than the physical one”. It continues: “[Sapeta’s] work speaks of the alienation and degradation of existence in the impoverished urban townships of South Africa – and the societal ills that congregate around such existence. These complex and brutal circumstances are deliberately reduced, condensed or distorted – brutalised even further – by Sapeta’s expert treatment in acrylics, creating works that confront and unsettle the viewer.

“Narrative is fragmented, characters and objects isolated and stripped down, threatened and overwhelmed by flat backgrounds of vivid colour. His figures are simultaneously heavy and untethered, decontextualised and anonymous – they speak of the human condition rather than the particular human, in service of the artist’s pursuit of prioritising another, abstracted identity, what he describes as ‘an alienated atmospheric character in my work’.”

The Masturbator (Mxolisi Dolla Sapeta)

The Masturbator (Mxolisi Dolla Sapeta)

Such a description remains apt for his poetry too. Upon opening the collection, the reader is confronted with reduction and an instant sense of hopelessness. The first poem, bottom of an envelope, conjures an individual requesting forgiveness for his “apologetic speech and reason” and who, at the poem’s closing, remains “armed with nothingness”. This is a man who personifies the environment of despair in which he lives; the New Brighton township of South Africa’s Eastern Cape. As Robert Berold, writing for Africa in Words in May this year observes, Sapeta has “a deep emotional and physical connection to life in [South Africa’s] Eastern Cape townships 25 years after the end of apartheid”. Sapeta himself, only a few poems into the collection, writes:

I am a talking township

I rise and fall where the township falls

I have a colossal share in its fatherless children

And ownerless dogs in the barking streets.

Between Sapeta and New Brighton, the poems speak of a shared sense of loathing. They depict the widespread unemployment, crime, sexual violence and political corruption that has grown within the township and begun to seemingly contaminate all who live there. Unavoidably, the socio-spatial and the personal have become entangled, which is highlighted by the personification in my town:

I want to lose this disappointed town

With a broken face that stands for everything rotten

A forgery with no soul on its way to oblivion

The brutality of township existence is only enhanced by the sexualised physicality that so often takes centre stage. Frequently it is unnervingly, unashamedly base — for example, the description of “the loud snoring of her pussy/and its endless spout of dead semen”; at others, however, a subtler combination of the physical and spiritual serves to complicate and distort any initial reading of the poet and his relationship with New Brighton. Consider the poem and by all means, where the opening, “your bosom is my heaven and I remain your pilgrim”, gives way to “the murky wetness of your body”.

The poems in Skeptical Erections force overwhelming encounters with a truth laid bare (Deep South)

The poems in Skeptical Erections force overwhelming encounters with a truth laid bare (Deep South)

This description typifies the monsoon of visual imagery that floods the pages of Skeptical Erections. Sapeta’s art uses its colour palette — though at times muted — to “suffocate” his subjects, offering them “nowhere to retreat to”. Similarly, the imagery in his poems forces an overwhelming encounter with the truth laid bare. Individuals are distorted into something hyperreal; Sapeta’s perception of himself and his surroundings taken to extremes: “I am from a violent seed — a legacy of vulgarity”. You cannot but help respect such honesty, a self-assurance that suggests a sense of control at odds with the unsettling and threatening evocations of the past, of the violence and the despair that would otherwise sweep through the page.

The African Books Collective suggests this is a collection in which Sapeta describes the “deception and self-loathing prevalent in the people he encounters in his work, including (or perhaps especially) himself”. I agree that Sapeta implicates himself more than anyone else because in the poet we see is a man who owns his own situation. In doing so, Sapeta maintains agency and prevents any voyeuristic judgement from those who look upon him. This is a realist who accepts the situation of self, community and country as it is.

A painting from Mxolisi Dolla Sapeta’s Fathers’ Day seties

A painting from Mxolisi Dolla Sapeta’s Fathers’ Day seties

There are no grand illusions or announcements of change. The holes within the rhetoric of the new South Africa are also accepted. But that is not all there is. That is not the end. New Brighton and South Africa have changed. Sapeta has too, inextricably bound to them, “taught in your crucifix”. All will continue to change and build anew but, given the current situation, one perhaps must question what the future holds. As the final poem declares:

the light flickers through your mouth

and I realise I am wrestling for life

a frightened fetus at the bottom of your gloom.

Put more simply, the future is one of skeptical erections.

This article was first published in africainwords.com