Jade Palmer examines the gendered expectations of domestic labour and its effect on the interfamilial dynamic in Some time in February.

In a time of intensive self-scrutiny, artists can offer illuminating perspectives on enduring issues. This is powerfully demonstrated by the winners of the Wits Young Artist Award of 2020, an annual competition presented by the visual art department at the University of the Witwatersrand. Curated by artists and Wits faculty members Gabrielle Goliath and Reshma Chhiba, this year’s exhibitions, titled Rudiment and Hope Sub-verse, took place online.

First-prize winner Vick Bester, and merit-award winners Pebofatso Mokoena and Jade Palmer each engage with the particularities of the places where they live (or have lived), with fresh intensity.

The artists ask: When recent history is documented, how can one bridge the distance between the archived and the experienced? When the outside world is violent, to where can one escape? When the division of labour is gendered, how does one resist? These ideas are boldly claimed and wrestled with. Here, the artists carve out new space for their own voices, in which the world of theory and daily experience converge on a personal level.

In Mokoena’s winning submission, Kea hoNkgono leNtatemoholo (I’m Taking a Walk to the Grandparents), 2020, the artist returns to what he has termed, the “height of ethno-tribal, sociopolitical and geo-transportational violence in Thokoza 1993”, which took place when Mokoena was only a few months old. He goes on to describe Thokoza as the “nexus of political, socio-ethnic and psychosocial upheaval.”

‘I wanted to speak in between the corners of the archival text, and the more that went on, the more it felt like a kind of boxing match that happened on paper.’ (Pebofatso Mokoena, Kea hoNkgono leNtatemoholo, 2020)

‘I wanted to speak in between the corners of the archival text, and the more that went on, the more it felt like a kind of boxing match that happened on paper.’ (Pebofatso Mokoena, Kea hoNkgono leNtatemoholo, 2020)

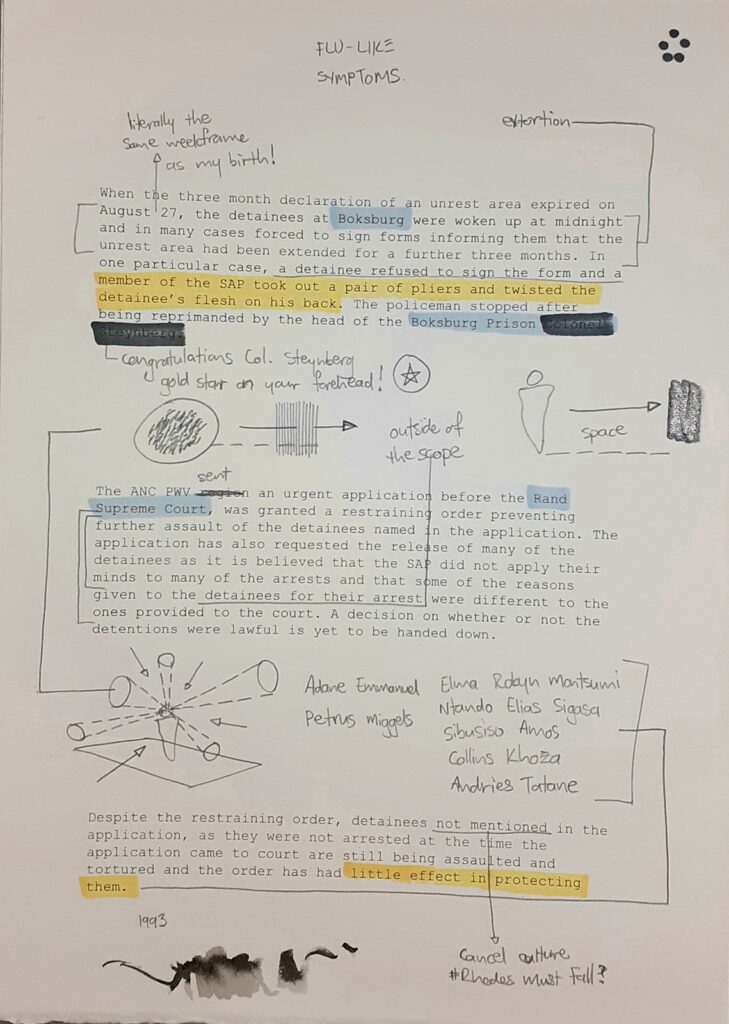

Kea hoNkgono leNtatemoholo (I’m Taking a Walk to the Grandparents) comprises a series of paper-based works, in which Mokoena has taken archival and academic excerpts focused on the violence in 1993 and disrupted these texts with handwritten commentary, mark-making, diagrammatic drawing and reproductions of colour photographs.

The artwork itself functions as a meta-nexus for a multitude of textual references in addition to Mokoena’s interpretations of the text. As the text describes fatalities and the destruction of homes, at times in excruciating detail, Mokoena picks the texts apart — questioning, expanding or redacting.

Recounting the process of creating the work the artist says: “I wanted to speak in between the corners of the archival text, and the more that went on, the more it felt like a kind of boxing match that happened on paper.”

The family left Thokoza when Mokoena was a young boy but, as he describes, they continue to “move in and out of the space constantly.” Reflecting on the enduring effects of 1993’s events on the lives and psyches of those living in the present, Mokoena says that people of his generation continue to battle with the “critical distance to speak about it clearly”.

Echoing this, in his statement on the work, Mokoena describes the “chasm” that existed between his interior life as a child, and his understandings of the events in Thokoza as an adult. Mokoena says, “It was important for me to set up the conversation in that way, because the older I got, [the more] I realised that I needed to bridge these two worlds together. That’s what I wanted the work to become.”

Some time in February, 2020, Jade Palmer’s winning entry, examines the gendered expectations of domestic labour and its effects on the interfamilial dynamic. The subject of the artwork is Palmer’s own family, in which the women in the house carry the primary responsibility of the upkeep of the home.

Using sound and video, in Some time in February (2020), Palmer narrates the domestic activities of the family over a number of days.

Some time in February is part sound and part video work, in which Palmer narrates the domestic activities of the family over a number of days. In part one, through the absence of the visual, the listener is transported into Palmer’s home through sounds of dishes being moved and the chatter of a radio. Palmer explains that by focusing on sound the listener is compelled to “imagine their own space, instead of seeing my own”. The artist’s voice overlays these familiar sounds, describing the day’s housework, which Palmer’s mother begins at about 4am.

Despite the calmness in Palmer’s narration, it is clear that the nature of the work is relentless. There is always something to do, the responsibility of which falls to Palmer and her mother, as the family carries out the unavoidable activities of daily life: eating, washing, moving. The artist deftly analyses the family’s movements and conversations, while emphasising the labour that keeps family life liveable.

In the video portion of the work, Palmer is now seen sitting in the kitchen in stillness. The narration turns to a moment of resistance in which she repeats: “Sometimes I refuse to do certain things, not because I’m unable to, but because I simply don’t want to.” The refrain continues until fatigue sets in. Much like the perpetual cycle of housework, the refusal must be repeated, and thus the work can be reclaimed as a kind of power, not burden.

Although Palmer is deeply critical of the gendered divisions of labour, this self-reflection within the home is complex. The work was realised in the home where the artist continues to live. She pointedly notes: “This is the work, but it is also my reality.”

Vick Bester says the medium of miniature is utopic in its intentions

Vick Bester says the medium of miniature is utopic in its intentions

Bester, too, invites the viewer into the family home, but has opted for an entirely different approach, instead revealing and exposing their most private world to the greater public. Loneliness Secrecy & Making, is a miniature representation of their room, complete with every detail scaled down so minutely that the objects are made precious and dwarfed by their hands. A laptop and embroidery hoop — an artwork within the artwork — sit on the bed. In the corner are propped-up canvasses and rolled-up paper; under the bed, a world of private secrets and pleasures.

Bester began the practice of making miniatures in 2020, while working through the Sara Ahmed text Orientations: Toward a queer phenomenology (2006).

The miniature is utopian in its intentions, and Bester says of the medium: “I started making miniatures as an escape; a fantasy space for the queer body to exist safely.” Their family bedroom operates as holding space for every experience — for heartbreak and despair; a place to make art; and a place to perform their own experiences of gender unquestioned.

For those who are able, home in the time of pandemic has become our whole world, where we work and find time to rest. But what happens when that refuge is disrupted, or has structures of violence embedded within it?

Bester reflects on the bedroom as a site for critical exploration: “People infiltrate that space, sometimes violently, sometimes unexpectedly, and sometimes lovingly.” Although recognising the limitations of access to the digital space, Bester appreciated that the exhibition and the work could be viewed more widely: “It’s important to understand that vulnerability is necessary in these times when that’s all we are: vulnerable.”

When considering the artists’ work as a group, as viewers, we are offered the great privilege of being invited into the intimacy of their spaces. However, through personal digital devices, the online exhibition creates a private viewing experience, which produces an unexpected closeness during such periods of sanctioned isolation. These works, portals into the mind, family home and bedroom, magnify the expansiveness of interior life, so often hidden from others.

To borrow Mokoena’s term, the artists’ work is a nexus of personal reconstruction; a culmination of their pasts and their dreams for the present. Each artist describes a necessity to make work to process that which is personally and socially cataclysmic. The work is also a site in which to celebrate personal and private victories; to acknowledge that which remains unsaid; and to honour the gravitas in the seemingly small or obscure.

The Wits young Artist Award exhibitions Hope sub-Verse and Rudiment will be available to view online until November.

The following WYAA shortlisted artists exhibit alongside the winners: Griffen Alexander, Jordan Cassidy Anthony, Tzung Hui Lauren Lee and Shayna Rosendorff, Shamil Balram, Yakira Gishen, Ayabonga Magwaxaza, Ndabenhle Mthiyane, and Tehillah Snyman.

Selection panel: Ingrid Masondo and Athi-Patra Ruga. Adjudicators: Danni Bowler and Alia Farid.

This article was produced as part of a partnership between the Mail & Guardian and the Goethe-Institut focusing on innovation in various aspects.