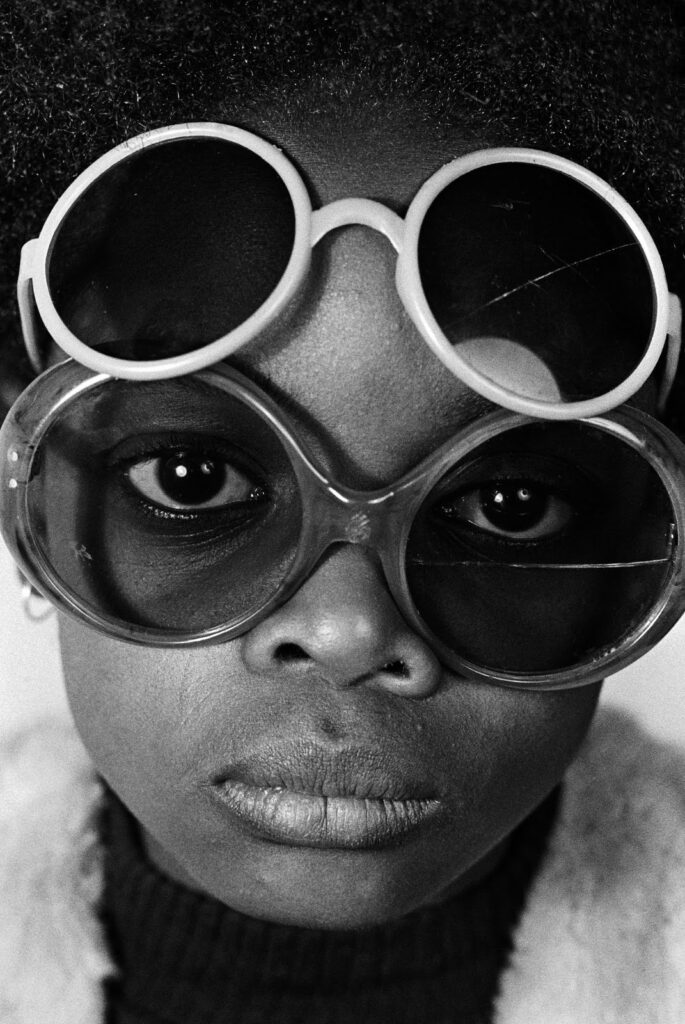

Dignity and Pride, Hackney, London, 1973. (Photo: Dennis Morris)

In 1972, the American singer Johnny Nash, who just died aged 80 on 6 October, went to Britain on tour. Accompanying Nash, whose song I Can See Clearly Now sold a million copies, and reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100, was a struggling, little-known Jamaican band, The Wailers.

The band’s on-and-off sojourn in Britain, and especially the fortunes of a certain Bob Marley — who emerged as the leader of the reconstituted group after the other two musicians, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer, left snowing “Babylon” to go back home to sunny Jamaica — are the subject of the new documentary When Bob Marley Came to Britain.

The BBC film, directed by Stuart Ramsay, is concerned with Marley’s time in the “mother” country which, by most accounts, was initially a difficult one. The band was unknown, and mostly played at schools, university halls and small venues, in front of tiny crowds. It appears that on the tour with Nash, Marley was his accompanist, playing acoustic sets at scores of schools around Britain.

The Wailers’ personal circumstances were not any better: Marley, Tosh and Wailer shared a one-bedroom flat with no kitchen, forcing the Rastafarians to subsist on fish and chips, and vegetarian Indian food.

The inclement weather — rain and snow — contributed to the 1973 tour collapsing and the eventual break-up of the band. The song Concrete Jungle on the album Catch A Fire and its plaintive verse: “No sun will shine in my day today/ The high yellow moon won’t come out to play,” captures some of this gloom.

However, Marley persisted and within a couple of years was a genuine rock star, as proved by the now legendary sold-out 1975 show at the Lyceum, the grand 2 100-seat theatre on the West End, London. That sojourn in Babylon forever changed reggae: bringing it new listeners, including in Africa, and Britain’s own music scene would never be the same.

Count Shelly Sound System, Hackney, London, 1973. (Photo: Dennis Morris)

Count Shelly Sound System, Hackney, London, 1973. (Photo: Dennis Morris)

Reggae and dub sought, and found, a spiritual kinship with British punk rock — the island’s own rebel sonic. The song Punky Reggae Party, in which Marley gives a shoutout to the British bands The Damned, The Clash and The Jam, is an acknowledgement of this relationship: punk rock, as we would say in southern Africa, is reggae’s cousin sister.

Marley’s stay in Britain also changed the fortunes of one particular man, the photographer Dennis Morris.

Sometime in 1973, Morris, then a teenager in his last year of high school, read in a magazine that The Wailers were coming to tour Britain. Instead of going to school, Morris took his camera and waited at the entrance of Speakeasy, a club in London where The Wailers were to hold a gig.

“I was very much into music, and very much into his music, so I decided I wanted to take a picture of him and I didn’t go to school that day,” Morris told me on Zoom from his base in Los Angeles.

The groundbreaking album Catch a Fire had just come out, and Bob Marley’s producer, Chris Blackwell, was trying to promote it to an audience beyond reggae’s traditional listeners. The Speakeasy, on 48 Margaret Road, once host to Pink Floyd, Elton John, The Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix and The Beatles, was a suitable venue.

“When he eventually turned up I asked could I take his picture, and he said, ‘Yeah man, come in.’ So I went in and he was asking me how it was like to be a black man in England. I was asking him what Jamaica was like and he really took to me and he told me about the tour and asked me if I would like to come along. I said yes. So the next morning I didn’t go to school and I packed my bag and went to the hotel and jumped into the van and there is a famous picture of him looking back. He said, ‘Are you ready Dennis?’ and I said, ‘Yes.’ And so the adventure began.”

Bob Marley in The Wailers’ tour van in 1973. Just two years later, he would be heralded as a genuine rock star. (Photo: Dennis Morris)

Bob Marley in The Wailers’ tour van in 1973. Just two years later, he would be heralded as a genuine rock star. (Photo: Dennis Morris)

Morris’s encounter with Marley was fortuitous. When he told his mother at home and the careers master at his school that he wanted to be a photographer, there was not much encouragement. “There is no such thing as a black photographer,” his careers master said, but the young Morris countered, “Yes, there is,” namechecking the African Americans Gordon Parks and James Van Der Zee.

When the careers master asked whether Morris wanted to shoot weddings, Morris was insistent: “No, I want to be a photographer.” The prevalent idea then, Morris explained, was that black photographers were good enough only to shoot the sentimental — weddings and babies — and not explore the other side of the profession: fashion and press photography.

Morris’s mother had “a very typical West Indian attitude: How are you going to make money from photography?” The impulse then was to follow the hackneyed path, becoming a doctor, a lawyer, mechanic or other “real” professions.

Morris had become fascinated with photography as an eight-year-old choirboy in the Church of England. Donald Patterson, a well-to-do benefactor and member of the church, had donated photographic equipment to the church for use by the boys.

It was he who was encouraging — “Dennis, you have the eye, the golden eye,” he said to Morris —and who from time to time lent the youth his Leica camera, and kept on saying to Morris’s folks, “He really has a future in photography.” Patterson’s words were not without basis: at only 11, one of Morris’s photographs had been printed on the front page of the Daily Mirror.

Sista Cool. In addition to his rock photography work, Morris also documented black Britons. (Photo: Dennis Morris)

Sista Cool. In addition to his rock photography work, Morris also documented black Britons. (Photo: Dennis Morris)

The work with Marley, which appeared on the front covers of the Melody Maker and Time Out and other magazines, must have convinced Morris’s mother that being a photographer was a viable profession, after all. But more than acceptance at home, it led to more opportunities in music, including a position as art director at Blackwell’s Islands Records, where Morris signed the poet Linton Kwesi Johnson (and designed the album cover of Bass Culture), and documenting the punk rock group The Sex Pistols. Morris’s work with the band was collected in the book Destroy: Sex Pistols.

For someone whose desire originally was to be a social documenter and war photographer, and whose hero was the British war photographer Tim Page, some might view Morris’s rock photography as a detour.

“When I started with the Sex Pistols, I found my war — because it was a very strange time; they spoke out against the establishment, against the queen. The same applies to Bob Marley,” he told me. Then referring to political violence taking place in Jamaica at the time and the attempt on Marley’s life, Morris said, “He was working at a difficult time, political violence; so I did find my war, but it was a musical war.”

Dennis Morris got his big break documenting The Wailers as they toured Britain. But he soon branched out into various subjects. (Photo: Pearl Morris)

Dennis Morris got his big break documenting The Wailers as they toured Britain. But he soon branched out into various subjects. (Photo: Pearl Morris)

Beyond the war, Morris also took on other projects, including documenting the Sikh community in Britain, working in China on the eve of the Beijing Olympics and, perhaps most notably, Growing up Black, a documentation of the West Indian community in the 1960s and 1970s.

“It’s a title I gave because when I was growing up, my generation was the first to be called black. My parents’ generation were called coloured people. We went from being called coloured people to being called black.”

Writing about Growing up Black in The Guardian, the British journalist Gary Younge noted, “But what we see in Dennis Morris’s pictures of black Britons in the 60s and 70s — collected together in a new book — both challenges the limitations inherent in that framing and provides a counter-narrative to it. For in the photographs of people at church and at play, styling and protesting during this critical period in our racial history, he transforms black Britons from objects to subjects and recipients of hospitality to cultural agents. We see not just a group of people shaped by their presence in Britain but shaping it: not content with being tolerated by ‘hosts’ they demanded engagement in their new home.”

The Brothers, Black House, Holloway Road, London, 1970 (Photo: Dennis Morris)

The Brothers, Black House, Holloway Road, London, 1970 (Photo: Dennis Morris)

The opportunities that Morris, part of the Windrush generation, later found wouldn’t have come easily had it not been for the encounter with Marley outside the Speakeasy club. In the film When Bob Marley Came to Britain, Morris recalls the reggae musician telling him, “Dennis, you have to remember that you are an exotic tropical plant that has been uprooted and replanted in a concrete soil. So you have to be strong to push through.”

Morris’s photograph of a sombre and, somewhat ashen Marley, guitar in hand, might be the last published picture on record. He didn’t know it at the time, but this was the last time Morris saw his hero. In 1980, there were rumours that the reggae man wasn’t well, but no one, except family and his inner circle, knew for certain what was wrong.

Marley was on a stopover in London on his way to Germany, where he was being treated, when Morris got a call. “I went to see him at the place where he was staying. This time it was different because normally when we met, he was such an energetic, bubbly person, so full of energy and so dynamic, but this time he was very, very quiet.

“We sat down and we spoke. I knew something was wrong but didn’t know what was wrong. Eventually he picked up the guitar and started playing a song. I didn’t realise it then, but I found out later that it was Redemption Song.”

Halfway into the deeply moving psalm, Marley asks, “How long shall they kill our prophets/ While we stand aside and look?” It didn’t take long to find out for, in another few months, on 11 May 1981, the prophet was dead, of skin cancer. He was only 36 years old.

• For more of Morris’s work, visit dennismorris.com

• When Bob Marley Came to Britain can be watched on YouTube