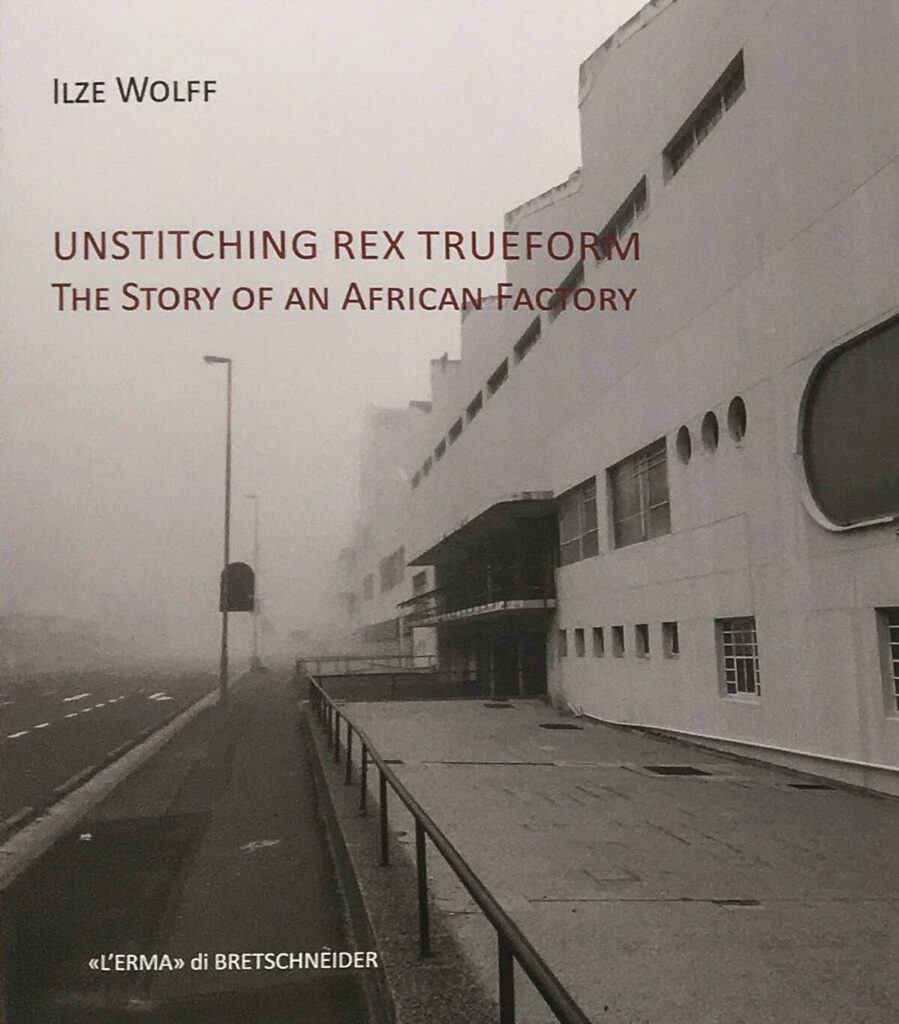

The Rex Trueform factory and building in Salt River, Cape Town. (Photo: David Harrison)

In a time of crisis and constraint — constrained movement and constrained budgets — can artists reimage unorthodox methods and unconventional modes of knowledge production? What possibilities can crisis offer to the development of new forms and new ways of seeing and experiencing artistic production?

Aiming to address the questions above and encouraging experimentation through the digital, the Institute for Creative Arts (ICA) at the University of Cape Town invited applications for its inaugural Online Fellowship Programme. The first of its kind, the online fellowship brought together 34 selected fellows with the idea of reconceptualising multidisciplinary projects as online renderings.

One of the projects, The Cutting Room Project, by artist and fashion practitioner Lesiba Mabitsela, engages these questions through critical inquiry into modernity and its role in defining culture and aesthetics. As a philosophical ideology, modernity regulated constructions of race, gender, sexuality and class around the question of “Who is man?” — resulting in a perpetuation of violent conditions of white supremacy through social, economic and political divisions. Those who were considered man (read human) were afforded full rights to own, traffic, possess, rape, kill and plunder; those who were not considered man could be owned, trafficked, possessed, raped, killed and robbed.

Understanding modernity as the underpinning of Western notions of beauty and aesthetics, Mabitsela offers an interesting study through which to reflect on history through fashion. This study responds to Ilze Wolff’s book, Unstitching Rex Trueform: The Story of an African Factory, in which she analyses the effects on class, race and gender through the modernist architecture of the Rex Trueform garment manufacturing factory in Salt River, Cape Town.

Beginning with a seductive video that places us at the intersections of fashion and architecture, the interactive storyboard suggests a consideration of the shared characteristics between “the three-piece suit” and modernist architecture. A medley of sound, text and image — interviews with old staff from Rex Trueform, differing designs of the suit and various angles of the manufacturing plant is set against a backdrop of scaled drawings of the city’s map, as well as a blueprint of a suit.

Mabitsela and I had a conversation that sought to contextualise the project’s inception, its form and its content — thinking through it as a potential gesture of site contestation, both in the digital and physical realms.

Lesiba Mabitsela’s The Cutting Room Project is a medley of sound, text and image that places us at the intersection of architecture and fashion.

Lesiba Mabitsela’s The Cutting Room Project is a medley of sound, text and image that places us at the intersection of architecture and fashion.

In the ICA Fellowship programme, your work is included under the theme “history and archive”. Can you explain how you think through these concepts?

I guess that it was because of a memory of a happy time that the project came to life. I was trying to capture a memory of my time as [designer] Gavin Rajah’s newest assistant. This involved processes of making patterns, cutting, stitching, beading, fittings and back again — an absolute commitment to make garments to the highest standards. There was often heated discussion about the work, especially in the early days.

Once these standards became second nature, flow between the different functions required in the atelier operated like clockwork. I started to observe moments of synchronicity, but also sonic experiences, such as the humming of a sewing machine, the songs that would play on Good Hope FM, the business of St George’s Mall outside, and the stillness that came with the Jumu’ah call to prayer on Fridays at midday.

Among these moments were conversations about the good old days when the garment trade was at its height in Cape Town, but also the bad, with homelessness (an ever-present sight in the city) and families living far from the city centre still waiting for houses promised to them in District Six. Within this picture is a wealth of knowledge on culture, spatial planning and politics that is rarely displayed in the world of fashion and certainly not in local fashion curriculums, obsessed with the allure of the Eurocentric ideas of fashion, which, now more than ever, are concerned with commerce rather than cultural effects.

The story of Rex Trueform became an opportunity for me to retell these stories (especially having been a fashion student in Gauteng) and by doing so acknowledge those who operate behind the scenes. At the time this project was conceptualised as a film documentary. In hindsight, there can (unintentionally) appear to be a narrative with the medium of film documentary. But durational constraints threaten the ability to adequately explain the different layers that need to be expressed about the garment trade sector in Cape Town and, by extension, South Africa.

The Cutting Room Project is a multidisciplinary response to Ilze Wolff’s book, Unstitching Rex Trueform: The Story of an African Factory

The Cutting Room Project is a multidisciplinary response to Ilze Wolff’s book, Unstitching Rex Trueform: The Story of an African Factory

I’m interested in the intersections between modernist architecture (its forms and structures) and how these relate to constructions of race, gender and class. Can you explain to us how Wolff’s book became an entry point for you? What does it offer?

The “modern” in your question is what I am most drawn to, because philosophical ideas around modernity shaped the structure of not only the building itself, but also the city of Cape Town. The idea that a modernist idea such as “form follows function”, coined by American architect Louis Sullivan, can be used not only to maximise commercial output and profit, but also to dictate cultural belonging (that is, race, class and gender) in terms of who is allowed in the city and for what function.

This is the same level of entitlement or access to spaces a tailored suit can afford a person, particularly men. Wolff’s research shows how segregation by class and race was built into the factory and, as the years went by, how Rex Trueform grew to become a contested space supported by the apartheid government. Wolff has a unique way of expressing this through her thesis, which predates the book; visually too, with an activist’s eye and an understanding of the sociopolitical factors surrounding the design of the building. Similarly, one must understand that the stiffness of the suit’s form as we know it found its roots in part from a celebration of colonial conquest, the influence of neoclassical beliefs about the body, the military uniform and ideas of gender sanctioned during Queen Victoria’s reign. This is a side story from the generally accepted dandified exploits of Beau Brummell — incorrectly said to be the first dandy and the father of the modern suit. Looking closer to home, one must observe where this power emanates — corporate culture, cultural or personal milestones, formal gatherings or as attire for “mabitleng”/burial grounds during funerals.

‘I found the connection between the suit’s construction, Rex Trueform and the City of Cape Town’s spatial planning through the idea of blueprints/ patterns/ maps,’ says Lesiba Mabitsela. (The Cutting Room Project)

‘I found the connection between the suit’s construction, Rex Trueform and the City of Cape Town’s spatial planning through the idea of blueprints/ patterns/ maps,’ says Lesiba Mabitsela. (The Cutting Room Project)

Can you tell us about the significance of the suit — then and now?

The irony is that nothing has changed; the suit is still as significant to male attire as it was a century ago. The garment has been reinvented many times by Japanese designers, by women in the eighties and by Africans before, during and after colonialism. It still carries that reputation for seriousness, trust and hierarchy. The only difference is that it is maybe worn to a lesser degree than it used to, but at least one tailored suit is sitting in the cupboard of most men.

Aesthetically, your project uses a series of dashed lines in very interesting ways. To me, these are reminiscent of the tracing of fabric before it is cut. Tracing, of course, can speak to marking history, trailing history and so on. Can you speak a little bit about your decision to use these dashed lines?

I am glad that you mention the process of marking before the fabric is cut, which I think I am open to accepting. I wanted to illustrate ideas of process, of planning and so I found the connection between the suit’s construction, Rex Trueform and the City of Cape Town’s spatial planning through the idea of blueprints/ patterns/ maps. We then decided to try to reflect the tailoring trade’s methodical use of tacking — a form of hand stitching used by tailors to shape certain parts of a bespoke suit — instead of a solid line. The wow factor would be the unstitching of the stitched lines that playfully paid homage to both the tailoring trade in Cape Town and Wolff’s book, aptly titled Unstitching Rex Trueform. Again this last part was a decision made through the process of making this work.

A street scene in Salt River, Cape Town. In his project, Lesiba Mabitsela wanted to acknowledge the people who operate behind the scenes and their wealth of knowledge on culture, spatial planning and politics. (The Cutting Room Project)

A street scene in Salt River, Cape Town. In his project, Lesiba Mabitsela wanted to acknowledge the people who operate behind the scenes and their wealth of knowledge on culture, spatial planning and politics. (The Cutting Room Project)

I love that the project contains oral histories through interviews. Can you tell us about how you think through the interaction of sound and text in this project?

As mentioned in my answer to your first question, these testimonies were as I had experienced in the atelier, to some extent. The difference is that there was no coronavirus to speak of, let alone the culture of Zooming. I think oral accounts capture emotion in a way academic writing cannot.

Oral communication can also be humbling, as I experienced, because I can be in my head a lot of the time trying to explain concepts to people. Using other voices helped to deliberately take the focus away from me being the artist achieving clarity in articulation of an experience and human connection.

One area you don’t highlight is the music used, which was commissioned to evoke a similar experience? I kept asking myself, “What music was playing while the workers at Rex Trueform were working?” The text was, as is usual with research, tracking or brainstorming processes, used to highlight, bookmark or map the important themes of the content and then playing with the arrangement of seemingly unassociated stories based on other forms of visual content, including the background layers or ideas. This was also explored with the Polaroids that had handwritten titles that were scanned in and placed on them, again simulating the aesthetics of process or making. Sort of remembering through labour.

A behind-the-scenes Polaroid from The Cutting Room Project

A behind-the-scenes Polaroid from The Cutting Room Project

A behind-the-scenes Polaroid from The Cutting Room Project

Can you tell us about why you decided on the format of the Polaroid to hold the structure of your project?

So I guess the star feature of the work became the Polaroids but looked at in its entirety I wanted to capture the original concept of a storyboard. Polaroids in themselves are nostalgic but also instant and unserious compared to a DSL camera. Polaroids are also used often in the fashion industry to take quick pictures during fittings and then drawn on to express alterations to garments. Although the images are permanent the placement is not, so I think there is an interesting idea related to permanence and non-permanence there. I guess it also has to be understood as the form of tech used after the sewing machine and before the large, high-definition cameras needed for fashion shows, photoshoots, fashion films, et cetera. It is the “behind the scenes”, just like the sample hands, beaders, cutters and finishers in the factory.

This article is published through a partnership between the Mail & Guardian and the Goethe-Institut that focuses on various aspects of innovation