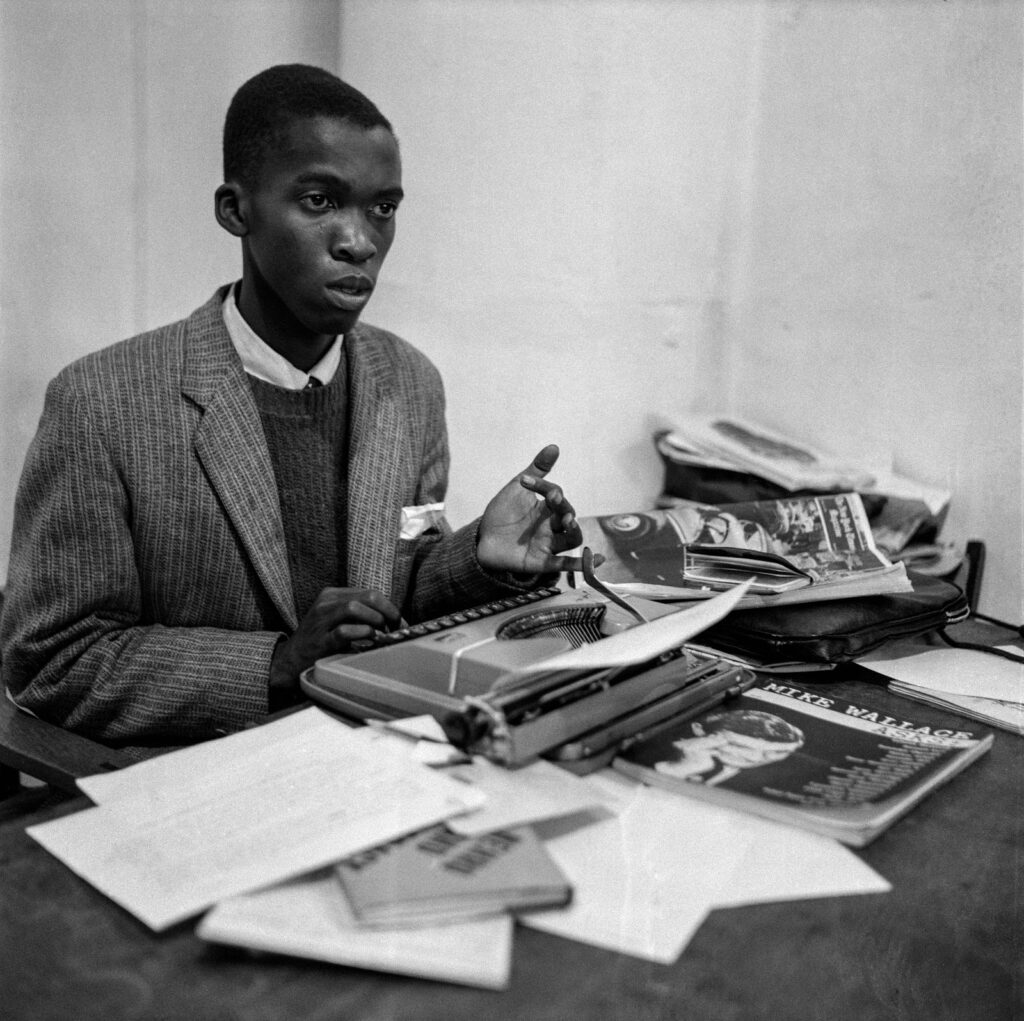

Songs of revolt: The world-renowned literary critic and broadcaster Lewis Nkosi was born in Durban in 1936. (Victor Dlamini)

Ten years after his death in Johannesburg, Lewis Nkosi’s work allows us to critique the country’s worsening fault lines, in the hope of animating all South Africans towards strengthening the fight against endemic historical injustices and poor service delivery.

Anchored on issues of colonialism, race, class, land, power, sexuality and the beastification of the black body, his 1986 debut novel Mating Birds is an enterprising sea map of the mind, the craft of writing, and his running commentary on how best black writers could produce a radical, imaginative and persistent response to the apartheid catastrophe.

The novel does not only critique the land as racist and oppressive, but it is also a critical reading of white texts (also as bodies), and their hegemonic positions in apartheid South Africa.

From the very first few chapters of Mating Birds, readers imagine themselves entering a “blood-stained gate”. Rape is one of the most brutal violations of someone’s body, and in the book, Ndi Sibiya, the main character, is accused of having raped a white woman, Veronica Slater.

Mating Birds is also a world of violent reveries and the rediscovery of revolutionary agency. In this palimpsest, Nkosi kindles harbingers of a similar sentiment in two South African fictional autobiographies, Es’kia Mphahlele’s The Wanderers (1971) and Chabani Manganyi’s Mashangu’s Reverie (1977). Referring to these two texts, literary scholar Prof Kgomotso Michael Masemola argues: “Reverie of the violent kind, highlighting a revolutionary impulse, particularly disavows victimhood as it insists on action, intersubjectivity and freedom.”

Es’kia Mphahlele’s The Wanderers (1971)

Es’kia Mphahlele’s The Wanderers (1971)

The deployment of psychoanalysis in the works of Lewis Nkosi, particularly in Mating Birds and his second novel, Underground People (2004), is a conscious political act that draws inspiration from, among others, the scholarship of the eminent black psychiatrist and African liberation activist Frantz Fanon.

It centres Nkosi’s ideas on what critic Therese Steffen calls “the body in excess” and his ability to let the psychoanalytical eye make pronouncements on race, oppression, sexual desire and the politics of the body, thereby exposing key aspects of South African black-white relations under apartheid. It also exposes the excesses of desire and political power within the ranks of the oppressed, as shown in Underground People.

In Mating Birds, music is resistance. Black power. The songs are a coping device for the prisoners — their ways of staying alive and sane. Songs are a subversive gesture of political solidarity among the prisoners.

For Nkosi, even if Sibiya’s heinous crime may generally be seen as non-political, the revolutionary songs that the prisoners sing are also for him. The reader therefore sees Sibiya, not just as the listener, but also as the writer of the songs — the spokesperson of the sentiments the prisoners are expressing in their forbidden songs. By translating and committing his thoughts and feelings to writing, Ndi Sibiya accentuates the idea of the novel as history and the prisoner-writer as the primary witness to injustice.

In the novel, alienation is not just a personal condition, but also one brutally predetermined by history and the sociopolitical injustices of the times. For Sibiya, inside the white man’s court, even the elements are oppressive — the heat is “unbearable”. The writer draws attention to the political temperature and its systemic predilection for finding a black person guilty without the benefit of a fair trial.

Lewis Nkosi’s Mating Birds (1986)

Lewis Nkosi’s Mating Birds (1986)

In the novel, Sibiya thoroughly mocks this absurdity, portraying its ritualistic emblems with self-deprecating humour, evoking a voracious James Baldwinian, ironic register.

“I am the eternal goat being prepared for sacrificial slaughter,” says Sibiya, “and, of course, I’m bored with the prolonged but clearly necessary preparations for the ceremonial shedding of blood.”

For Nkosi, apart from focusing the mind intently until all is spilled out, writing is a metaphor for the (re)excavation of memory. The ambivalence speaks to the possibility that someone writing under conditions of imprisonment and injustice is not really “free” to fully get their life back, but perhaps can take charge in the narration of their memory. Therefore, for the political prisoner, “the story of my life”, in Nkosi’s imagination, seeks to confront the master-narratives of the black-white encounter as loaded speech and the dance of the body and its sexual urges.

Nkosi, who was born in Durban in 1936, throughout his work sought to affirm blackness as consciousness; a song of revolt that sharply spoke to the historical and class revolt imperative and the return of white settler-occupied land to black people. Alongside notable modern black thinkers such as Fanon, Es’kia Mphahlele, Miriam Tlali and Ngugi wa Thiong’o, his major intellectual and political concern was, unashamedly, the black condition, and the quest for black liberation everywhere. Notably, as a world-renowned literary critic and broadcaster, he was dedicated to examining leading literary texts from the black world.

After leaving South Africa in 1960 on a Nieman fellowship to study journalism at Harvard University, Nkosi became one of the most respected African literary critics in the world. At the time that he emerged as a critic of consequence, he was in stellar company, with Abiola Irele, Ezekiel (now Es’kia) Mphahlele, Wole Soyinka, Gerald Moore and Ulli Beier, to mention a few. These critics were relishing the rise of the African novel and poetry (mainly in English and French) at the time of African independence (and its discontents). It was a fruitful season of African affirmation, agitation and Pan-Africanist solidarity, stretching from South Africa at the tip to the rest of Africa and the African diaspora. The invigorating slogans — Mayibuye, Pamberi ne Chimurenga, Freedom! Hedsole! Sawaba! Uhuru! and Black Power — were all key emblematic words in the broad grammar and unfolding drama of black revolt and liberation.

Much of Lewis Nkosi’s writing dealt with what the author calls the ‘musicality of place’, the yearning of an exile. (African Image Pipeline)

Much of Lewis Nkosi’s writing dealt with what the author calls the ‘musicality of place’, the yearning of an exile. (African Image Pipeline)

On the other hand, in South Africa, the period was marked by worsening apartheid repression. Milestones included the banning of the ANC and the newly formed Pan-Africanist Congress, the Sharpeville massacre, the birth of Umkhonto weSizwe, the birthing (in essence) of the “underground movement” and the historic Rivonia treason trial.

Nkosi suggested that South Africa resembles a monstrous mental asylum, comprising various psychiatric wards from which vicious bodily and mental attacks are unleashed on black people. He historicises these brutalities, often dissecting them as tragicomic but well-engineered political systems of profit-making, oppression, class exploitation, racialised violence and exclusion. His work contributes to the task of self-identity and freedom, advancing possibilities for black people to retrieve affronted collective and individual histories, to recalibrate and retrace violated mental and spiritual maps.

For him, South Africa’s condition is not neurological; neither is it a mental ailment where madness is a “natural” loss of one’s cognitive faculties. Instead, he exposed the political absurdity of the whites-only state and the Bantustanism that characterised its land dispossession and Christianising missionary zeal. In Wa Thiong’o’s words, Nkosi understood that colonialism comprised, not only “the sword and the bullet”, but also, the “psychological violence of the classroom”.

In his fretful dance from exile, Nkosi was disappointed that fiction by black South African writers lacked the vitality of African music. What he missed in the writing was the ability to exceptionally adapt “to the challenges of the disintegrative tendencies of city life with an amazing suppleness and subtlety”.

His search for what I call the musicality of place is, undoubtedly, a major life force inscribed in his work. The search for this musicality was perhaps more severe for someone largely displaced by force from his country, and only connected to home through memories, friends, books and the mass news media.

Lewis Nkosi’s Underground People (2002)

Lewis Nkosi’s Underground People (2002)

For the exile, home is “experienced” by remembering family rituals, songs and tales from the once-familiar place called home.

Nkosi loved urban black music varieties, often epitomised by big and expressive mbaqanga township bands led by distinguished musicians. The latter were mostly self-taught, but some had acquired a certain amount of formal music education through apprenticeships in church choirs and bands, private tuition or distance learning. Both he and his childhood friend and fellow writer, Nat Nakasa, played the piano.

Exile also allowed him to travel, see the world, and embrace its diverse pleasures. Increasingly, Nkosi’s language of place and time became that of an insider/outsider. In his essay, Doing Paris With Breyten, he is comfortable in modern Paris — his love of this city is palpable. In 1965 he wrote that his first “visit” to Paris came through books in his boyhood, through “the literary embodiment of European history” by the works of Dumas, Flaubert, Balzac and Hugo. Despite its well-marketed allure, the real Paris, as he experienced it, was a place with a delightful yet ambivalent countenance, one he captures with telling invocation in the essay.

While hosted by the exiled Afrikaner poet and painter Breyten Breytenbach, and after being moved by the exiled Mazisi Kunene’s Zulu dance, Nkosi writes the exiled African-American painter Beauford Delaney “looked both sombre and fervid, sad and ecstatic, already started on that long journey into the dark night of the Negro psyche where every question leads to the nightmare of the slave ships”.

The essay uses the first-person voice, the autobiographical account functioning to make the narrative immediate and hard-hitting. In as much as the swing of emotions is reserved for Delaney, it could well be that this veiled brooding referred also to Nkosi and his two fellow exiled countrymen. After all, as time slowly slipped past, South Africa loomed ever larger in his memory and literary imagination. Home was not simply “where the music is at”, but also a distant place that many exiles could hardly recall without a sensible staccato of tears. This comment is not made glibly but is based on a traceable inclination towards the autobiographical turn in several writings.

Throughout history in many countries, writers and writing provide a powerful way for modern society to talk with itself and express the possibilities of its reimagination. Writers greatly contribute to narrating history, identity issues, and notions of right and wrong in society. As shown by the likes of Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison in the United States, many writers have been critical in pricking a nation’s conscience and broadening progressive ideas in society. Without necessarily taking up arms or addressing mass rallies, in their unique way, we need writers and artists in general, to contribute towards positive social change and disavow ideas that kill lives and dreams.

Literary historian Andries Oliphant suggests that Lewis Nkosi uses language for something much bigger than everyday speech, mostly irony. Oliphant argues that Nkosi wants to accord to literature the last word on the South African question. “Nkosi’s ironic register is trained on the crisis of the period just before the transition from minority rule to democracy. In its ironic play with appearance and reality and the imaginative energy which drives the narrative, it dramatises the release of the literary signifier from the choking grip of history and social reality to suggest a space where meaning is neither given nor transparent, but constructed perilously.”

This is a shortened version of a chapter published in Mintirho ya Vulavula: Arts, National Identities and Democracy in South Africa, a Mapungubwe Institute for Strategic Reflection (Mistra) publication edited by Innocentia Mhlambi and Sandile Ngidi. The book examines the role of arts and culture in social cohesion, socioeconomic transformation and nation-building. Mistra takes a long-term view on the strategic challenges facing South Africa