A still from the Lerato Shadi-directed video, Re Maotwana Gonyela (2018), featuring dancer and choreographer Sello Pesa.

The “black struggle” has been idealised and romanticised in popular culture in ways that I suspect people don’t really embrace. I don’t see a movement feeding the people, and educating and organising like in the old days … Who is doing that now? Or is it: “How can I make money by looking black and acting black and wearing these buttons and T-shirts,” as opposed to “How can I build an institution?” There are people who are really working, but their work is often hidden as the commodified activism is celebrated. — Marilyn Nance, in an interview with Fanny Robles in Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art (Global Black Consciousness, Number 42-43, November 2018).

It is revealing that Lerato Shadi, in a 2016 National Arts Festival talk with scholar Neelika Jayawardane, refers to the presence of Berni Searle and Tracey Rose in the art world (she encountered their works at the Johannesburg Art Gallery, where she had her first show in 2007) as having had a great effect on her.

The statement is partly a straightforward acknowledgment, but it is also pegged to the complicated ways in which Shadi continues to experience the gallery as a space of performance, exhibition and commerce.

On the one hand, Shadi seems to celebrate the force of her artistic ancestors (“Seeing a Berni Searle retrospective there really did something for me”); on the other hand, in her work and in that particular interview, she seems to question the terms under which women like her are included in the art world.

Searle and Rose, primarily through the use of their bodies, have sought to resist easy compartmentalisation and commodification, with Rose stating in a 2019 interview with Zaza Hlalethwa in the Mail & Guardian that she “…was more interested in how to transcend the body”.

The centring of women — their labour, their intellect, their refusal — is something Shadi continues to “play around with”, especially given how much her practice remains aware of ancestry in action and how “our physicality dictates how we move through the world”, as she says in an interview with curator Dr Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung.

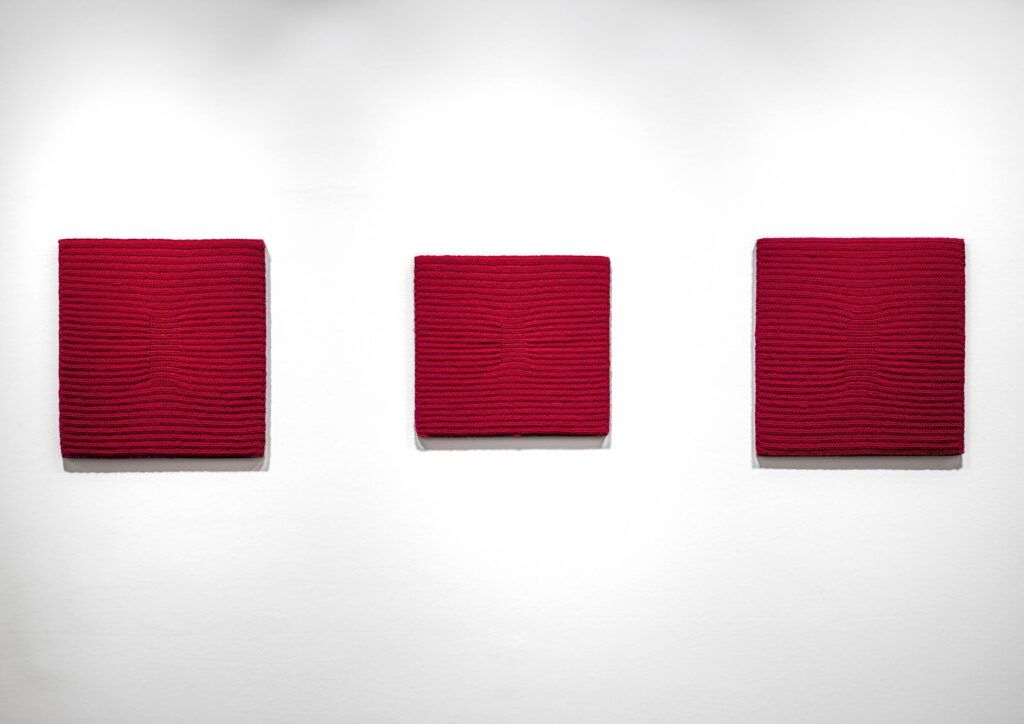

In the works that make up her last exhibition, Maru A Pula is a Song of Happiness, which recently showed at the Kindl Centre for Contemporary Art in Berlin, Shadi continues to reflect on her own process and its exploration of unacknowledged work, combining signature works like the seven-hour-long knitting video Selogilwe with newer relics like Series #1-4 which consists of crocheted works attached to canvas.

I Know What a Closed Fist Means (2020), consists of four photographic prints of oversized fists in which the artist challenges universal assumptions.

I Know What a Closed Fist Means (2020), consists of four photographic prints of oversized fists in which the artist challenges universal assumptions.

Spurred on by open-endedness of her work, Shadi’s palette continues to widen, with recent works like I Know What a Closed Fist Means and Re Maotwana Gonyela possibly giving a nudge to a reappraisal of the accoutrements of struggle and the toll of top-down ideas of nationhood. In this interview she speaks about the evolution of her work.

In your most recent exhibition, Maru A Pula is a Song of Happiness, durational work is still the foundation, although the end results are presented in various forms. How did you land on that method of working; where the work regenerates itself?

My entire practice is a durational practice. The first performance I did was a durational performance that took about three hours. I was still studying. In the first show I had, which was with Khwezi Gule at the Johannesburg Art Gallery — he had this project space there — I showed Hema.

Hema was a six-hour performance I did in an office space in Cape Town where I breathed out only into balloons. The end product was a five-minute video of that performance. The idea of durational works, the ideas of labour, the values of labour are also always in my work.

The red carpet [a crocheted scroll of wool from the work Mosako Wa Nako] at Goethe on Main in 2016 was from a 10-day performance: from 10am to 4pm I just sat and knitted. That carpet had just come from the National Arts Festival. It was the idea of looking at the importance of labour and how we value it. I kinda like thinking of it as a monument to unsung labour that makes spaces of privilege like galleries possible.

The durational works are mostly older works. At the recent show at Kindl, there was a seven-hour video showing [Selogilwe]. The Kindl video doesn’t have an audience and I like thinking of it as an hourglass. If you think about it, the people who get the most out of the work are probably the people that work at the museum, like the guards, who see it every single day.

A video still from Selogilwe video projection (2010).

A video still from Selogilwe video projection (2010).

Two people who come to see the show never see the same moment at the same time. The works are a meditation on how we consume video art because I’ve also made 10-minute, five-minute videos. Normally, in museum or gallery spaces you come in, you sit, you look at it and you wait for the moment you last saw to complete the loop and then you stand and you go. With a seven-hour video you can’t do that …

The other knitted works [Series #1-4] also relate to durational work. In doing those works, I adhere to a strict schedule of working: meditation, journaling and then crocheting until around 3pm — and then I work again from 8pm to 10pm. And that was like that until I finished with the piece. The bigger pieces took two weeks or three weeks.

The first week I adhere to a strict diet. I’d just drink [liquids] for seven days. Then I realised I needed a little bit more energy. For the second piece, I did a fruit diet, where I only ate fruit for the first week and the other three weeks I continued with the fast, because I wanted the body to be active considering what I’d be doing.

Besides the performance aspects, there seems to be a thematic continuum, with aspects of the land question coming more to the fore. The crocheted pieces remind me of maps or topographical shapes, or even landscape paintings.

Well, they are kind of landscapes of my time while I’m knitting them, but what I enjoying about what you are saying is that the works are so minimal and so repetitive. I always enjoy how they are open to evoking different images from different people. You can sit in front of them and allow your imagination to bring up associations.

A triptych of crocheted relics attached to canvasses from Series # 1-4 (2020).

A triptych of crocheted relics attached to canvasses from Series # 1-4 (2020).

How did you come to understand their subtle textural power and what does it bring up for you?

Through the years of work, it’s been a process where those two-dimensional works are not very two-dimensional. They have this sculptural texture to them. Those works came about through years of working. Selogilwe [the seven-hour video] is the oldest work on the show, which was like 10 years ago.

The other works we are talking about I did them last year: 2020. And then Ngono le Nna, the X and the signature, I did them in 2019 and the fists [adapted from a video work titled Mabogo Dinku] in 2020. Selogilwe is there to connect and give the idea that the crocheted works are connected to years of working within that genre of performance — and breathing and labour and knitting. But I hope it is evolving and will continue to evolve.

In your interview with Ndikung at Kindl, you speak about the title Maru A Pula. It struck me that it is apt in so many ways. The subject of the song may be dark, in the sense that it speaks of a drought, but it also represents the joy of repetition, or ritual, in this case pleading for rain.

A lot of my titles are in Setswana and I think that one of the main reasons is that I feel that I shouldn’t have to excuse who I am and I don’t need to translate myself. Ke Motswana. Toni Morrison has spoken to this, in response to a question in an interview. She was asked: Would there ever be a time when a Toni Morrison book is about white people? She went [something like]: “You don’t know how profoundly racist that is? Would you ever ask a white person if they’ll ever be a time when their books are about black people?” In another [interview], someone said, “You write about the black experience?” She said, “Why is it the black experience when you don’t say Tolstoy writes about the white experience?”

Thinking around that and how it’s okay to create from where you are and that should be celebrated — I think that’s where that comes from. A lot of the time I play around with it a little bit. For example, in Ngono le Nna … I am very much aware that it’s mainly Tswana speakers who will understand that [title]. But I also know that marginalised people don’t have a problem with not fully understanding. It is mainly people who are used to being spoken to [in their own languages] who usually demand a translation. Maru A Pula is a Song of Happiness comes from that idea.

A partial installation view of Ngono le Nna, a neon light work in two parts (2020).

A partial installation view of Ngono le Nna, a neon light work in two parts (2020).

Also, what I’ve noticed is that a lot of the time in Europe it’s, “Oh, rain is coming,” and it’s seen as something that’s not good. Whereas at home it’s like, “Pula a ene!” — the idea of rain quenching a thirsty earth. With Bonaventure, we were talking about how when it rains in Southern Africa — also in Cameroon — the earth has a different reaction. In Berlin, you don’t have the same smells.

Continuing with allusions to land, the video Re Maotwana Gonyela is brilliantly evocative of a yearning, which makes me wonder where was it made and why?

It was made in Makouspan in Rooidam. My grandparents own a small piece of land there and I knew it was important that it was made in that space, also considering the ideas of land ownership in Southern Africa.

I see the figure as a personification of resistance and the idea that black people have been resisting different types of oppression for a very long time. I was also thinking about how the almond hedge in Cape Town [also known as Van Riebeeck’s Hedge, planted in 1660 to seal off the Dutch East India Company’s new settlement] is symbolic of the first apartheid wall and how that was also resisted. A lot of artists recently have also been speaking about the first ship that landed in the Cape before Jan van Riebeeck and how the indigenous people fought back.

I was thinking about the idea that whenever there is oppression there is resistance, and meditating on that spirit. I knew that Sello Pesa was interested in mining everyday movement in his choreography as well.

It was important that when the viewer is looking at the video, they never think, “Wow, that’s a great dancer.” I didn’t want his fabulousness to distract the viewer. But when you are looking at the video, you think about how the movements of the figure are sometimes concentrated and sometimes very random.

He captures the spirit of a lot of my work by allowing the viewer to have this moment of really looking at the work, looking at the moments, looking at the landscape.

At what point did meditation as preparation become a part of the work and a part of your life?

With my first work, Hema, that’s when I started dabbling in meditation, so as to be able to breathe out only into balloons for six hours. I needed to go to a meditation class and I needed to consult with a guru. He did say he was a guru. He had studied with so and so and so and so. I went to a yoga class that incorporated meditation and I spent some time talking to a yoga teacher about breath and I told them what I wanted to do.

A video still from Hema (2007).

A video still from Hema (2007).

A video still from Hema (2007).

He kinda walked me through what I needed to do, how I needed to do it and how to “cheat” so I could survive the six hours. So one way to cheat was to breathe in, pause, and then breathe out, and then pause. The pause was important. I don’t remember exactly how, but I know it was important in helping me catch my breath or steady myself.

So preparing for that six-hour performance, and then again, the seven-hour video, I needed to go into meditation a little bit more so that I could sustain being able to do that for that long.

Does it take a heavy toll on the body?

Most unappreciated labour takes a toll on the body. The most famous [example] at the moment is Amazon workers. I have a cousin who worked at a chicken plant and she was telling me about the kind of hours that they did, where they stood without a break, and that while she was working she saw somebody’s finger getting cut off.

I’m comparing my practice with unsung labour: the labour that people do, not for seven hours or 10 days, but for years and years. It’s not really a big comparison.

Works from Maru a Pula is a Song of Happiness can be viewed on the Kindl website and at and on the artist’s own website.