Alternatives: Mosie Mamaregane acts in the Kwasha Theatre Company’s performance of The Empire Builders, described as an audio experience. (Photo: Oscar Gutierrez)

Theatre endured an unprecedented year of suffering caused by Covid-induced mass closures and job losses. Nationally there has been a push to develop content for digital platforms through live streams, filmed performances, audio drama and more. Comedy and music have fared better, but there has been an uneasy transition for traditional theatre.

One of the biggest challenges for this transition in South Africa are data and technological infrastructure limitations. Added to that are the financial costs of producing for online and unclear business models.

As the coronavirus lockdown commenced, many theatres streamed pre-recorded material of past work, but were optimistic about the possibilities that digital platforms presented.

Much of the work created in the past year was lo-fi and made using minimal technology or shot with only one or two cameras. The National Arts Festival took the brave leap to transpose the entire festival online, encouraging participants to rethink presentation of their work. State-funded theatres redirected annual artistic budgets to support the creation of work for digital platforms. For example, the Performing Arts Centre of the Free State in Bloemfontein spent nearly R1-million of its artistic budget on commissioned pieces to be streamed on Facebook.

In a sink or swim move, artists and theatre practitioners have needed to urgently upskill to reinvent and innovate new ways of showing their works. Although there was an initial excitement for this kind of work, it seems theatre audiences have been slow to adapt to online consumption.

Looking ahead

Tin Bucket Drum, a play by Neil Coppen, is an absorbing one-woman production celebrating African storytelling. It’s perhaps more compelling because it was filmed in front of an audience. It is part of the works featured on South African Theatre on Demand, an online platform launched in June by arts administrator and producer Blythe Stuart Linger. It is a monetised online video-on-demand service, where audiences can buy content for individual productions. The platform is not funded, nor do artists pay to have their work made available.

Tin Bucket Drum by Neil Coppen is one of the works shown on the online platform South African Theatre on Demand, which was launched in June. (Val Adamson)

Tin Bucket Drum by Neil Coppen is one of the works shown on the online platform South African Theatre on Demand, which was launched in June. (Val Adamson)

Commenting on how work has moved to online, Linger says, “It is challenging to retain the attention of an audience member. It’s also difficult to translate a play onto a screen, which is essentially a flat surface. It has to be changed to be more filmic. But there are innovative ways to translate these feelings from stage to screen.” These include film and editing techniques, camera angles and looking for new points of engagement.

Linger says the platform sales have slowed over lockdown. “It’s difficult to get bums on seats in the real theatre space, and it’s the same for selling tickets online.” Despite the number of views reached, Linger says evaluating how audiences feel about watching theatre online is difficult.

Expanding theatre

Actress Jemma Kahn recently launched Jemma in the House! bringing theatre to the homes of audiences. As a result of a difficult financial situation and uncertainty in theatre, Kahn narrowed down three performances she could present, including hit play The Epicene Butcher. These will be done in front of small audiences with minimal tech.

“I don’t think theatres or festivals will be back up and running in any meaningful way this year. This is not a criticism but a reality. And having performed Jemma in the House! now, I witnessed how delighted people were not to be watching Netflix … One lady even cried tonight, she said, ‘I haven’t seen anything live in so long. I am so moved’.” Kahn adds, “I’m relieved that the idea has traction because until I’d performed I wasn’t sure it would. It also cannot be overstated the feeling of relief I have to once again be in control of my finances and career in some small way. Psychologically it’s huge.”

Jemma Kahn at the National Arts Festival in 2016. She now takes her theatre to people’s homes. (Photo: Dani O’Neill/Cue)

Jemma Kahn at the National Arts Festival in 2016. She now takes her theatre to people’s homes. (Photo: Dani O’Neill/Cue)

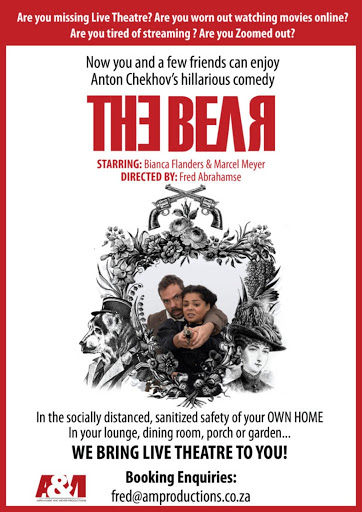

Similarly, in December, award-winning company Abrahamse and Meyer Productions advertised an “order-in” performance of Anton Chekhov’s The Bear with the poster asking, “Are you tired of streaming? Are you Zoomed out?”.

On the flip side, online allows space for innovation beyond the stage. It fuses interactive media and storytelling. Another Kind of Dying by Amy Louise Wilson was adapted as a 360-degree virtual reality experience. In October, dance collective Darkroom Contemporary created Deus::ex::Machina in the form of live dance performances that could also be played as an old-school arcade game online. Public arts festival My Body My Space runs until the end of March, hosted entirely on WhatsApp. It’s a “festival on your phone” with more than 80 new works.

Months ahead of the game, in June last year Faye Kabali-Kagwa produced The Shopping Dead — an experimental theatre performance done on WhatsApp. Kabali-Kagwa says she was interested in exploring a low-tech form that audiences could enjoy and actors could create. “I’ve been fascinated with WhatsApp for a while now, especially with the ubiquity of it on the continent. I thought rather than try get people to come to your website, why can’t we try to bring theatre to a platform that is already heavily utilised.”

The piece is a fast-paced dramedy that follows a day in the life of four retail employees, which unfolds through text messages, voice notes, gifs, memes and video. It was viewed by more than 600 people, with a large number from the rest of Africa.

This year, the Klein Karoo Nasionale Kunstefees (KKNK) ran a rigorous programme of online events consistently throughout the year to continue supporting artists. This included creating a virtual art gallery, commissioning home-based short films, an online live music series called the KKNK Mothership Sessions and launching an e-commerce site.

Artistic director Hugo Theart says, “I found it really interesting because it’s a new world for us. Everyone who jumped into this had to experiment and also provide quality and look professional.”

Theart sees lots of positives of online platforms, saying it’s about creating an experience with the medium that you’re using. “This has forced the arts industry to think differently about our industry, it has also led to wonderful collaborations.”

In December, award-winning company Abrahamse and Meyer Productions advertised an “order-in” performance of Anton Chekhov’s The Bear.

In December, award-winning company Abrahamse and Meyer Productions advertised an “order-in” performance of Anton Chekhov’s The Bear.

After losing its physical space, POPArt Theatre in Johannesburg kick-started the process of producing work online. Three weeks into lockdown they were already hosting an online student festival. Since then, they have been consistently working on performances, play readings, poetry sessions, open mic nights, JBOBS Live and Zoomprov experimentations. Co-director Hayleigh Evans says, “We have really tried to stay away from trying to record theatre, so our work is super experimental and mostly created with the idea of keeping the live experience and the spirit of gathering alive in one way or another.”

It is interesting that protests for action against the government has been championed predominantly by the theatre industry. A tweet by Arts and Culture Minister Nathi Mthethwa in January, stating “South African theatre is alive and well”, received immediate backlash born of frustration. The result was a petition calling for the removal of the minister.

In September, a group practitioners in the sector created the Sustaining Theatre and Dance (Stand) Foundation as a way to support theatre and dance even beyond the pandemic. Playwright Mike van Graan, who is part of the foundation, says of online work, “What we learnt last year is that we just don’t have the skills within the theatre sector to take theatre on to online platforms that translate effectively into theatre productions. So, when you are competing against something like Netflix, we simply don’t have the production values to sustain an audience.”

He adds, “I think that people were desperate to find an outlet to reach audiences, to generate income, so they went the online route without necessarily having the technology or skill to do it, so the production value often has been very poor.”

But Van Graan believes that training institutions will start equipping theatre-makers with the technical skills required to be competitive on online platforms.