An illustration that features a figure of Mansa Musa holding a gold coin. (Photo Credit: Historical image from the 1375 Catalan Atlas)

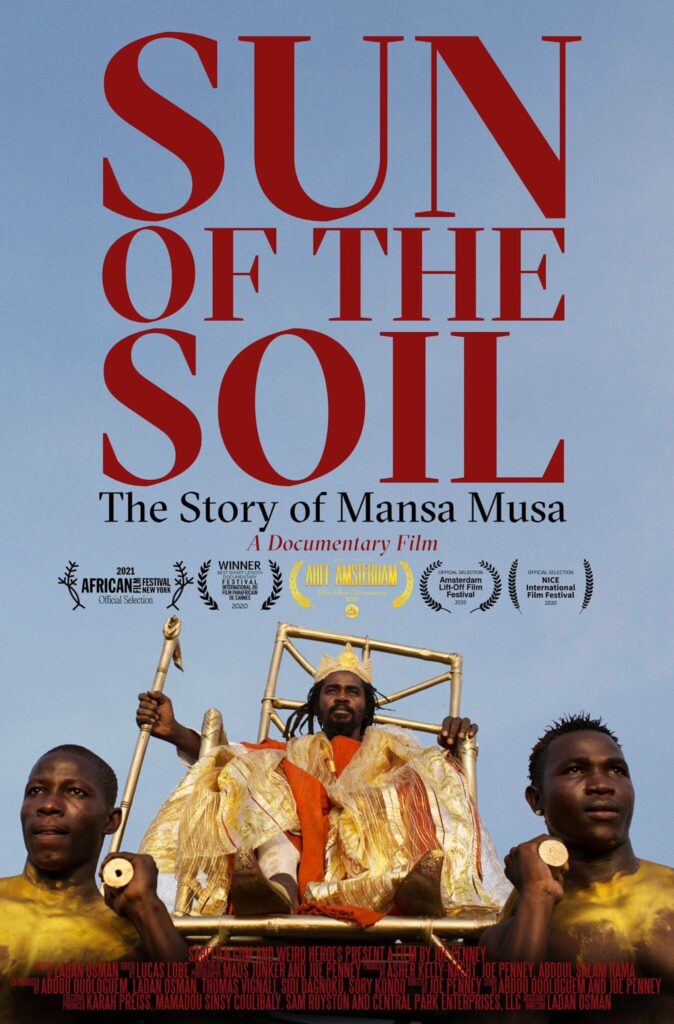

The void of written records about Mansa Musa, king of the Mali Empire (1312-1332) is deeply troubling. This is the subject of director Joe Penney’s 26-minute short performative documentary, Sun of the Soil, which featured as part of the 2021 New York African Film Festival. Written by Ladan Osman and narrated on camera by contemporary Malian artist, Abdou Ouologuem, the film is the fruit of the trio’s ongoing creative collaboration, striking a three-way balance between poetic lyricism, organic art, and pristine cinematography.

Sustained throughout by a motif of unearthing — digging up, excavating — the narrative follows a three-act structure that seeks to make sense of and, ultimately, undo the erasure of this figure seven centuries hence. Ouologuem asserts that Mansa Musa was a great king — under whose rule written manuscripts flourished and who built mosques, including the Great Mosque of Djenné. So why is there such a lack of information about this figure, whose grandfather’s brother, Soundiata Keita, is so well documented?

Leading scholars in Islamic studies, history, literature, and gold recount a well-organised critical viewpoint, leading Ouologuem to admit that the king posed a grave danger to the Mali Empire because he exhibited its wealth to the world, notably while on his lavish two-year pilgrimage to Mecca. But Ouologuem is not satisfied with this.

The opening act presents an impromptu modern-day gold rush, captioned with: “In 2016, villagers in Niono, southwestern Mali, found priceless gold jewellery, swords, and pottery buried in the ground. […] Some suspect the gold belonged to the legendary king, Mansa Musa, the richest person in the history of the world.”

A haunting acoustic improvisation accompanies a series of wide-shot pans across holes and mounds of red earth as local residents nonchalantly try their chances at striking gold. The title of the film appears in deep red accompanied by eerie music and a smooth cut to an aerial drone camera flying backwards opposite the oncoming crowd of cars and motorbikes in present-day Bamako. Next the camera fixes and tracks main protagonist and narrator, Ouologuem, riding his motorcycle through the city. The movement is stilled when viewers arrive at his minimalist studio. His natural materials are propped strategically on display, as is a tortoise — a symbol associated with high spirituality, particularly in the Dogon region — clearly in reverence to his late father, whose story also needs unearthing.

Sun of the Soil addresses the void of written records about Mansa Musa, king of the Mali Empire (1312-1332)

Sun of the Soil addresses the void of written records about Mansa Musa, king of the Mali Empire (1312-1332)

The scene is set with a final long take of the artist staring directly into the camera as he shares his commitment to be one with the elements, how his art materials reflect that, and how it all reflects the responsibility he feels to preserve Mali’s history, its natural environmental resources, and its communities.

Before the 15th century when “most of the world lived off the economic world created by Mali through the circulation of gold … [it] was mainly Malian gold that, prior to Mansa Musa, fueled the minting of gold currency in Andalusia and fed European and Asian trade.”

In act two, the documentary narrative is a tight weave of expert interviews, recent Sahelian news footage, and scenes contrasting past and present blended with kora and guitar music. The West’s construction of historical narrative is proven (once again) bogus, particularly for its active erasure of an African past, including European colonisers’ theft of manuscripts and its insistence on referencing transatlantic slavery as the beginning of African history. This part of the film argues for the recovery and revision of history, which, in spite of being copiously documented in “hundreds of thousands of manuscripts,” was relentlessly pillaged, erased, and rewritten.

In a final act, Ouologuem sees the only viable solution to be through art and performance. Spoiler alert: act three of the film is a theatrical re-staging of history curated brilliantly by the creative artist-director-writer trio. Ouologuem wants to “relive” the past and “recreat[e] history through art”. He wants to retell the stolen historical legacy of the land of his ancestors and of his father. The artist who felt compelled to return home after more than a decade abroad designing sets and costumes for the theatre is also a homonymous “son” of the soil; the artist’s work with the “sun”, or gold, and other natural elements of his homeland reads as a homage to this land.

Documenting the region’s present through the excavation of the past, with responsible critical awareness, Sun of the Soil is a form of artivism that aims to engage not only local communities through street performance, but also global communities through gallery photographic exhibitions of the sculptures, jewellery, props, and costumes of Mansa Musa.

This is an edited version of an article first published by Africa is a Country.