Raoul Peck’s new series is propelled by a white male archetype portrayed by Josh Hartnett. (HBO)

Haitian director Raoul Peck’s four-part HBO film series Exterminate All the Brutes starts with a powerful premise. The series promises to situate the history of white supremacy squarely within the concepts of civilisation, colonisation, and extermination that provided the ideological and material backbone for the construction of whiteness. Drawing from a statement made by his friend, the author

Sven Lindqvist, Peck assures the viewers that we already know this history, insisting that “it is not knowledge we lack … what is missing is the courage to understand what we know”.

Unfortunately, rather than giving the audience the courage to understand the history of colonialism, Peck instead centres white men as the makers of history in a way that re-inscribes notions of white superiority. The decontextualised photographs, illustrations, and reenactments that fill the series further reduce the victims of colonisation to passive spectators in history. In his attempts to name and portray the violence of colonialism, Peck perpetuates that violence himself.

Peck presents the series in the style of a personal essay, detailing his understanding of the history he narrates. Yet for a series that is intended to challenge white supremacy, Peck curiously centres a white male archetype, played by Josh Hartnett, as the protagonist. Episode one showcases a dramatisation of an 1836 battle in which a Native American woman from the Seminole nation challenged the US government’s efforts to take her land and enslave her black friends. In the ensuing scenes, Peck’s white male archetype, who appears in the first episode as a military general, shoots the woman point-blank in the head. A few frames later, the general grabs her lifeless body from among the fire-charred black and Seminole bodies scattered on the battlefield and scalps her, holding her severed flesh and hair to the camera.

It is not clear what function these gruesome scenes serve beyond their shock factor. In this representation of US colonialism, Peck casts the woman and her comrades as no match for the awesome power of the white man, who emerges from the battle triumphant and unscathed.

Peck on set with Josh Hartnett. (HBO)

Peck on set with Josh Hartnett. (HBO)

Peck’s depiction of indigenous communities easily succumbing to white men’s violence is repeated throughout the series.

In a dramatisation of events in colonial Congo, the same white male archetype appears, played still by Hartnett, who shoots a Congolese man in the head for not providing him with enough rubber. Referencing the atrocities Belgian colonisers committed to satiate King Leopold’s greed, the white man orders a young Congolese man to cut off the dead man’s hands while a mass of undifferentiated Congolese stand in the background, in their role as agency-less victims in the history the white man enacts.

There is certainly an argument to be made for centring white men in the histories of violence that accompanied colonisation and a host of other crimes against humanity. The historical record is full of the stories that the series dramatises. Perhaps that is why many reviews of this series have been so generous. People may just appreciate the fact that these crimes have been given cinematic representation.

But by depicting indigenous communities as helpless in the face of white men’s power, Peck reinforces the idea that white men are the only historical actors with any agency to speak of. Moreover, Peck casts white violence as so powerful that any attempts to resist it will result in death.

As a viewer, these scenes were so horrifying I wanted to stop thinking about this history altogether. And that is the danger. The series inundates audiences with images that are so overwhelming it forecloses the possibility of imagining a world without white supremacist violence.

Actor Caisa Ankarsparre in a scene from Exterminate All the Brutes. (HBO)

Actor Caisa Ankarsparre in a scene from Exterminate All the Brutes. (HBO)

For all the problems with what Peck portrays in Exterminate All the Brutes, what he does not say is equally troubling. Throughout the series, Peck’s brassy authoritative voice engulfs the frames, narrating the violence in a dizzying assortment of photographs, videos, animations, illustrations and reenactments. Yet when it comes to images of sexual violence, Peck is curiously silent.

In one part of the series, for example, a disturbing painting titled The Rape of the Negro Girl is showcased with no context. In another, the viewer is shown a collection of photographs of white men sexually exploiting women in various locations in the world, but Peck makes no attempt to explain how sexual assault was used as a weapon of colonisation.

What emerges from Peck’s exhibition of these images is essentially a conversation between men. Peck reduces the women and girls in these images to what might have been the most humiliating experiences of their lives in order to use their subjugation as evidence of white men’s atrocities. This representation of sexual violence reinforces what media scholar Ariella Azoulay has described as the tendency to think of sexual violence as incidental to the histories of colonialism. That is to say, sexual violence is presented as something that just happened during colonialism, instead of being seen as an integral component of the mechanics of colonisation. Not only did Europeans use sexual assault as an instrument of subjugation, the illustrations and photographs Peck displays were often circulated as postcards throughout European metropoles to encourage white men to go to the colonies to enact their sexual fantasies. White women, for their part, used these images to define their piety vis-à-vis the sexual exploitation of women in the colonies.

The ways we tell stories matters just as much as the stories we tell. Peck’s aim in this series is ambitious and laudable. Certainly, the violence that accompanied colonial conquest needs cinematic representation. But it is not enough to simply showcase grisly images of these atrocities. Telling nuanced stories about colonialism isn’t just about telling a story of white violence. It is about decentring the logics of whiteness that makes us present history from the perspective of white men and disregard sexual violence against women of colour.

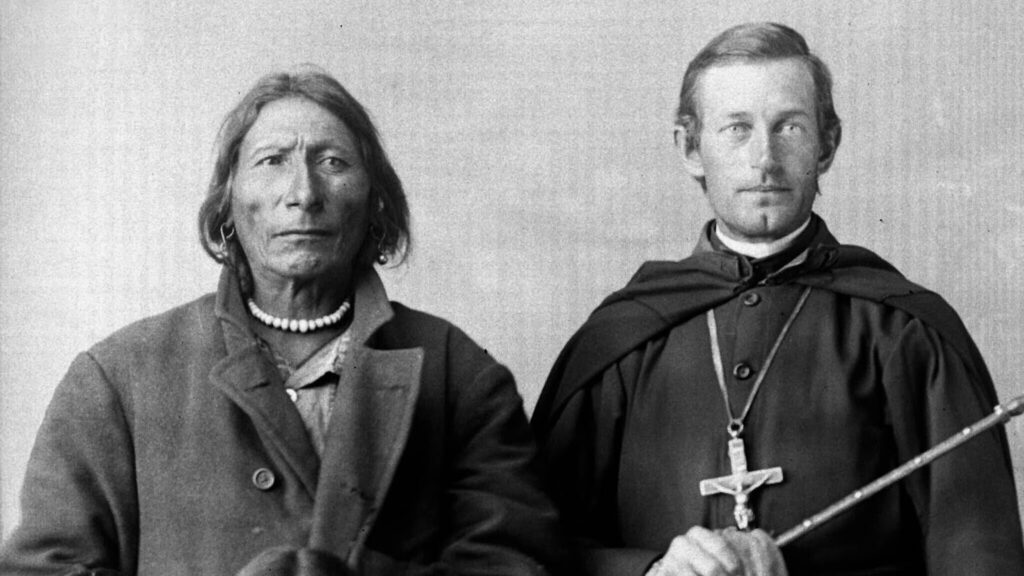

An 1880s photo of Blackfoot leader Long Feather and missionary Father Craft. (Denver Public Library)

An 1880s photo of Blackfoot leader Long Feather and missionary Father Craft. (Denver Public Library)

What we need are well-contextualised cinematic representations of these events that move beyond exhibitions of violence and open up new possibilities for demanding accountability and restitution.

Presenting better histories of colonialism can be found in the rich traditions of resistance in communities throughout the world. From the histories of Native American opposition to Western expansion, to the revolutions against slavery and colonialism in Africa, to the ways women throughout the world continue to foreground conversations that tie the history of colonialism to the disappearance, trafficking, and murder of women in their communities, the historical record and contemporary activism make it clear that white supremacy has always been contested by the people whom it seeks to exterminate. By marginalising these perspectives and centring white men in the series, Peck missed the opportunity to engage with the history of colonialism in a way that empowers viewers to imagine a future in which whiteness is not the locus of power and authority.

This is an edited version of an article first published by africasacountry.com