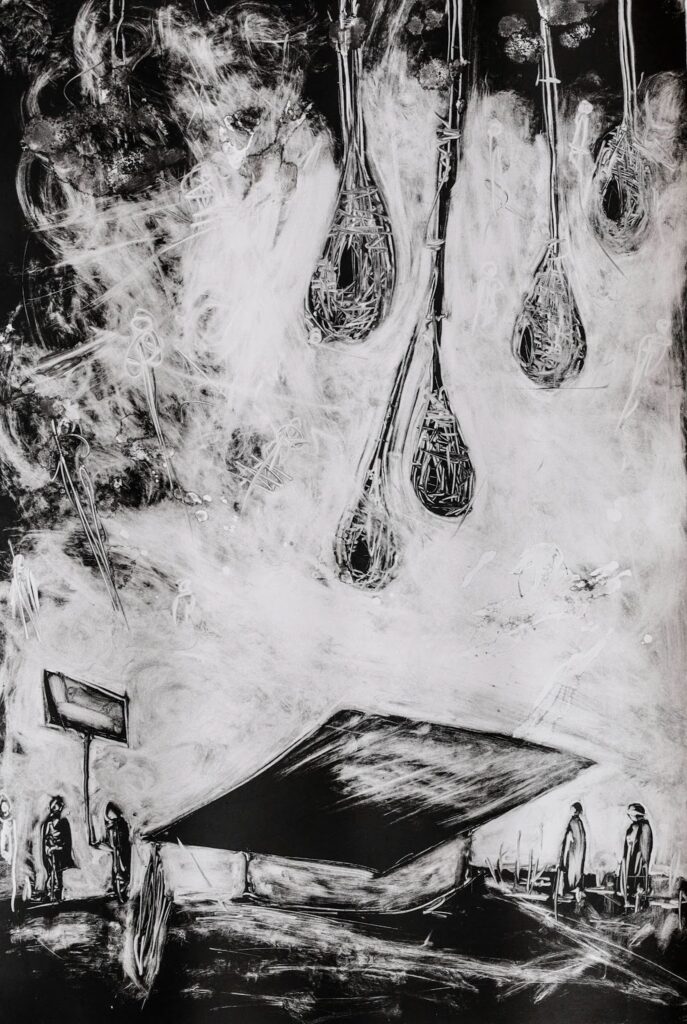

The Man Upstairs, 2021. (Acrylic ink on paper 67 x 101 cm)

Senzo Shabangu’s exhibition Their Humble Abode opened shortly after the suspension of the first round of recent protests in Makhanda.

On 24 May, the taxi associations and the Unemployed People’s Movement initiated a protest against the municipality’s poor service delivery, as seen by the potholed roads, irregular water supply, sewage spills, the failure to provide electricity to informal settlements, and so on. The initial three-day shutdown of Makhanda was suspended after a meeting with a provincial government delegation at the 1820 Settlers National Monument.

What does it mean to draw landscapes and to be an artist at this political moment? Rather than capturing the spectacle, Their Humble Abode responds to the question from a deeper place.

We Are All In Charge for Change, 2021. (Monoprint, 1/1, 101 x 67.5 cm)

We Are All In Charge for Change, 2021. (Monoprint, 1/1, 101 x 67.5 cm)

Their Humble Abode, which opened on 31 May, is Shabangu’s solo exhibition for his two-month residency at Rhodes University’s Raw Spot Gallery, an exhibition that is part of the National Arts Festival taking place this month. This body of work engages with the place of Makhanda in space and time. Visually, one can easily recognise the donkeys, the churches, the nests hanging on a tree outside the Rhodes University library, as well as the graduation cap — the medal that Makhanda offers its young wayfarers from all over the continent.

But Shabangu’s reading goes beyond the visible features of this area of land. A landscape is politicised and historicised through the events taking place in it. In Shabangu’s case, this landscape can also be viewed and experienced through the lens of religion. Audiences are invited to engage with the two altars in this exhibition. You can either light the incense and candles on the church altar covered by a cloth Shabangu brought from his hometown in Mpumalanga, or you can also pick up a stone and place it on isivivane for blessings on your journey.

Shabangu’s work straddles the sacred and the secular spheres, making it profoundly spiritual, but also very political. “I found Makhanda to be a place with churches corner to corner and I was asking myself whether they play a role in helping community members through their own individual struggles, such as the depression caused by being away from home, local government stresses, et cetera?” he told the Mail & Guardian.

The Solomon Nests, 2021. (Acrylic ink on paper 114 x 150 cm)

The Solomon Nests, 2021. (Acrylic ink on paper 114 x 150 cm)

Entering Makhanda for the first time, Shabangu encountered “the man upstairs”. In the drawing of the same name, a man sits far away, high on a mountaintop overlooking the landscape of Makhanda, with its magnificent churches surrounded by people. It speaks to the incongruousness of Makhanda: a small city that boasts more than 40 religious buildings — and an uncharitable municipality.

Red is visually dominant in this work and others in the exhibition. Growing up in a mission school and attending church as a child in Mpumalanga, Shabangu was not allowed to wear any red clothing. It was said to be the colour of the blood of Christ, although the bishop wore a red cassock. Questioning the rule, Shabangu started using the colour red without judgment, an act that is now analogous with interrogating the tension and contradictions of Makhanda.

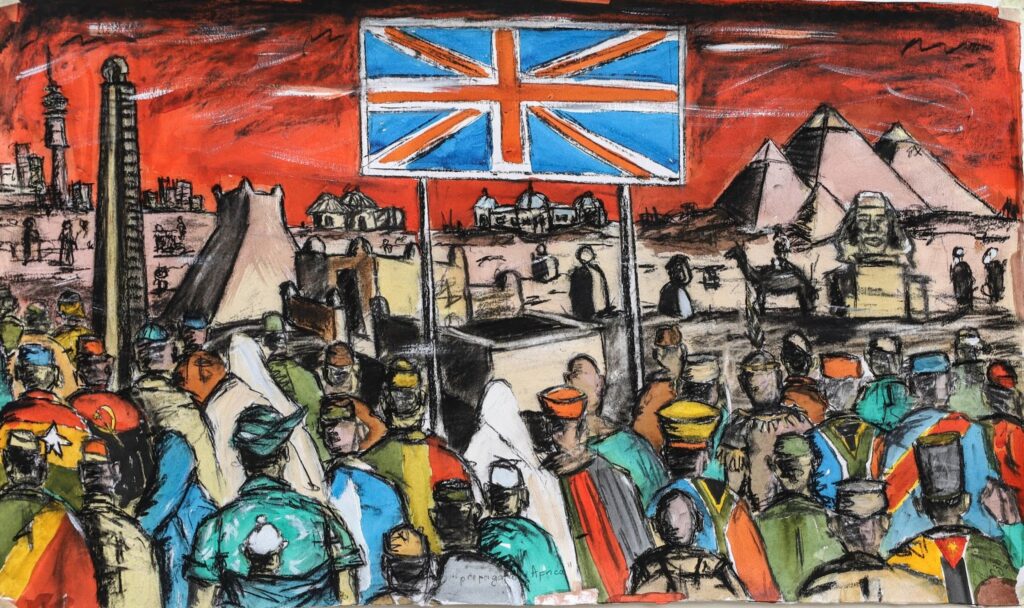

The drawing Propagate Africa has a similar visual structure to The Man Upstairs. In the former, Shabangu travels the continent with his mind’s eye, engaging with the landmarks in different African countries, such as the pyramids in Egypt, the architecture of Timbuktu in Mali, and Goree Island in Senegal. On an imaginary landscape, a group of African children journey in one direction. A Union Jack — the flag of the (once) sprawling empire on which the sun never set — is hanging over the landscape, detachedly yet stable. It is intriguing that only in these two drawings, both of which feature a hand in the sky, are the buildings attached to the ground. The buildings are spatially located and embedded in the landscape’s specific history and reality.

Propagate Africa, 2021. (Acrylic ink on paper 73.5 x 125 cm)

Propagate Africa, 2021. (Acrylic ink on paper 73.5 x 125 cm)

In Shabangu’s works, the people are often migrants, drawing from and resonating with his own experiences of migration. Instead of being abodes that provide a sense of belonging, the distorted, inverted and suspended buildings become a symbol of complex systems that dominate a place, under the eyes of the man upstairs.

In the artwork Their Abode, students in red gowns are likened to the Levites carrying the ark of knowledge. It is a reference to the ark of the covenant famed to house the two tablets (and hence knowledge) bearing the 10 commandments that were given to Moses by God.

Shabangu’s artworks, as in the work We Are All In Charge For Change, go beyond religious iconography to address the human need for hope. His process and his engagement with Makhanda can be metaphorically linked to other life-building processes, such as tapping into the transformative resources already present. Their Humble Abode cultivates the ability to imagine a future and so transcend the present moment.

Shabangu titled a monoprint he created during the protest in Makhanda Iziphithiphithi, which means destruction. The work is visually dramatic and references the strike. Iziphithiphithi is a Zulu hymn with the lyrics, “Iziphithiphithi zalapha mazingangiphazamisi qha! Ngize ngingalulahli ukholo lwam, ngiyofika ngithini le.”

Thinking about a better world as we write this, there is now another protest taking place in Makhanda. The donkeys still wander all over this town, with its roads marred by potholes and residents scarred by poor service delivery.

Raw Spot Gallery in Makhanda is closed because of the lockdown. The exhibition will soon be available digitally.