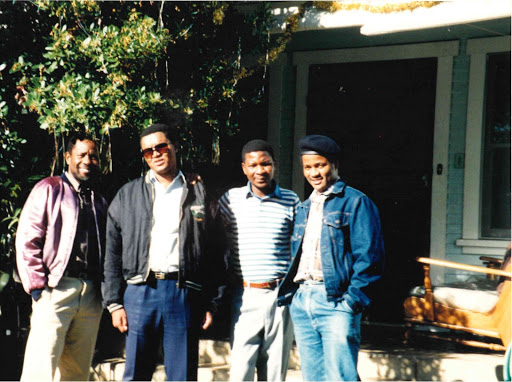

Good times: Joe Nina and collaborator Steve Kekana in March 2020. (Photo: Oupa Bopape)

I

When Thobela FM’s legendary broadcaster Thamagana “Max” Mojapelo cautioned me: “to make sense of Steve Kekana, skip over the usual and head for the hills. There you will hear his voice ululating from space”, I knew it was better to ransack the South African songbook, instead.

These, I smiled, are the miles I’m prepared to walk up the hills. “Steve Kekana lives on in his music.”

As if to illustrate the point, Mojapelo invited me to tune in to one of my favourite radio channels of the 1970s and ’80s, then known as Radio Lebowa, but since the late 1990s going by the moniker Thobela FM.

I caught him when he was preparing for that Saturday evening’s 6pm to 9pm show, the elephant size of it dedicated to Kekana’s discography, and, inevitably, sketches of both pain and place in the Kekana life story.

I tuned in and, for the greater part of the night, was torn between weeping sheets of tears (maybe silent sobs, so as not to wake the entire household up) or just jumping up and doing a solo jitterbug.

Song after song, Mojapelo grabbed this listener by the lapels and threw him against the walls of history. Often, his sonic narrative would be tender, inviting and scooping me onto a magic carpet ride … up, up, and up to the peak of those proverbial hills. Perhaps it was Ga-Mokopane hills, the town where both the broadcaster and his late friend, the musician, grew up.

Kekana was first drawn to guitar as a young buck growing up in Moletlane. He later went on to indulge and express his passionate character about not only the soul of black folk, but also the spiritual wellbeing of all folks under the African skies and beyond, through his numerous gifts: composer, vocalist, later radio anchor, musicians’ rights activist and, ultimately, a practicing advocate and law lecturer. The one gift he will forever be known for is his voice, and technique of voice control.

Tebogo Steve Kekana, known to an intimate circle by his Ndebele totemic name “Tlou” (elephant), came up on the South African musical scene in the late 1970s, although it’s fair to say he bloomed and soared in the 1980s.

Born on 16 September 1958, in Bolahlakgomo, in the Zebediela — ZB! — district of Mokopane, Kekana lost his sight at the age of five. He attended Siloe School for the Blind in the village of Thokgwaneng near Chuenespoort, in present-day Limpopo.

Surrender of the ego: Steve Kekana’s musical chops allowed him to step in and out of vocal ranges, including falsetto, with seamless transition. Photo: Siphiwe Mhlambi

Surrender of the ego: Steve Kekana’s musical chops allowed him to step in and out of vocal ranges, including falsetto, with seamless transition. Photo: Siphiwe Mhlambi

According to Mojapelo’s book, Beyond Memory: Recording the History, Moments and Memories of South African Music, “It was while completing a brief course on switchboard operating in Ga-Rankuwa, then part of the homeland of Bophuthatswana, that Kekana received an invitation from his homeboy Lazarus Kgagudi to join a local band, The Hunters, based in Driekop.”

Other members included the founder, Abram Mojalefa; Ali Malik and Kgagudi himself. His world exploded when the Johannesburg-based talent scout, A&R man and producer Tom Vuma, spotted him among his fellow band members and took him to the big city.

The Johannesburg Kekana stepped into in 1978, was definitely shaped by the earlier century’s gold rush, beautifully reprised in Charles van Onselen’s nonfiction masterpiece, Showdown at the Red Lion, and countless other urban historical lore.

He arrived in the city a year after the brutal murder of Steve Biko, and two years after the country went up in smoke … almost all of it, a result of the apartheid regime’s general dehumanisation of Black folks and, particularly, its police force’s provocation of Soweto high school students.

From the very moment the greenhorn Kekana cut his debut single, a 45rpm disc, Mamsy, at the age of 20, backed by The Pages, he sent a lightning notice.

What is not told nearly enough in the history of South African pop, is that this was also the age in which African male vocalists were reclaiming the vocalist aspect of popular song after the 1950s and 1960s were, by all intents and desires, an era of Black women singers.

Not only was this, then, a male era, the great girl super trio Joy notwithstanding, there seemed to be something in the watering hole at which all these gents from the Reef, right across the Atlantic, quenched their artistic thirst.

For the first time since the first recording of (South) African music using Western technology for commercial purposes, the late 1970s, up to the end of the 1980s, experienced a ground swell of sublimely gifted male falsetto voices globally.

Kekana (centre) in 1982 with Nohlaba Dlomo, Granny Mahlangu, Joyce Ngwenya and Jowie Madiba. (Photo: Gallo Images)

Kekana (centre) in 1982 with Nohlaba Dlomo, Granny Mahlangu, Joyce Ngwenya and Jowie Madiba. (Photo: Gallo Images)

The vocal stylings, then, had nothing to do with their sexuality, although it was in conversation with it. Falsetto technique, best employed in taut but improvisational choruses, as opposed to a full song, was and is still used by male singers to escape the inherent limitations of patriarchal masculinities that would otherwise devalue the emotional quotient the singer aims to share.

We speak here of “patriarchal masculinities” in the commercial music industry, with the hindsight of feminist and queer theory’s persistent reminder of a desired space for non-toxic masculinities; a space in which multiple forms of femininity, and of non-binary multiplicities are available to all manners of Black, African, Beige, Yellow, Asiatic people’s becoming.

These battles were always there, going back to the 1940s where artists such as Dolly Rathebe, and later Miriam Makeba, had to constantly look over their shoulders as gangsters and some of their fellow male band members fought over them, “the molls”, as though they were prize trophies.

II

I find it curious that no other decade outside the soul Sir-cumference of the 1970s to ’80s, has produced the highest concentration of thin-pitched men. Not only did they outsing the “birds”, but they did so with electrifying abandon.

Whereas they entered into the commanding ritual of music-making with their inadequacies and fantasies of power, they often ended up losing themselves into the poetic, music-making realm in which gender — and one’s status anxieties — became, for the duration of a song, obsolete. Barry Gibb, Al Green, Philip Bailey … Steve Kekana, anyone?

This does not even factor in Central, Sahel and Maghreb African, djali town-criers, an Afriscape in which, were it not for the Sufi-Islamic inflections in Baaba Maal’s chords, Papa Wemba’s blend of sing-song weeping and hyena-pitched primal screams would simply float over everyone else’s. As an art form, falsetto offers men an aesthetic escape and return to an inner emotional source within the brief confines of a recorded song.

It is especially challenging mainly because it requires an exacting, disciplined breathing ability. Ultimately, it is the most transparent of vocal styles, simply because it offers listeners a direct peek into a vocalist’s soul and dexterity, with nothing else to cover or make up for its lack of range.

Kekana hardly sung an entire song in that pitch — he was as brilliant a tenor as anyone — his chops allowed him to step in and out of ranges with seamless transition, such that listening to his music almost 40 years later is quite a treat. An unabashed joy.

III

Kekana, who collaborated with the faddishly young, such as Joe Nina, and with the seasoned, such as Nana “Coyote” Motijoane, understood that music making, by design, is derivative of one thing or the other. He understood that borrowing, and surrendering one’s ego, if only to open one’s soul into a receptacle for other artists’ work, just as is practised in literature, design, politics — heck, life! — is what keeps us alive. What keeps us human.

Steve Kekana pictured with Caiphus Semenya and others at a funeral. Photos: (Joe Sefale/Sunday Times)

Steve Kekana pictured with Caiphus Semenya and others at a funeral. Photos: (Joe Sefale/Sunday Times)

It is truly a thing of utter beauty and profound emotion, then, to listen to Kekana’s discography today and be teleported into the future-past with such dazzling force.

Songs such as Mokgotse Wa Hao, Iphupho, Keledi Tsaka and Take Your Love and Keep It, could have just as well been composed and performed in the year 2020, or 2025, for that matter.

The repertoire doesn’t even need tweaking: Kekana’s entire oeuvre contains solid, transnational, funky, and hip notices to audiences, the gods of pop, and yonder. His gospel work was just as celestial. Look for the hymn-like Thapelo, for example, and let us see if the sad young men and women for whom it’s in vogue to rubbish organised religion in favour of a spiritual salvation, or brownie points from fellow hipsters, will not be scampering to church.

His later work, including the albums Love Triangle, Isiphalaphala, and Izifungo, has been treated too shabbily by the ravages of time. Which is not to say all of Steve Kekana’s work or the producers he worked with, notably Tom Vuma, Mally Watson and Eddie Mathiba produced sustainable work every time they stepped into the studio, for that would be nonsensical: all artists have their duds.

In the elastic hip-hop culture and electronic dance music genres (which account for the bulk of all that “pop” entails today), there’s a phenomenon known as the “feature specialist.” In football, this used to be known as the “substitute” star. Steve Kekana was no one’s substitute vocalist. And yet, among his most transcendental work is the gift he shared through his collaborations.

Lewis Hyde writes in his book The Gift: How the Creative Spirit Transforms the World, about the community-making effect of the gift. “We rightly speak of intuition, or of inspiration”, he reminds us, “as a gift … As an artist works, some portion of his creation is bestowed upon him.”

Hyde tells us that “the gift of the inner world”, ergo, music, painting, photography, and so on, “must be accepted as gifts in the outer world if they are to retain their vitality”.

In other words, the spirit of the gift is kept alive by its constant donation. Without sharing, or giving it away without expectation, what’s the use of the gift?

IV

Perhaps more ambitious, vocally, than some of his solo work are the gifts Steve Kekana shared in Sipho Mabuse’s hit song Burn Out. He gifts his fellow artist, and the listener, a blistering two-and-half minutes of musical accessorising.

He wails, ululates, glides, and soars into the ether.

Like a sparrow, the voice darts from one of the song’s tree branches to another, its thin, high pitch poised delicately on the song’s notes. That goes for his duet with Penelope Jane Dunlop, also known as PJ Powers, too. Kekana’s vocal colours, and warmth, emission of love, of light — perhaps a subtext to a heartfelt conviction about a spiritual, personal, and political union within all humanity — in I Feel So Strong is non pareil. It defies musical criticism.

V

Reviewed against the light of history, we have to ask ourselves some questions. Is the confluence of Kekana’s artistic narrative, life as a commercial touring enterprise, his biography too, without blemish? Are we now going to sweep everything under the carpet in accordance with the decorum of refraining from speaking ill of the dead? The man had his short sightedness, an oxymoronic observation if there was one. Although some things were simply beyond his control, some were within his full grasp and choice.

Residents of Zone 5, Pimville, Soweto, still remember waking up to the sound of shattered glass, eyes assailed by the sight of blue flames on 8 December, 1986.

The artist’s house had just been petrol bombed by “comrades” as a score settling for his erroneous participation in the apartheid government’s infamous Info Song project, later to become part of the “Infogate” scandal.

Back in the mid-1980s, the liberation movement, including the internal custodian of the Black Consciousness movement internally, Azapo (the Azanian People’s Organisation), had managed to influence the UN to include a cultural boycott as part of the broader sanctions against the nationalist regime.

The regime sought to undermine the sanctions with a series of political, trade and cultural tactics. One included trading with the Israeli government. But the cultural boycott was much more of a convoluted and complex matter: some artists locally and in the US observed it; others believed music should not be subject to political forces.

When the radical poet and pianist Gil Scott-Heron released a full-on attack on apartheid with the single, What’s the Word from Johannesburg?, other artists such as Elton John, Linda Ronstadt, and Frank Sinatra, aka “Ol’ Blue Eyes”, simply violated it.

In a biography The I in Me, dictated to Sidney Maluleke, Kekana attempts to address the issue. “I was invited to participate in a project spearheaded by songwriter Terry Dempsey and his partner, Dave Pollecut, to participate in the recording of what was understood to be The Peace Song.

“The recording,” he readily admits, “was sponsored by an advertising agency and the Department of Information. Some of the artists included my friend Babsy Mlangeni, Blondie Makhene, and Abigail Khubeka among others.

“But when it was released as Building a Brighter Future, the song caused controversies. Black artists who participated were labelled ‘sell-outs’ but the song had no political lyrics at all. We believed it was meant to forge peace.”

Clearly, Kekana, and his fellow crooners, including white acts such as Lesley Rae Dowling, were victims of wicked propaganda chess moves by Pretoria’s masters of smoke and daggers. He blames “arsonists” sent by “jealous forces”. Frisson coursed through the cultural fraternity like a shooting star. Electrifying!

In the same year the nationalists’ assassin squad was accelerating its killing spree, their masters were trying to negotiate, on the down-low, with Nelson Mandela to renounce violence in exchange for a curtailed freedom.

It is also around this time frame that the very same nationalist mouthpiece, the SABC, took the music of Stevie Wonder, whom Kekana minded himself around, off the airwaves for dedicating his 1985 Grammy award to prisoner 466/64.

Artists were often caught in the middle. Looking back at the era, a more complex reading has emerged. For example, four months before Kekana’s house was gutted, folkloric singer-songwriter Paul Simon released Graceland in the West.

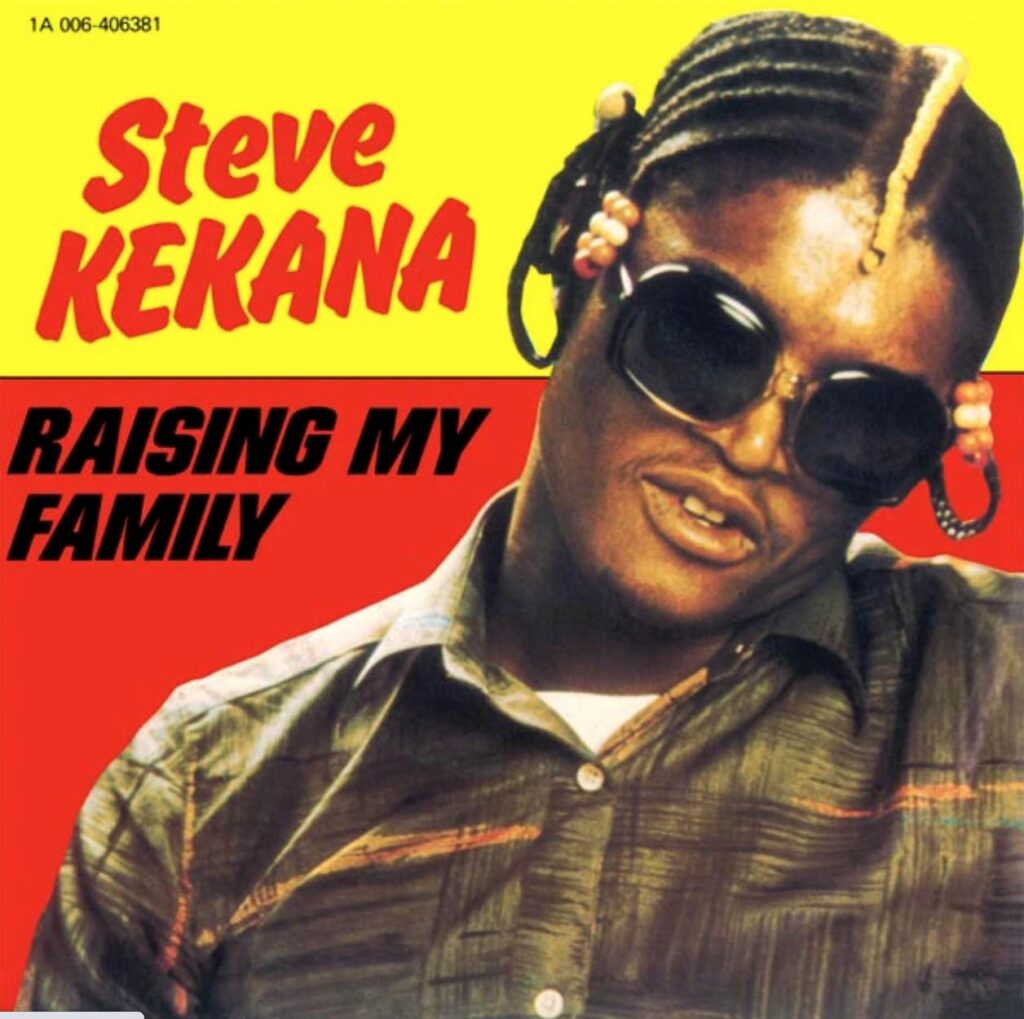

A 1981 album by Steve Kekana produced by Malcolm Watson.

A 1981 album by Steve Kekana produced by Malcolm Watson.

The album was recorded with input from several South African artists including MD Shirinda, Ray Phiri, Bakithi Khumalo, and more. Although the process in which it was recorded was in breach of the cultural boycott, it had the full participation of some of the fiercest anti-apartheid global icons, including Miriam Makeba and jazz man Hugh Masekela.

In 2015, the late Ray Phiri confessed to me: “I would do it again.” Graceland, according to Phiri “was the best thing to happen to South African music. It placed us on the map.”

Four months after its release, Kekana’s house was up in flames, for a different project, but the same breach. Who should artists listen to? Aren’t they the ultimate conscience of society?

VI

The mid-1980s, turned out, in true Dickensian adage, to be “the best and worst of times” for Kekana. Perhaps then, the bluest reckoning of Kekana’s working life happened a year before Infogate.

Kekana, a massively popular artist in the “frontline states”, and the “protectorate” of Lesotho, was scheduled to perform in Maseru. But in what was almost a repeat, although at a much more tragic scale, of the Rolling Stones performance at Altamont, San Francisco, a stampede occurred.

Hundreds of revellers died in Maseru during Kekana’s performance, some injured for life. The “Maseru Disaster” as it became known, gutted him like nothing before.

Kekana returned to the studio the same year and recorded a song, Koduo Ya Maseru, dedicated to the country and its citizens, with all royalties donated to a disaster fund to assist families. Maseru was not within his control. It sliced his spirit apart nonetheless.

VII

Although I have never watched Steve Kekana’s concert live, beyond the pixilated, and grainy television screens in my village growing up, I was shocked at seeing him in the flesh one balmy summer night in 2009.

We had been house visitors of the late Busi Mhlongo at her Innes Road home in Morningside, eThekwini. Her apartment was on the third floor. The door was wide open. Mhlongo, myself and a friend had just finished cleaning.

The mood in the lounge snapped and sizzled with gay abandon. We were all dancing in a circle to Nomeva, a Welcome Duru composition reprised in Mhlongo’s album, Freedom, when in poured Kekana, also dancing and laughing, with his friend Joe Nina. With nary a greeting, they joined the circle and boogied down. From which spaceship did this gifted pair just alight? We never asked; they never volunteered it. I froze. The Zulu rock queen tore into laughter.

This is to say I only defrosted now, more than a decade later, rushing to drop this full stop.

Bongani Madondo is the editor of I’m Not Your Weekend Special: Portraits on the Art, Life, Style & Politics of Brenda Fassie. He is the author of several essay liner notes for Busi Mhlongo’s DVDs and the album, Amakholwa: The Believers.

Special thanks to Sydney “Fetsie” Maluleke and Thamagana “Max” Mojapelo for assistance with their personal archives