Shattered beauty: The exhibition, disquieting domesticities, vestiges of violence, is unnerving but does not descend into trauma porn. (Photos: Michael Hall)

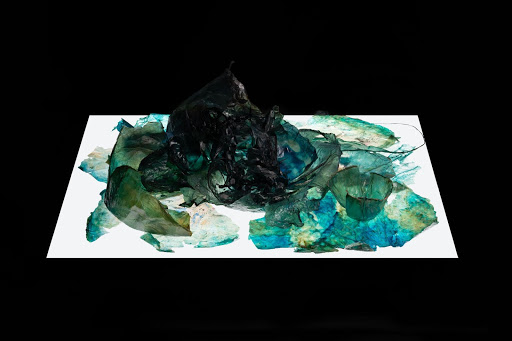

From a distance, Leora Farber’s installation at Cape Town’s Iziko South African National Gallery resembles a luxury display cave of gems — pretty, shiny things — whose multi-hued allure is enhanced by the black backdrop against which they seem to float. But as one enters this silent space, ostensibly without walls — almost like a black box performance space — the sense of disorientation becomes acute. And as the objects loom closer, their pristine surfaces are irrevocably shattered. Shred. Shed.

Words matter immensely in Farber’s work and not merely in terms of the alliterative, double entendre of the installation title: disquieting domesticities, vestiges of violence.

The range and intricacy of her artistic vocabulary — whether shaped from wax, found clothing or medical instruments —- has always been astounding, uncompromising and, yes, sometimes didactic. If we follow the trajectory of Farber’s auspicious artistic and academic career from the 1990s to the present, her imagery — multilayered, dazzling and dizzying in its detail — has often exuded a sense of controlled spillage.

In fact, control has played a major role in Farber’s oeuvre. Her titles, imagery, methods and materials have often served as conceptual guide tracks for the viewers, gently but firmly navigating us towards a tailored reading of her work that, although enriching, inadvertently discourages personalised projection. Her imagery has certainly evoked visceral responses, like disquiet, discomfort — even flinching recoil — particularly in the case of her carpaccio-thin slivers of skin, clinically displayed in medical cabinets; or her performance videos of cosmetic surgery procedures that expose the female body’s disfiguration in the pursuit of perfection.

Bioart: Leora Farber’s artwork is a fusion of science and art. The objects morph and mutate as the living material reacts organically

Bioart: Leora Farber’s artwork is a fusion of science and art. The objects morph and mutate as the living material reacts organically

But as viewers, we become so immersed in deconstructing the references and recurring tropes — there is always a profusion of allusions in Farber’s art — that we sometimes forego the more basic emotional responses generated by great art. When confronted by a Farber masterwork, our response is primarily intellectual. We explore and acknowledge her brilliance, without necessarily bursting into tears.

Not so, with this installation.

Part of the power and poignancy of disquieting domesticities, vestiges of violence derives from Farber’s choice of medium. For several years she has experimented with bioart — an intricate fusion of artistic and scientific forms, using live tissue, bacteria and symbiotic cultures like yeast that react organically with the atmosphere. Given Farber’s ongoing fixation with procedures that rip apart and reshape representations, her foray into bioart constitutes a logical and, perhaps, inevitable component of an ongoing journey.

But unlike much of her previous output, in this installation she has relinquished control of her material, leaving it to morph, mutate, shape or shrink as the laws of nature dictate. Simply put, she has allowed this material to breathe and assume a life (or death) of its own, without prescribing or predicting its form and, consequently, its content. Letting go and simply letting be has proven immensely liberating, particularly for an artist renowned for her fastidious mastery of material.

On one level, Farber’s imagery is located within the history of colonialism and hegemonies borne of violence. This is a recurring refrain in her oeuvre and in this installation references abound to styles of bone china and porcelain, such as Chinese, English and Delft blue. These are ideologically loaded patterns emulated by settler colonies that still adorn the mantelpieces of many homes in South Africa.

It is the more intimate evocations of “displacement” in this installation that are so unnerving, triggering responses that were possibly unintended by the artist

It is the more intimate evocations of “displacement” in this installation that are so unnerving, triggering responses that were possibly unintended by the artist

Displayed as aspirational status symbols or merely for decoration, their pretty surfaces are decontextualised from a history of dispossession that still characterises the contemporary African continent. The clues are present in the objects themselves, but content is cloaked by the material that mutates in unpredictable ways. We can choose to deconstruct the layers on the most accessible of levels or venture into more subliminal, personalised and skinless terrain.

There are a plethora of associations and emotions unleashed by the objects on display: fragility, atrophy, impermanence and states of otherness. But it is the more intimate evocations of “displacement” in this installation that are so unnerving, triggering responses that were possibly unintended by Farber but which resound within the tumultuous context of contemporary life. Gender-based violence and domestic abuse have been coined and recoined with horrifying regularity as South Africa’s shadow pandemic and shameful national brand. Daily we consume, in lurid, literal detail, the images and narratives of intimate-partner violence.

But despite the unavoidable associations of the installation title, Farber’s imagery does not succumb to trauma porn, providing instead an understated, subtle, yet devastating evocation of domestic disintegration. Her surfaces are strewn with homely paraphernalia like crockery and cutlery. From afar, they appear intact. But up close and uncomfortably personal, the surface trappings of domestic order crumble. They are buckled and broken — shards without sharp edges — and they cannot be glued back together.

Up close, glorious hues of crimson, magenta, burgundy that seem to glimmer from afar transmogrify into stained surfaces, resembling blood spatter. Brilliant indigos and violets become bruised, torn skin or scraps. Up close, the glow has dissipated, and the installation reduced to a shroud, filled with haunted detritus. Is it an abandoned crime scene strewn with disintegrating forensic evidence? Or a shrine to memento mori, signifying possibly the shattering of domestic dreams? Or a silent lament to the decomposition of nationhood built on the backbone of conquest?

Up close, the glow has dissipated, and the installation reduced to a shroud, filled with haunted detritus

Up close, the glow has dissipated, and the installation reduced to a shroud, filled with haunted detritus

Yet there are also suggestions of redemption, as in the shedding of skin, signifying little deaths and heralding the hope of rebirth.

Too much projection? Perhaps. But therein lies the richness of an installation described by cultural analyst, writer and educator Ashraf Jamal as “achingly beautiful”. Through the power of its haunting beauty and pain, disquieting domesticities, vestiges of violence touches us in that ineffable place reserved for great art, in which a gasp and a sob are indistinguishable.