‘Comrade Editor’: Gwen Lister pictured in the offices of The Windhoek Advertiser. (Photo: Courtesy of Gwen Lister/Tafelberg)

A few years ago when I was helping my mother to organise her library, one of the sections

we decided on was “African nonfiction”. We never had any intention of going full-on Dewey Decimal, but we chose not to observe even basic distinctions, such as shelving politics and history separately to biography and memoir. Our rationale was that so much of the writing focused on individuals — from biographies of well-known figures to more personal memoirs of childhood — was deeply tied to the recent history and politics of our continent.

Gwen Lister’s Comrade Editor: On Life, Journalism and the Birth of a Nation fits neatly into this categorisation. Over almost 400 pages it chronicles the years leading up to Namibia’s independence, and beyond, in tandem with Lister’s development as a journalist — and with a scattering of personal anecdotes and reflections woven throughout.

Lister arrived in Namibia (then South-West Africa) in 1975, after finishing university in Cape Town, and has stayed there ever since. She cut her teeth at The Windhoek Advertiser, edited by the incorrigible Hannes Smit (“Smittie”), before going on to found The Observer with him in 1978, and then The Namibian in 1985.

What these events had in common was Lister’s determination to live by her principles. She originally decided to move to Namibia because she wanted to rise to the challenge of confronting apartheid and reckoned “change must come there sooner than in South Africa itself”. Down the line, Lister left The Windhoek Advertiser, together with Smittie and his secretary, when the paper was bought by a businessman believed to be a front for the Democratic Turnhalle Alliance political party. And she walked out of The Observer in turn — together with nine other staff members — when new management demanded a more “moderate” political line so as to attract advertising.

Those principles — a deep commitment to activism, journalistic integrity and editorial independence — have informed Lister’s life and work. She makes no bones about combining journalism with activism, but has a more nuanced take than suggested by the reductive labelling of her critics, some of whom perceived her (and The Namibian) as being pro-Swapo before independence and then anti-Swapo when the liberation movement ascended to power.

“Of course, that’s not true. We’ve always been independent from the get-go,” she tells me over Zoom. “[Our] sort of natural alliance, if you could call it that, with the liberation movement prior to independence really was a result of the fact that when we set the newspaper [The Namibian] up, we did so also to clearly support the aims of bringing about an internationally recognised settlement for Namibia.”

It’s easy enough to understand why Lister would’ve had her detractors in the 1980s, daring as she did to believe in a free Namibia and advocate for it in her newspaper, while maintaining that Swapo would necessarily be part of that equation. (The Nambian’s first posters boldly proclaimed “INDEPENDENCE IS COMING”.)

But it’s a mark of her editorial integrity that Lister and The Namibian did not let up on holding power to account after independence, earning Swapo’s ire for critical reporting that resulted in a government advertising ban in 2000, lifted only a decade later. Back in the day, one of Lister’s reporters, Chris Shipanga, gave her the moniker “Comrade Editor”, but in the final analysis, the emphasis is always on “editor”, rather than “comrade”.

This independence is also evident in the manner in which Lister structured the ownership of The Namibian, through the Namibia Media Trust. “I felt very strongly that because we had started out with donor funds … we had a kind of a sacred trust to really set the paper up in such a way that no individual would ever benefit directly if the paper became commercially viable, as indeed it did,” she says.

“And so we set it up as a trust; any dividends that came after staff had been looked after, and new equipment bought and things like that, would go towards promoting the ideals of [an] independent press and press freedom in general. And that is actually what happened.

“I’m very proud of that because, if you look at newspaper ownership, not only in Africa, but worldwide, there are very few newspapers that are not owned by individuals who are trying to make money from them.”

But more about her book. It doesn’t fit neatly into any single category, and different strands will probably resonate with different readers. For me, the historical narrative was a decent primer to the Namibian politics of the period it covers; others with more background in the topic may have their quibbles.

What I’m struck by most is how, although the book is full of anecdotes, in the more personal moments, Lister’s verve in real life doesn’t quite translate to the page. It feels a little dispassionate, as if she’s reporting on her own life, rather than recounting it.

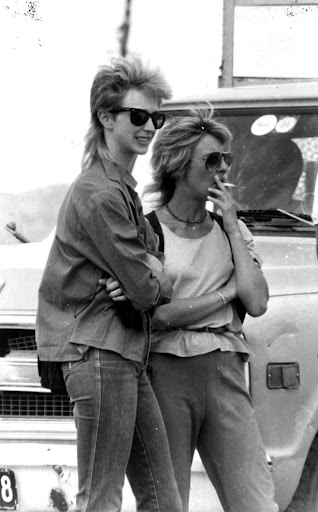

Gwen Lister and Sue Cullinan covering a SWAPO rally in Katutura in 1986. (Photo: Courtesy of Gwen Lister/Tafelberg)

Gwen Lister and Sue Cullinan covering a SWAPO rally in Katutura in 1986. (Photo: Courtesy of Gwen Lister/Tafelberg)

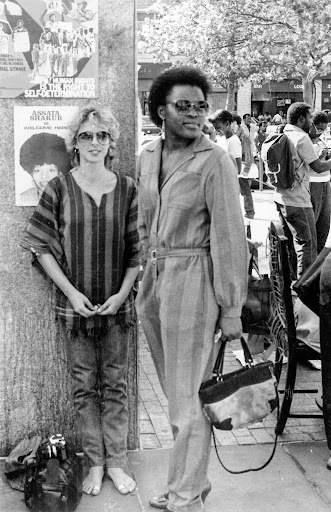

Gwen Lister with Kakena Nagula at a protest in New York. (Photo: Courtesy of Gwen Lister/Tafelberg)

Gwen Lister with Kakena Nagula at a protest in New York. (Photo: Courtesy of Gwen Lister/Tafelberg)

Gwen Lister with journalist Chris Shipanga in 1985. (Photo: Courtesy of Gwen Lister/Tafelberg)

Gwen Lister with journalist Chris Shipanga in 1985. (Photo: Courtesy of Gwen Lister/Tafelberg)

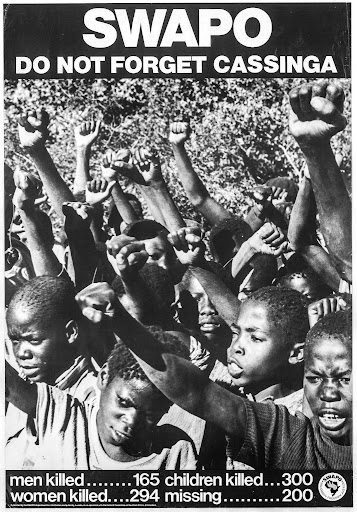

A Swapo poster commemorating the Cassinga massacre. (Image courtesy of Gwen Lister/Tafelberg)

A Swapo poster commemorating the Cassinga massacre. (Image courtesy of Gwen Lister/Tafelberg)

“You know, the last thing I wanted to do was come across as this arrogant sort of ‘I specialist’, as I call it,” Lister says.

Later, in a follow-up email, she elaborates. “It was already difficult to weave the different narratives of Gwen the person, a life in journalism and a country coming into being, and more about me would have tipped the balance.”

That said, my observation about the dispassionate prose is more about style than content. “When I go into those private parts, [there probably is] a certain distance between me and what I’m saying. But all is truthful and all is honest,” Lister says.

There are moments of vulnerability too, as when she opens up about what we may now describe as imposter syndrome.

“I was bold, but also insecure, with nails bitten to the quick. It took a conscious effort to overcome my feelings of self-doubt,” she writes. “Decades later, while others routinely saw me as self-confident and even fearless, I was still beset by diffidence and apprehension, shrinking in the face of the compliments that occasionally came my way.”

This conscious effort was necessary, not only in terms of personal and professional growth, but because Lister was a woman doing “a job meant for a man” in her hard news reporting. “Women belong barefoot in the kitchen or naked in bed,” Smittie yelled at Lister during her Windhoek Advertiser job interview. (I say interview, but from the description in the book, it might more accurately be classed as a pub crawl, at least on his part.)

How did Lister cope in this environment? She talks about the “concrete ceiling” of the 1970s; “if things have improved marginally, it is now glass rather than concrete”, she notes.

“I think you toughen up to such an extent, or you are forced to, that you develop quite a thick skin, and you don’t sweat the small stuff,” she says. “It gave me such a thick skin that there were times I forgot I was a woman.”

One of my favourite anecdotes in the book occurs when Lister was reporting on a Swapo rally in Katutura. The event was heavily policed and, when the police noted her arrival, her friend heard one of them saying: “Hier kom Lister.” I don’t, of course, know the tone in which the words were spoken, but, like her friend who still teases her with this sentence, it makes me smile; the phrase unwittingly encapsulates Lister’s energy and determination.

Although Lister handed over the editorship of The Namibian in 2011, she chairs the Namibia Media Trust and “still has an interest in what is happening” — these days in terms of good governance, rather than editorial content.

Even as she approaches 70, Lister continues to take on new challenges (such as hosting the Namibia Media Trust Foundation’s FreeSpeak podcast), forever breaking through that ceiling, whether concrete or glass. “I kind of feel as though I should belong in the newsroom; I should still be out there doing stories,” she says. This is the kind of calling that doesn’t fade with age.

As Lister observes towards the end of our interview, “Journalism really, in its best form, is public service.” Most journalists like to believe we subscribe to such a principle. But for Lister, it’s not just a pithy phrase — she has lived by it.