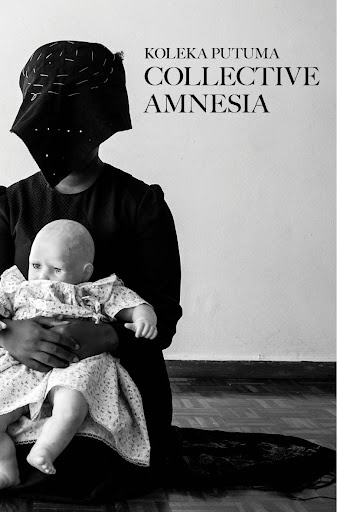

Dynamism: Koleka Putuma (above), the author of Hullo, Bu-bye, Koko, Come In and Collective Amnesia. Photo: Jarryd Kleinhans

This draft begins with a disco of friends in discourse. The conversation is centered around influential individuals in Evaton, one of the oldest townships in the Vaal Triangle. The friends dance at length about how the local government needs to do more in celebrating its icons by spotlighting their names and paying homage to their home.

One suggests that a particular school be renamed Mbuyiseni Ndlozi HS, ‘because who is it named after anyway?’ Jolted by this suggestion, another takes to Google in discord with the search, ‘Who is Maxeke Secondary School named after?’ The result startles the lot: ‘Charlotte Mannya Maxeke, the first South African black woman to graduate with a university degree and founder of the now Women’s League of the African National Congress, founded the school in 1950.’

Now, “come, let us begin: writing it as it was, as it is, is how we exhume the bodies and give them names.” — Hullo, Bu-Bye, Koko, Come In.

History rumours that when settlers colonise a country, one of the first acts they put into motion is the mounting of their own names, from highway to street to landmark; theirs is to make certain that their work is universal; that they render the names of the natives extinct — “in another draft, disappear is substituted with erasure” — they centre their own narrative in the natives, too.

This mission extends across generations; its custodians understand its importance, and preserve it past their “loss of power” through all sorts of protests. If you are a native you will say their names; they will become “little wildfires in your mouth” until you “teach your saliva how to soak and extinguish fire”. You will chant Pretoria, Grahamstown, Bree (Street) and be forbidden to even whisper Tshwane, Makhanda, Lillian Ngoyi (Street). They will teach you to “be careful to hear and spell each of their names correctly, while they mispronounce and mutilate yours”.

They understand the mandate: YOU WILL SAY THEIR NAMES! — a mandate award-winning poet, playwright, and theatre practitioner, Koleka Putuma invites us to follow in Hullo, Bu-Bye, Koko, Come In. A sophomore to her internationally acclaimed bestseller, Collective Amnesia, her new volume is an exceptional excavation and archival treasure, a masterclass in line with the discourse we have seen recently from Dr Athambile Masola and Panashe Chigumadzi, of both the history and the present of black women and queerness; a murky mirror as it were, incessantly demanding of the reader to wipe sleeve first; carelessly or perhaps carefully, to experience themselves. Whether as victim or culprit, you find yourself in these pages.

In the dynamism of her writing, Putuma is speaking and re-speaking, continuously concerned with sight and being swallowed; site and sinking. Sometimes emotional and at times wryly stoic, her voice reads deliberately soft when the words are hard, and the work feels like a chorus, a kind of sing-song chorus; sometimes equanimous, and at times a ruckus. Whether you are the one who’s been backstage or on stage or in the audience or deciding the curtain call, you will find yourself in these pages, and you will learn about these women, and you will know of their pain, and you will remember their names.

“It has become a show, showing up here callous bone and no skin. It has become running vulnerable and unarmed. It has become surgery, spilling here. It has become ritual standing here, splitting insides for you to grab. To microscope. To pick and poke. To make sacrificial. To make Venus. To make Krotoa. To make Eunice Waymon. To make Megan Thee Stallion. To make Anarcha. To make Bometa. To make Vatiswa Ndara. To make Heed. To make Jadine. To make Winnie after the death of stompie. To make Winnie after the death of Winnie. To make Sula. To make Pecola. To make Kwezi during & after the trial. To make Sorrow. To make Beloved. To make token.”

Putuma meticulously undoes the erasure of the black women who became invisible even to themselves in the spotlight, and those forgotten; the women who took their own lives and those whose lives were taken. She looks at the life and “death [backspace] suicide” of May-Ayim, notes Ingrid Jonker “walking into the sea”, Deborah Digges “jumping from the upper level of a stadium”; she notes 12 other names, and Khensani Maseko, and Shoki Mokgopa, and Nichume Siwundla, and Thapelo Lehuleri, and “the disappearances that go on record. The disappearances that do not go on record as sirens or signals. Then the disappearances that go on record as resignation and sick leave.” She notes the persistence of mental health and its effects, and questions its cause.

She layers quotes from Jasmine Mans, Makhadzi, Tsitsi Dangarembga, Lorraine Hansberry, Ntozake Shange, Nina Simone, Thuli Madonsela, Audre Lorde, Ama Ata Aidoo, Luisah Teish, Miriam Makeba, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, and Brenda Fassie, who becomes the motif unapologetically gyrating across the pages; black girls are beautifully represented.

It has been more than three months since its release, but very little noise has been made about Hullo, Bu-Bye, Koko, Come In (Manyano Media)

It has been more than three months since its release, but very little noise has been made about Hullo, Bu-Bye, Koko, Come In (Manyano Media)

In a loud laud, Putuma chants also the names and achievements of 22 black women who “built this country with their movements, too”; adds an infinity of “Ntombi”, this being all the black grandmothers and their grandmothers and their great grandmothers; and with felicitous phonetic she forgets not the “Moghels”. The black girls are thoroughly represented.

“The Moghels… with nuanced praxis… lens so expensive they don’t know how to archive them, when they insist on making themselves visible/undead.”

Hullo, Bu-Bye, Koko, Come In is published by Putuma’s multimedia creative company, Manyano Media; it has been more than three months since its release, but very little noise about it, compared to her debut, which was initially published by Uhlanga Press until she bought back the rights. This poses the question of whether the lack of noise is in itself a form of erasure; a sinister irony given the nature of the work. Whatever the answer, Putuma bought the expensive lens, archived and made visible the Moghel across the ages, and what is left of us is to drive on Charlotte Maxeke Street knowing the power behind the name; ours is to SAY THEIR NAMES.

[CMD+N]

Addendum:

There is a somewhat scanty stain that sits on the success of Putuma’s debut, this being the question of its poetic prowess.

One critic, Unathi Slasha, wrote, “Most of the poems in Collective Amnesia border on the banal, w/out the urge or perceptiveness to investigate, or explore the inner workings of the subject of probe, some read like diary entries, at times, a collection of facts comes, arranged and ordered in the ordinary way of conventional stanza-making. Facts remain stale and still and refuse to come alive on the page.” This is a sentiment that lurks sotto voce, perhaps not as brusque, in plenty a poetry corner.

Let us assume, perchance, that Slasha’s sentiment bore some kind of merit. The subsequent question would then be: Has there been any improvement in the poetry with the sophomore? The answer to which, in my opinion, is: Definitely in the perceptiveness to investigate, or explore the inner workings of the subject of probe, but barely in the crafting of this investigation and exploration into formidable verse.

Putuma discursively advances the themes she explored in her debut, and dexterously “dances with archives, names, lives, legacies of in/visibility and memory.” Alas, the dances with poetry are few and far between. The rhetoric and prose loosely draped in return keys posing as enjambment, and free from all constraints of standard punctuation, arbitrarily bump into beautiful moments of poetry, but as Wislawa Szymborska puts it, “Prose will stay prose, no matter how hard you work to break your sentences into lines of verse.”

Collective Amnesia, Koleka Putuma’s debut volume is an internationally acclaimed bestseller. (Manyano Media)

Collective Amnesia, Koleka Putuma’s debut volume is an internationally acclaimed bestseller. (Manyano Media)

Let’s take the piece, who die singing Igqira lendlela, for instance:

“for the ones buried under elaborate tombstones that cost more than the money they left behind

a family too ashamed to bury publicly

a celebrity who died lonely and in debt

nothing to show for being loved …

your gallerist still makes euros from your art

while your children piece together your belongings

in the shack you left behind.”

Now, backspace the return key and replace it with a comma here, a semicolon there and a period here and there, then read the passage again. There is no discovery, no care for aesthetic and elemental detail, only a retelling of what is already known in a way that it has been heard countless times before. I imagine any sensible reader’s thinking to be, “This is powerful, but where is the poetry?”

What is poetry if not creation, if not the viewing of something known anew as if experiencing it for the very first time; the morphing of words into images, arranging them in a manner that speaks a new vision; the creative crafting of language, through the use of narrative, image and rhythm, to produce powerful and clear impressions on the senses? Putuma is a poet — she understands this; one would then expect this understanding to augur a corresponding implementation, which it does, at times.

Putuma has displayed this understanding in a myriad of her past work, and does also in this collection with poems like, this is not mine, you ask too many questions, and painstakingly in a habit mistaken for savior. It is the presence of such poems that exposes the inconsistency of the poetry in the collection in its entirety.

In the second chapter, “BU-BYE”, Putuma writes:

i am

a habit mistaken for savior

everything is burning again

the suicide attempt is on the other side of the telephone

gripping hem and ankles

the smoke strangles me before I get there…

i am an asthmatic addicted to arson

i stand guard outside her body

while she disappears for the both of us […]”

And proceeds in the last chapter, “COME IN” to write:

in my first year in varsity

i mumbled camagu for the first time

more as a question mark than an amen

my clan names toss themselves

little wildfires in my mouth

i spend the rest of my degree

telling them you belong here…

i spend the rest of my degree

teaching my

saliva how to soak and extinguish fire […]”

Powerful and vivid images for powerful and consuming poems. Alas, Putuma collapses the latter poem with a lack of brevity, terseness, and attention to detail. She extinguishes the image with a careless bathos; further down the piece saliva is now licking drink-o-pop powder and fire burning scalps with soft-n-free. As a poem it reads like a draft before the final draft, contra to the former. These two poems, along with who die singing Igqira lendlela, are a taut exhibit of the irregularities interspersed in these pages.

As a collection of poems, Hullo, Bu-Bye, Koko, Come In is a lacklustre body of work; however, as a nonfiction literary project, it is among plenty a paean to black women, queerness and blackness, and a palimpsest of their lives — the writing itself is monumental, a shaper of space and a marker of time; its implements memorials to their user. Its intent was beautifully and subtly and strongly carried out; it is a coherent and innovative project, writing with the pieces of bone it is holding so gently.

Certain parts of this article borrow the stylistic elements of Putuma’s Hullo, Bu-Bye, Koko, Come In