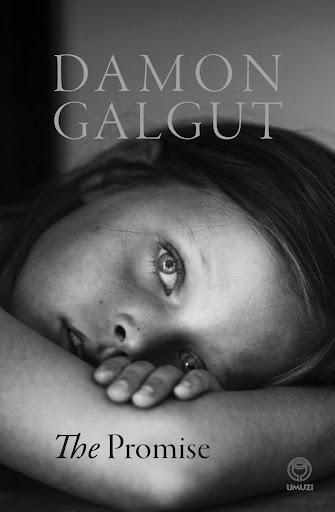

A brief epic: South African author Damon Galgut won the 2021 Booker Prize for Fiction. He has been shortlisted on two previous occasions — in 2003 and 2010 — and won it with his ninth book, The Promise. Photo: Tolga Akmen/AFP/Getty Images

Damon Galgut and Imraan Coovadia spoke in early December, teasing out the Booker Prize-winning book’s themes, references and structure. The conversation has been edited for brevity

Imraan Coovadia: I wanted to start with your views about mathematics. Someone in The Promise says, there’s no need for mathematics because every human being is an individual. At the same time, in a particular passage late in the novel, the Swarts describe themselves as a typical white South African family. What’s your view? Can we make classes or is everything individual?

Damon Galgut: I hadn’t thought about it in as much fine detail as you clearly have. That paragraph was one I almost scratched out. The tricky bit to this book was transitioning between one perspective and another, which was also the most fun part. That was one particular transition where I was going from something incredibly intimate, to, well, to another intimate scene, but I thought a good bridge might be to pull back into something as cold as mathematics where everything is reduced to numbers. And in fact, for some reason, that particular paragraph seems to have struck a lot of people.

The thing that everyone said to me before I read the book was, you know, it violates all the typical rules about narrative perspective, moving from one character to another and then to the next. And when I read it, I didn’t find it difficult to read. You probably looked at some other experiments in narrative transitions, say, Sartre’s The Reprieve or Dos Passos’s Manhattan Transfer.

I worked quite hard for the transitions not to be confusing, but all one’s writerly instincts resist those kinds of narrative bumps where you’re suddenly displaced from where you were. At the same time, there’s a frisson that goes with being able to set one perspective, very, very bluntly or extremely against another one in quite swift succession. I guess the worry with this particular mathematical transition is that it goes from something that’s quite human and close up to something that’s quite cold. The word Fourie [Botha, Umuzi’s editor] used, not about that particular moment, but in general, is “cruel”. I assume he’s referring to those moments when the perspective loses a human lens and becomes something far more detached. The difficulty in a bump like that isn’t in the logic but in the tone. As you know, very well, one of the many tricks that novelists use is to draw you in with a point of view that is humanistic. So maybe it’s cruel to bump the reader into a new perspective, out of the human skin … looking at us from somewhere else.

Damon Galgut’s The Promise is his ninth novel, and his first in seven years

Damon Galgut’s The Promise is his ninth novel, and his first in seven years

A view from nowhere or faraway … There’s one lovely sentence about someone worrying she’s going to break open like a tomato. There’s another moment I wanted to ask about. This is a mixed family, Jewish and Afrikaans. But there’s not a lot of what people might call Jewish humour in the book. At a certain point one of the sisters worries that her brother isn’t in the casket at his funeral. Someone else rebukes: who else’s brother would be in the casket? I thought that was as close as the style came to a certain kind of Jewish joke.

Someone pointed out to me the other night, there was a review in the Jerusalem Post: “Book about Jewish mothers wins the Booker Prize,” which strikes me as a very kind of Jewish perspective. I didn’t subdivide the humour into particular categories although I have a partly Jewish background. I wasn’t sufficiently steeped in the Jewish approach to the world to absorb idiosyncratically Jewish humour. The elements that went into the family went in for two reasons. I was trying to write about white South Africa, which is very jumbled. So I was drawing somewhat on my own background: my father’s Jewish, my mother converted to Judaism, yet didn’t raise us that way. She divorced my father, married a Calvinist Afrikaans man, and we suddenly had a dose of that. My mother’s very eastward-leaning in her religious inclination, so I had a dose of Cape Town New Age before it was fashionable. I was giving the same mix from which I feel I was concocted. In another way, if you’ve decided to construct your book around funerals, it would be dull to repeat the same service or the same particular religious sentiments each time. So simply from the point of view of varying the fare, I thought it would be more entertaining for me and for people who read the book to have different sort of religious inflections.

You could have called the book Four Funerals and a … I’m trying to think if there’s a wedding somewhere.

There’s no wedding. Weddings and funerals seem to be those family affairs that bring people together from distant places. But I think funerals won in this case, because for me, the book is about time and the passage of time. And the final terminus of that journey is death. So it tends to be on my mind quite a lot.

Then comes reincarnation. The other text someone might connect this to is EM Forster’s Howard’s End, considering the question of the legacy of a house, given by a woman, and resisted by conservative forces. I read it thinking it might be Damon’s view of Howard’s End. But it isn’t that at all. It’s a story about the destruction of a family. Why is that the story you wanted to tell?

I can safely say that in no conscious way was EM Forster in my thinking. And yet when an early review picked up on that it didn’t displease me. I think it’s plausible that writers carry stuff unconsciously from one book to another. We consciously try to start afresh each time but there are clearly threads and seeds one carries over from one book to another. Forster’s book is working with the idea of a house as a place of belonging and refuge. I think South Africa being what it is, the notion of any property being a place of sanctuary is open to question in multiple ways. The decline of the family was not consciously part of my project. I got the original idea for this particular book from a conversation with a friend telling me about his own family funerals. And at some point — probably not in a blinding flash, although that’s the way I remember — it occurred to me that that might be an interesting way to approach families.

If you kill four characters off in four funerals, you’re going to end up with a smaller cast at the end.

I like the sense that the book is narrowing down on what inevitably must be one remaining central character, and that in some tiny way, if you don’t know who that person is, it adds tension. The book is not building a narrative around characters in the usual way, which is to say that, in the terms that this narrative sets up, an arbitrary side character might occupy centre stage with as much significance as somebody who is more obviously, central to the project. This is a narrative that could have become untethered, and moved very far from the departure point. So in a certain sense, you have to keep returning to the central characters.

Galgut paid homage to EM Forster’s unfinished Arctic Summer

Galgut paid homage to EM Forster’s unfinished Arctic Summer

It’s actually a quality of epic, that you suddenly find yourself in the consciousness of a peripheral character, say the dog in War and Peace, or a different dog in Renoir’s film Rules of the Game. You’ve written a brief epic.

I like that term. I’m going to use that term now. I also like the fact that you picked up on the cinematic example of Rules of the Game, because I do think that the logic of focusing on a side image or a side figure of any sort, really belongs in cinema more than literature. And a lot of the rules of this particular game, the game of this book, come from film.

I heard you were making a film when you began writing this book.

I didn’t make the movie but I got offered the chance to write a couple of drafts of a film script. And it was a job I took because I needed money. I didn’t expect to get anything out of it aside from the money but, in fact, I got the narrative voice. I started off writing a third person novel when I was a callow youth and I haven’t really been back to that. My sensibility has been very locked in and it’s felt locked in. Because I suppose in some philosophical way, it seems to me that one can only live inside your own head and so it seems in some way untruthful to try to represent other consciousnesses because I know very little about them. Even when I did with a book like the Forster one, try a third person voice, it was still so tightly focused that it may as well have been in the first person.

I wonder if you have any thoughts about how this book is the fulfilment of things you’ve been working towards, or whether it seemed like an accident.

I’ve been frustrated with the limits of language imposed by first-person narration. If a student wanted to write a book in the way that I’d written this book, I would have said: ‘Absolutely not.’ It’s not how you do it, essentially. So I came up against that in myself. But I also came up against the instinctive sense that leaping from one perspective to another is far more in keeping with the way my own brain works, and that there is a freedom in letting that run. So I did it in an experimental sort of way, and the freedom was enjoyable, allowing me to do things in the book that were pleasing to me. So I went with it. But I was profoundly insecure right through the writing that this would convey to anybody else. I did show it to a couple of people along the way and asked them to be absolutely blunt in their assessment and tell me if it was a mess, and I was told it wasn’t.

I think our subconscious carefully screens the people we ask to be blunt. Let me ask about the title. Nietzsche says that the paradoxical nature of human beings is the creation of an animal that can keep its promises. I wondered if you had thoughts about South African history, the kinds of human beings we are, the promises we didn’t or couldn’t keep.

The Promise is also an overused title. It’s been used numerous times in numerous disciplines. It was the part of the book that arrived last. I had been working under a completely different title of Dark Love, which was an abstract allusion, too abstract I think, as it turned out, to Amor Swart. But I wanted to tie it in with a parallel sense that if one loves South Africa it has to be a dark kind of love.

In A Strange Room straddles memoir and fiction

In A Strange Room straddles memoir and fiction

I wrote a book a few years ago about Tolstoy, Gandhi, and Mandela, who were all concerned with the need for manual labour. They felt you had to work among the people, to drop your inner psychic barriers, get your hands dirty. In a country as corrupt as this one, it struck me that maybe that was also your solution.

I’m not of the school that believes novels should provide solutions. Very much not. I’m mistrustful of books that point the way to the future. I see us as recorders as of a particular moment, rather than agents of change. Why do you think the book is recommending manual labour?

I mean service to other people. What do your three siblings do? One marries a rich man and starts to hate doing anything with her hands. One wants to write a novel and gets only so far as writing fragments. And one, the sister Amor, finds herself working with HIV positive people in hospitals.

I wanted Amor to be the moral centre of the book, if the book has a moral centre. What if you want to give up the power and privilege? How do you do it? That doesn’t seem to be an easy way. So much has been said about white power and privilege, rightly so. But for those who would like to dispense with it, where do you go to return these items? I was drawing on aspects of my own nature for the creation of these various characters. There seems to be a recurring theme here in South Africa and not just in literature. That the way of honestly being South African is in some sense to be working class.

The Good Doctor is set in a desolate hospital in a former Bantustan

The Good Doctor is set in a desolate hospital in a former Bantustan

At one point Desiree says: ‘Why would you give a house to a maid? She’ll only break it.’ I thought that was a lovely example of humour being used for very cruel purposes.

I guess it’s South African humour. I have Anton remarking that South Africans are tone deaf to irony, but it seems we’re not the only ones. You know, it’s an old South African racist assumption that black people break everything, right. So it seemed like a funny notion that, you know, you might be able to break a house as well. If you don’t mention that certain characters are people of colour, and that other characters are white, but you introduce the kind of power dynamics that go with those relationships, you make it perplexing in a way for readers who don’t understand those reference points, and that sort of thing intrigues me — it’s like the edge of a literary map.