Ciao Bella Ms Cast: Venus Baartman, 2001. Courtesy of the artist and Dan Gunn, London

“I’m tired of seeing my face everywhere,” Tracey Rose laughed as she went about assisting the team at the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa at the V&A Waterfront in Cape Town setting up her retrospective exhibition, Shooting Down Babylon.

Covering Rose’s 30-year career, the exhibition is huge. Spread across 1600m² and three floors of the museum’s slick interior, the 300 works in various media — film, performance, painting, photography, sculpture and drawing — needed roughly four months to install.

With performance art as her predominant medium of choice — and her body always placed firmly at the centre — Rose has built a career consistently challenging, subverting and questioning everything from religion, racism and male dominance to colonialism and South Africa’s post-apartheid reality. There is little that escapes her irreverent, often satirical, always astute gaze.

Rose’s retrospective is, to some extent, vindication for the 47-year-old, whose provocative work and uncompromising ethos — her refusal to play what she calls “the good black” — had, for many years, resulted in her not “seeing [her] face everywhere”, especially not on South African soil. She says, with some disappointment in her voice, that her last show in South Africa was in 2011.

A few weeks after the opening of Shooting Down Babylon, Rose, currently a senior lecturer in fine arts at the University of the Witwatersrand, spoke about her near-suicidal days as an art world wild child, the softening effects of motherhood and her determination to use art as a tool for healing.

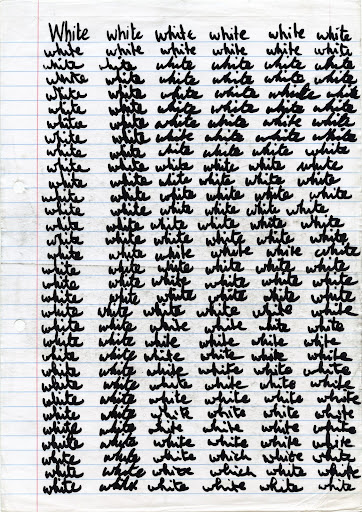

De Wit Man, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Dan Gunn, London

De Wit Man, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Dan Gunn, London

Looking at the work in this retrospective, I realised how much of your work I was not familiar with. Am I just out of the loop or are most South Africans not privy to this work?

Yeah, they’re not. I mean, I was blocked out of the art world. Nobody was exhibiting me here for the longest time. So I was just doing international shows.

Years ago, when we last had an in-depth conversation, you spoke of how disillusioned you were with the South African art world. Tell us more about that disillusionment. And do you feel that, with this retrospective at Zeitz, you’re stepping back into it? Do you feel a bit more at home now?

Yes, I do (laughs). It’s funny, Storm [van Rensburg, senior curator at Zeitz Mocaa] was interviewed [by] my students at Wits. And Storm says to my students — and he was the first person that actually articulated this — he said I’d been ostracised from the South African art scene. I mean, I always felt like I had been, but I always dismissed it as maybe paranoia. But when he said it, it was, like, ‘Oh, so it’s a fact. I wasn’t imagining this.’

You know, when Moshekwa [Langa] and I were, like, the two new black kids on the block …, they used to call him the wunderkind of South African art and I was the wild child (laughs). I mean, I was a bit crazy, but I was having multiple breakdowns, like, every two years. Like the post-exhibition depression [and] a bunch of other stuff. But the main reason was that I felt like I had to be “the good black”.

And really, I don’t want to be cooning. I’ve been playing coon face basically my entire career. I mean, it’s kind of what it was. It was like, ‘This is the gig, you’ve got to kind of pretend, otherwise the work is not going to be seen’, you know.

And at one point, I was really fucking snooty about where I’d show my work and who I’d show with. And then when the invitations stopped, especially when they stopped in South Africa, the only people that weren’t afraid of showing me were people internationally who thought that I made, you know, interesting work. And I started accepting residencies and invitations to places I would not normally have thought of or even considered before. And it wasn’t like the blue chip circuit. It was the B-side. A lot of them weren’t the prestigious spaces that I’ve been to before.

And it was incredibly humbling and incredibly fucking expanding. Because, if I’d continued on the art star trajectory, which I was supposed to have continued on, I would probably have killed myself. I would have ended my life before the age of 30. I was not happy about living on this plane. And I think I would have just been completely overindulgent. You know, been the superstar and then just died … I mean, every fucking day was a battle to wake up. It was like, ‘I don’t want to live. I don’t want to live. I’m gonna kill myself today.’

And then, just as I’m about to go and do it, I get an idea for a work. And it’s not even an idea. It’s a gift. It’s like, ‘Okay, you’ve gotta make this work.’ And then I’ve got to chase the work. I’ve got to make the work otherwise [it becomes] this monkey eating me up. And I had to make it by any means necessary. So, even if I didn’t have money, I would find a way. And in that process, I created my own visual language. Because I couldn’t do the super slick work I wanted to do, because I simply didn’t have the money. So I had to use detritus and scraps and kind of make it pretty. I was upscaling in my art before upscaling became a thing (laughs). And so an aesthetic — a visual language — kind of developed out of that.

I realised the other day that lockdown — that quiet time that Covid gave us; that meditative space where we all got klapped into dealing with our own shit (laughs) — kind of got me realising that, actually, I’m really shy. I don’t particularly like people. And I don’t want to actually do this. Like, art is too hard. I felt like it was a fucking expensive hobby, because I couldn’t survive off it. I’ve never survived off it. You know, my work is pretty fucking hardcore. And I wasn’t making, like, coon art that was gonna be pretty. You know, it’s not easy work to sell. So, I realised that, actually, Tracey Rose is a construct. Like, I had to invent a character in order to navigate the art world because it was so incredibly brutal.

The Kiss, 2001. Courtesy of the artist and Dan Gunn, London

The Kiss, 2001. Courtesy of the artist and Dan Gunn, London

What do you mean you had to construct a character to navigate the art world?

I mean, everybody kind of does that; sort of have different personas for different contexts. Then [artist, Zen] Marie said to me at one point, years ago, ‘Aren’t you afraid that you’ve become a caricature of yourself?’ And that was like an eina moment. Because I was like, ‘Fuck, actually he’s kind of right. When did I lose the plot?’

Did you ever think that you’d have your retrospective at the V&A of all places?

I’m glad it’s in Cape Town and not in Johannesburg. Because I don’t think there’s a space in Joburg that could actually have housed it on that level. And I really love what Koyo [Kouoh, executive director of Zeitz Mocaa] is doing … bringing really great, strong work and strong artists into the space to gain control in some way of the African art historical canon. To ensure that it is properly archived and cared for and nurtured.

I also love the manner in which the show was curated. Like, [the viewer goes] into these spaces, and [their] expectations are not met because … everything just gets disassembled. And that was it. Like, how do you essentially fuck [the viewer] up without hurting them? Like, how do you kind of pummel someone into a different kind of place — a different position — without the wounding and the trauma.

Years ago, you said to me, ‘Sometimes I just want to take a machine gun and do a 360.’ Basically, you felt everybody is fucked up. Do you remember that?

No, I don’t remember that. Was I drunk? (laughs)

Lucie’s Fur Version 1.1.1 – La Messie, 2003. Courtesy of the artist and Dan Gunn, London

Lucie’s Fur Version 1.1.1 – La Messie, 2003. Courtesy of the artist and Dan Gunn, London

I don’t know. We probably were, yes. Do you still feel the same way?

Fuck, no, I’m a mom. I can’t do jail time (laughs). I’m not interested in all those fuckers out there. There’s only one person that I’m interested in and that’s the one that came out of my pussy (laughs). I think it’s all still a process. Like, I haven’t solved anything by any stretch of the imagination. I don’t have some great philosophical answer or grand all-encompassing statement. It’s still a journey. It’s still work.

But I realised that, actually, the art is more important as a way to reflect society back to itself. It sounds like a cliche, but … My sensibilities changed. I don’t want to be as emotionally invested in the well-being of human beings. It’s too much work. There’s this notion that’s really messed up; that artists, who are generally always hungry and struggling and broke, are supposed to be the ones to somehow be the moral healers or something of society. But it’s like, no, you can’t expect that.

The conservative nature of art now is also another thing. It’s like woke culture went and eradicated a whole range of freedoms of expression. Like, Julius Malema was right: [The Russian state-controlled news channel] RT should be available [in South Africa]? He is absolutely right, because where does it stop? Because, if you stop RT [from airing in South Africa], you’re saying, ‘Now we’ve set the parameter for what is moral and what is right and this is the only voice that can be heard’. You know, I was watching RT on my phone and it’s hilarious. Because they’ve got like these little poppies that look like they are leftovers from Scope magazine, only they’ve got more clothes on. And they’re talking to these dudes that look like they’re leftover from the 1960s Soviet era — like dusty and crusty. And it’s fucking hilarious. You need to parody that shit. You need to ridicule it. But how can we do it if we don’t see it? How can we shoot it down if we’re not allowed to talk about it, you know?

I feel you. It’s as though cancel culture targets just about anything and anyone for the slightest infraction. What is the way forward, you think? What role can art and artists play?Art must just do what it’s always done — be the space for the freaks of society; the rejects of society. Like, sometimes my opinions get challenged by work I see, which is exactly what art’s supposed to do. For my MA paper … [part of what] I looked into was the origins of surveillance culture, which goes back to the Victorian era [when] basically people would spy on each other. That was part of the culture that was nurtured. And it is that kind of surveillance culture that I feel cancel culture is. It is very much part of that surveillance culture that seems incredibly Victorian in a sense. Even though what they are talking about, and what they’re trying to defend, are really progressive ideologies, their modes and their methods are, like, militant. And kind of fascist. It kind of doesn’t make any sense.

San Pedro V “The Hope I hope” The Wall, 2005. Courtesy of the artist and Dan Gunn, London

San Pedro V “The Hope I hope” The Wall, 2005. Courtesy of the artist and Dan Gunn, London

Earlier, you said “art is too hard” and an “expensive hobby”. Does that mean you are not planning on producing more work?

God, no! No, I’m making art. That’s what I do … You know, I’m seeing this more with a lot of my students, that a lot of them have callings and want to be healers. And that’s really the nature of what art is. Our people were dancing and singing in caves and painting on the walls way before there were institutions and structures that monetise that. And I’ve been [going through] the process of finding out what it is that compels me, every day, to make work. Because I have to make work every day, otherwise it fucks me up. And that’s a calling. That’s not a job. This is part of what my PhD is about. I’m trying to understand why I’m like this, you know. Because it’s not normal (laughs).

Maybe you need to go twasa. Maybe your ancestors are telling you …

That’s exactly what I should be doing, but I don’t know where to go. I mean, like where do coloured people go to twasa? We’ve got every fucking gene in our DNA. Like, what strand do you follow? And then you’ve also got the slave trader and the slave in your DNA. But really that’s what art is — and that’s what shamanism is — you’re healing through your craft. Because the people who have callings are actually on another fucking level. And that’s where the art is; the artistry is that calling. It’s not the fact that you have the ability to draw and paint.

Will you be doing another exhibition sometime?

Definitely. I mean, there’s always shows lined up and, you know, work that’s in process. This [retrospective] is just a reflection of what I’ve done in the last 30 years. And also, the importance of it being here. I want to use this post-exhibition period as a time for reflection and contemplation, drawing and painting. I need a hiatus from the extremity of performance art, for a more experimental period with its gentler relatives in the realms of theatre and film. I want to transition from my practice of the last 30 years to a less aggressive pace. Performance was a necessity because no one else was working in this manner. So I made a conscious decision that it was important to keep the door of this radical practice open to challenge and to expand the limitations of freedom of expression. But nowadays, everyone and their aunty is a performance artist.

Untitled, 2012. Courtesy the artist and Dan Gunn, London

Untitled, 2012. Courtesy the artist and Dan Gunn, London

If there is one thing you hope for your work to achieve, what would that be?

I often say that I am militant about art, but I am also militant about education. Arts education. Music, drama, fine arts, dance has to be taught in every school in our country — from grade R to matric. Those are our future patrons and practitioners … The arts contribute a few billion rands to the GDP and that’s without any governmental efforts. Imagine what that figure would be if they made an effort.

Anyway, what I want my work to do … it’s really all about opening the space up for further expansion in terms of, you know, critique and just conversation. Because the space for freedom of expression is incredibly precious to me. It’s like we’ve got to protect that. It’s so vital.

So I guess I would want to be remembered for saying, ‘Say what the fuck you want.’ Because as long as we’re talking, we’re not killing each other. And because what you have to say is fucking important.

Shooting Down Babylon is on show at the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa until 28 August