The talented novelist Nthikeng Mohlele’s debut short-story collection lacks the vitality that makes short stories magical

Award-winning novelist and, recently, short-story writer, Nthikeng Mohlele is among a new generation of diligent creative writers in South Africa. His 2014 novel Rusty Bell struck me as a lucid, racy and provocative piece of work. It tackled identity, race and class by invoking sensual themes in their historical South African political precarity.

Mohlele is at his finest when he delves into difficult existential realms such as the excesses of living in a fast-paced material world. As a storyteller, he is concerned about the fact that even good people can screw up, big time. Truly postmodernist but from the South African condition, Mohlele draws on voices, experiences and longings that belong to people who are not hankering after a lost golden past, nor those confined to the narrow and staid material and mental geographies.

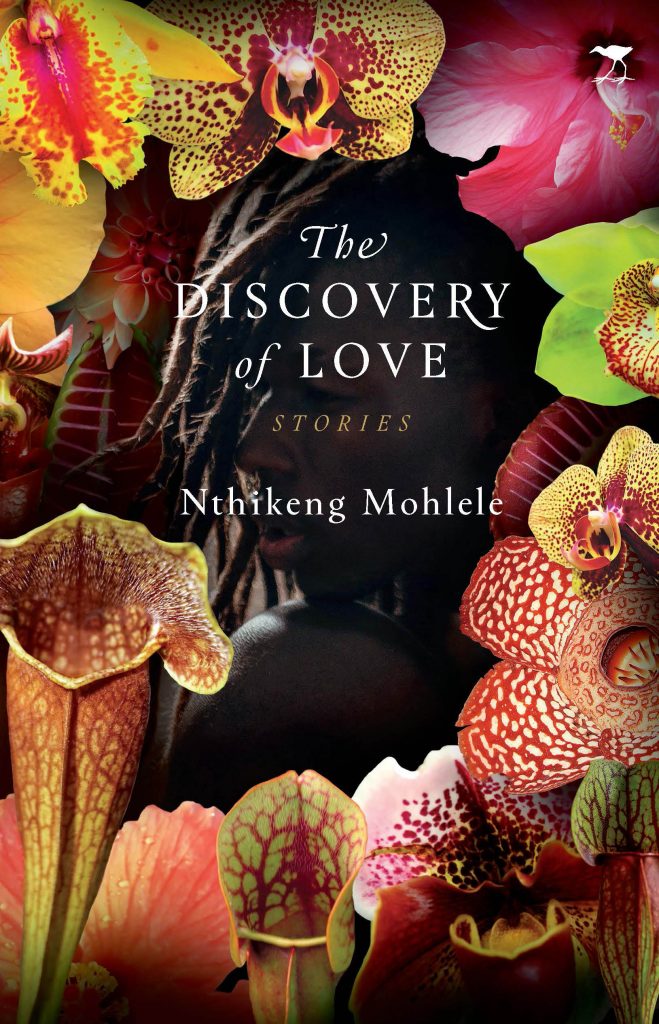

His debut short story collection, The Discovery of Love (published by Jacana Media), is strong. That is its charm. Love is presented through many lives — especially those for whom life is a bag of thorns.

The first story, Lessons in Love, is about a loving father who is raising his son after having separated from the mother. The story is an essay on adulthood and parenting from the perspective of a modern and open-minded black man. “You must understand that in raising a man, one has to raise oneself first: How do I know if a friend is worth keeping? What is the real purpose of a girl having a period? Which is more important, money or peace?” The love lesson is straightforward, tender and warm to the narrator’s son.

The narrator is excited when his teenage son, a promising music composer, falls in love. Melody is “very pretty in fact, with smoky brown eyes, a dimple and kissable mouth”. Although the narrator’s male voice comes out clearly in the story, offering a well-rounded, delicate yet balanced view of his world, without dialogue, its latent fire dies rather quickly. Instead of the other characters speaking, laughing, dancing and fighting, the reader is stuck with the monotonous voice of the omniscient narrator, who ends up sounding like an old geezer. For instance, when he offers advice to his love-struck boy, the narrator comes out as a cool cat. “So, whenever I can, gently offer advice: refrain from the affections of other girls while enjoined with Melody, hold no grudges, praise and cajole, hold hands whenever so requested …” Having the young lovers going through these real-life experiences would have breathed life to the story, which ends abruptly.

Mohlele also tackles the bigger political themes such as racism. He alludes to the murder of George Floyd, a 46-year-old black man killed by a white police officer in the US in 2020. “There are other searching and often bewildering questions: If white people oppressed black people for over four hundred years, how come black people are so nice to them, including in America where police seem to kill them for sport? A policeman kneed a grown man to death, ignored his pained pleading until he took his last breath — how can humans be that heartless?”

On the other hand, The Grape Picker reads like a long letter from a distant lover. In the cleverly conceived but poorly realised story, the letter never arrives. The story is a cutting meditation on working-class people’s living conditions and rights, the wrenching effects of poverty, powerlessness and capitalist exploitation in the Western Cape winelands. “We, on the farm, waited with bated breath for our lives to get better … They remained the same, only with newer afflictions consistent with growing up, with the monotonous life of picking grapes. There are particular kinds of suffering that cannot be explained, except that they prolong a misery that is premised on lack, on powerlessness, on striving to live and do better amid damaged hope.” The speaker is a wine farm worker, besotted with a fellow worker. “Anna-Marie Michaels, beautiful lady with a ready blush and reserved personality, whose smile could part clouds and rid the vineyard of all manner of impurities.”

Picturesque and brutal in its evocation of place and pain, The Grape Picker, though better in exposition, also lacks movement that drives action behind the author’s expansive sweep and philosophical ambitions. Only the narrator speaks, and at no stage do we hear the voice of Anna-Marie Michaels, the woman he desires and thinks about.

In I Am a Woman a dazzling woman narrator, fed up with romantic liaisons with men in favour of a solitary life, declares: “You have to understand that I love men, adore them and cannot consider my life — its history and contortions, its tensions and triumphs — without linking it to men.” For leisure, the narrator now plays classical piano, and has “raided second-hand bookstores in Houghton and Melville, mostly poetry, and some existential and other philosophers: Camus, Sartre, Homer.” The story has great suspense. But again, because so much happens in the mind of the narrator, little moves. A cold-blooded murder of a lover only ends the musings of a bruised, lonely mourner.

At the end, Mohlele, who may be gesturing towards Anton Chekov, Virginia Woolf and Katherine Mansfield, who defy narrow technical demands of narrative form and setting, could have done better in creating more rounded settings for his work. Sadly, Mohlele only succeeds in offering a series of tantalising lectures on love and the black condition, but fails to deliver on compelling narratives.