Mbuzeni Zulu poses for photos after an event to

honour him in June. (Oupa Nkosi)

‘One day, when I was coming out of the darkroom, I saw Yvonne [Chaka Chaka] and I greeted her and she greeted me back. She then went straight to the darkroom … I knew something was not right. I followed and, when I entered, Yvonne was screaming at Mbuzeni [Zulu] accusing him of gossiping about her to Brenda [Fassie],” former photo editor Robert Magwaza tells the crowd — which bursts into laughter.

Magwaza was sharing fond anecdotes with a group of friends and former colleagues gathered to honour and celebrate the life and legacy of the retired photojournalist Mbuzeni Zulu at Wandies Place in Dube, Soweto. The event was held on 18 June, a week after the burial of yet another unsung hero of photojournalism, Mike Mzileni.

A sad norm in this country is that many accomplished people are only celebrated when they are dead, however, Zulu is one of the lensmen who has been bestowed with such an honour while still alive.

Laughter was in abundance as speaker after speaker showered the 69-year-old with praise about his pivotal role in the photographic world and his 26 years of service at the Sowetan newspaper.

Singer Brenda Fassie and Yvonne Chaka Chaka on the way to Fassie’s wedding. (Mbuzeni Zulu)

Singer Brenda Fassie and Yvonne Chaka Chaka on the way to Fassie’s wedding. (Mbuzeni Zulu)

Despite their quarrels in the past, the Princess of Africa graced the event to show support to the cameraman. Dubbed the original paparazzo — he gave showbiz people like her exposure before the fame and money — Zulu became the unofficial personal photographer of Chaka Chaka and the late Fassie.

Guest speaker, veteran journalist and activist Joe Thloloe, thanked Zulu for “making our lives richer” with the work he had produced over the decades.

The invariably courteous and soft-spoken newsman described Zulu as self-effacing, tenacious and a hard-working photographer who was often at the right place at the right time for the clink.

“The range of the photographs that you took is vast. You covered children’s birthday parties and celebrities getting married. You still remember Brenda,” said Thloloe, referring to the love-hate relationship, which ended with Zulu suing Fassie for breaking his camera at an event in Durban.

He also told an amusing story explaining to the guests how Zulu got the nickname “Goat”, by which he was affectionately known in the newsroom. Apparently, his late friend and mentor Moffat Zungu abbreviated Mbuzeni to Mbuzi — imbuzi means goat in isiZulu.

Zulu was delighted when Magwaza presented him with an A1-size collage, printed on canvas, of some of his work taken from negatives he thought he had lost long ago.

Musician Ray Phiri. (Mbuzeni Zulu)

Musician Ray Phiri. (Mbuzeni Zulu)

What makes Zulu tick?

Born into a large family of 11 siblings, he attributes his many talents to his parents, who were both prophets and who ran a successful church.

Before he accidentally got into photography in 1978, he was a painter and sculptor.

“The first time I held the Yashica camera, that my late brother Bonkosi gave me, I went into photography wholeheartedly,” he tells me.

While fiddling with the camera at home in Senaoane, Soweto, he began taking snapshots of people, of birthday parties, weddings and music events.

“I went everywhere carrying a camera and I would take pictures of everything,” Zulu says.

His eclectic taste in photography opened doors for his work to be published in various publications such as Golden City Press, Drum and Staf frider.

At Sowetan, he was initially paid R5 per photograph used, which drove him to work harder. In 1982, he was hired full time and remained at the newspaper until 2008.

The enigmatic documentarian does not talk much and is unassuming. During his illustrious career he preferred using public transport when chasing stories. This odd way of working was influenced by his political activism during apartheid, when he need to evade the police and prevent the government from knowing his whereabouts.

Author, curator and filmmaker Bongani Madondo, who is author of Sigh the Beloved Country and editor of the book I’m Not Your Weekend Special: Portraits on the Art, Life + Style & Politics of Brenda Fassie, has paid critical attention to Zulu’s work for years and has used some of his images in his projects.

Madondo refers to him as the “visual stenographer” of the burgeoning black township-based popular culture that came out of the Black Consciousness Movement in the 1970s and bloomed in the 1980s and early 1990s.

“He is the closest equivalent to a photographic biographer of Brenda Fassie. Not only of Brenda, but of the scene that included Yvonne Chaka Chaka, Dalom Kids and Sello ‘Chicco’ Twala — basically the breadth and depth and the width of black township popular culture,” he says.

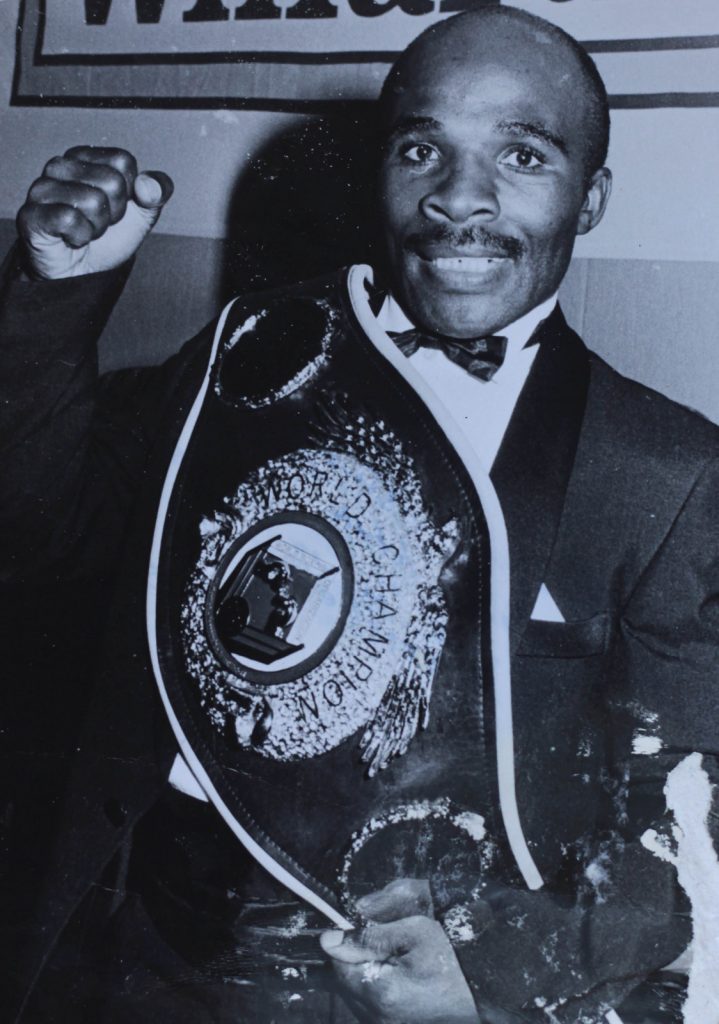

Boxer ‘Baby Jake’ Matlala. (Mbuzeni Zulu)

Boxer ‘Baby Jake’ Matlala. (Mbuzeni Zulu)

At the peak of the unrest before South Africa made the transition to democracy, Zulu was accused of being attracted to violence and bloodshed.

He tells of the time at Kwesine Hostel, in Katlehong, when Inkatha Freedom Party supporters, carrying all kinds of dangerous weapons, approached the vehicle he and his colleague Joe Ndlela were in. Ndlela fled, leaving Zulu behind.

He was brutally attacked and abducted and all he remembers was “waking up at the Sowetan offices” and being told that the Army Peace Force had rescued him from the angry mob. Ndlela eventually left the profession to become a pastor.

On 13 January 1991, Zulu was assigned to cover a soccer match between Kaizer Chiefs and Orlando Pirates at Oppenheimer Stadium in Orkney, in North West. It was expected to be a fiercely contested and entertaining game, however ,the day ended with 42 supporters dead.

In his speech at Wandie’s, Thloloe confessed he had once accused Zulu of “being addicted to blood and death” and having said he “seemed to smell it and follow the scent”.

Zulu would cover contentious stories by himself and provide the newsroom with information and film to be processed. There are rumours he was once moved to cover less heavy stories but he got upset and demanded to be brought back to cover what he was accustomed to covering.

A cow reacts after being

taken by comrades from a funeral in Soweto. (Mbuzeni Zulu)

A cow reacts after being

taken by comrades from a funeral in Soweto. (Mbuzeni Zulu)

Copyright issues

Last year, American streaming service and production company Netflix teamed up with Sowetan to celebrate its 40th anniversary by recreating archival images relating to the entertainment industry.

Two of Zulu’s images were redone — a portrait titled Wedding of the Century of Fassie and her maid of honour Chaka Chaka in a limousine and one of dancer Thembi Nyandeni performing with the band Amampondo. Sadly, he was not given credit for either of the photographs in the initial social media releases and video clips.

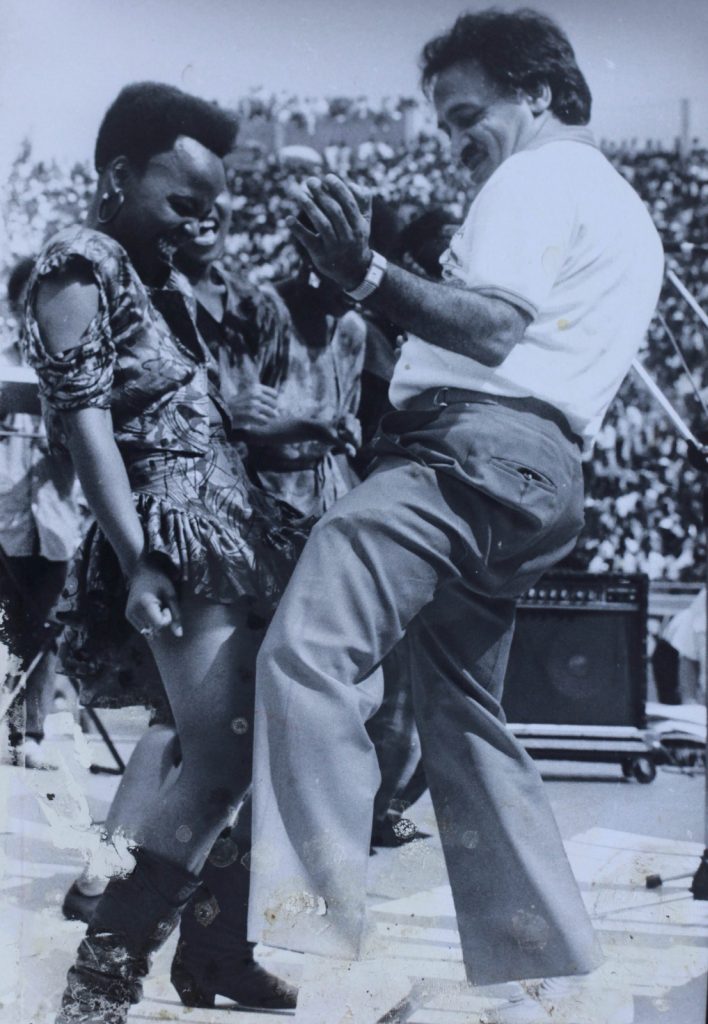

Abdul Bhamjee dances with singer Rebecca Malope. (Mbuzeni Zulu)

Abdul Bhamjee dances with singer Rebecca Malope. (Mbuzeni Zulu)In a piece Madondo wrote for the Daily Maverick on this issue, he credits veteran Cape Town-based international photographer Fanie Jason for highlighting on social media such gross misconduct by major companies, cheating artists of intellectual property rights, payments and exposure.

Subsequently, Sowetan, which reserves copyright although there were no clear lines when photographers were hired at the time, corrected the omission. However, none of the photographers whose images were used were compensated financially.

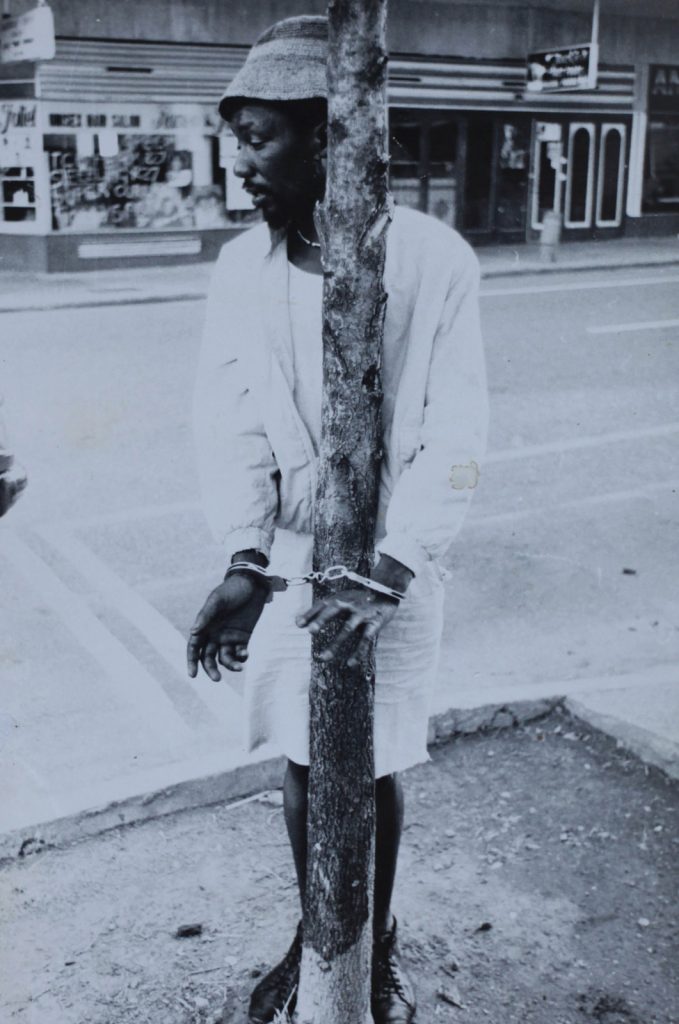

A man arrested for scavenging in rubbish bins

A man arrested for scavenging in rubbish binsRetirement and future plans

Zulu is living a quiet life in Senaoane. He’s been exploring his artistic side, decorating walls with mosaic tiles and creating small sculptures. He is also involved in community work and is a member of a church choir.

He plans to write a book about his life, exhibit his extensive portfolio of work and run photographic workshops for disadvantaged children.

Basetsana Makgalemele wins Miss SA in 1994. (Mbuzeni Zulu)

Basetsana Makgalemele wins Miss SA in 1994. (Mbuzeni Zulu)