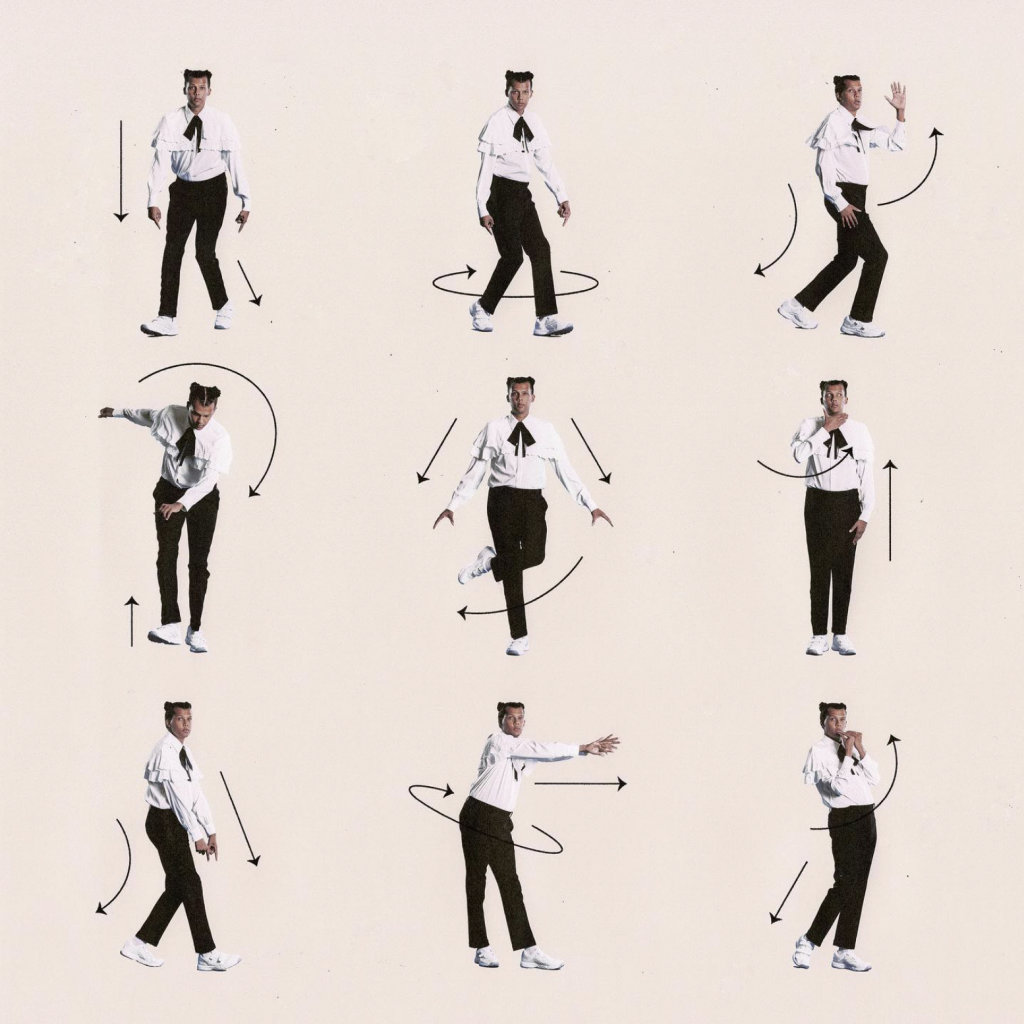

Stromae in his half femme half masculine look for the Tous Les Memes video, still by Mosaert

Oftentimes, pain and testimony are appointed as the beacons for meaningful art, art with depth, and art with lessons to teach us. Pain and testimony are also powerful pieces of currency in the art world, which has arguably always been dominated by white fetishised and sensationalist interests.

As a result, there is an over-representation, and over-manufacturing, of pain and testimony, and subsequently, singularity.

In Stromae’s latest album, Multitude is both the beacon and the title.

Belgian and Rwandan musician Stromae released his third full-length album this year after a nine-year hiatus. Stromae’s break from producing music, performing and touring was somewhat informed by what he has stated as a lack of balance – all work and no play; singularity when it came to producing work.

The cover for Stromae’s album Multitude renders many versions of himself

The cover for Stromae’s album Multitude renders many versions of himselfMultitude then arrives feeling, reading and sounding like an evolution.

The 12-track album is largely about the process, Stromae’s process. While testimony is Stromae’s departure point for the themes of the album, there is a use of imagination that transforms a song or a lyric into a larger world that invites the listener to see themselves in.

Multitude stages conversations in intimacy and the everyday. The tracks discuss depression, solitude and the pressure of isolation (La Solassitude), autopilot-like romantic relationships and their hollowness (Pas Vraiment) and mundane tasks such as Stromae changing his baby boy’s nappy (C’est Que Du Bonheur).

While these moments or experiences are generally thought of as things to get on the other side of, Stromae takes the time to blow them up in size, often with a dance beat behind them – showing the everyday realities (and difficulties) that make a life, as opposed to only the major moments.

As a member of pop music’s avant-garde, Stromae’s signature is pairing intense lyrics with upbeat music and a distinctive dress sense. This effect is exemplified in Papaoutai, perhaps one of his most recognisable songs. The fast-paced electronic dance song’s lyrics plead:

“everyone knows how to make babies,

but no one knows how to make dads …

Where are you?

Papa, where are you?”

This kind of pairing of heavy topics with dance music has clear wit and intentionality that goes beyond a categorisation of juxtaposition. Rather, there is a demonstration of how difficult moments live with bright ones. These kinds of compositions speak to the very human desire to dance, to have a drink (or many), to indulge or to escape following a painful, harmful or exhausting experience.

Visuals for Multitude’s first single, Santé

Visuals for Multitude’s first single, SantéMusically, Multitude is an album that has a kind of familiarity to it. Like past albums, there is a club quality and overall immensity to the tracks. Multitude’s soundscape retains the immensity while sounding like it is from all over the world. Throughout the album, there is instrumentation that includes erhu, a traditional instrument from China, Congolese drum patterns, Japanese-inspired instrumentation and Brazilian Baile funk. There is also song structuring that is reminiscent of brassy and bouncy folk and children’s songs, as well as the incorporation of harpsichord, big brass melodies and Spanish-like guitar stylings.

What connects these disparate and varied sounds is familiarity. Stromae takes sounds we might have heard in passing – while travelling, in a film or on the radio – and gathers them up into Multitude’s world. Even if they don’t know exactly how Brazilian Baile funk sounds, it still sends the listener the signal that this is a song to move to.

In this way, the album pulses with the kind of intuition that Dionne Brand writes about in The Blue Clerk: “It was December, we had brought a bottle of rum, some ancient ritual we remembered from nowhere and no one.” The many sounds that make up Multitude feel like tapping into an intuitive sense of knowing that is relied on especially for people descended from enslavement or living in diasporas. In doing this, they feel as if they allow for connections across histories and oceans – even those that have been broken by time and power.

Multitude is compelling in the way it unfolds. The album becomes more and more complete as an artistic piece with accompanying music videos, the distinct clothing and visual styles and characters, and the presentation of these in live performances.

Stromae in his Fils De Joie music video, photo by Lydia Bonhomme

Stromae in his Fils De Joie music video, photo by Lydia Bonhomme

Stromae’s styling is incredibly playful and has been long-time supported by the creative label Mosaert. From an Ariana Grande-style ponytail to the white blouse and braided bun combination that accompanied the album’s first single, Santé, these stylings not only establish a character but also breathe refreshing breath into the performance of masculinity, something to which Stromae is not new. In the visuals for his previous album, he dances playfully with gender. Tous les Mêmes (All the Same) features one side of Stromae’s face and body painted as femme and the other as masculine. The overall experience of Stromae’s style is fun, simply because it is not spectacle, but part of his world-building.

L’enfer (Hell), the album’s standout second single, discusses suicide ideation. On its own, the song is bombastic with looped vocals that emulate chanting or screaming. The music video adds another layer by bringing in Stromae’s vulnerability.

The chorus of L’enfer reads:

“I’ve considered suicide a few times

And I’m not proud of it

Sometimes you feel it’d be the only way to silence them

All thesе thoughts putting me through hell

All thesе thoughts putting me through hell.”

The video cycles through him singing the song and experiencing exhaustion, anxiety, anger and being unable to cope. Stromae also puts his candour on display in the way he performs the song live. His Coachella performance this year used eight robotic arms with screens to create stunning dynamic visuals to capture the volume of the song’s essence and experience.

In another setting, he performed the song on a news segment, almost as a surprise. After about two minutes of discussion about the new album, the newscaster sets Stromae up by asking him if music helped him deal with the loneliness he discusses so freely on the album, and instead of answering her, he starts with L’enfer. And without any camera play or live musical backing or change in the newscasting background, Stromae sings about his vulnerability and achieves this through sincere performance.

Another standout on the album is the music video for Fils de Joie, meaning son of a hero or son of joy. The song’s lyrics establish a narrator who is defending their mother, and seemingly the work their mother does, and the critique that has been thrown her way for the way she provides. The video opens with a black screen with two lines of text, one in English, one in French, that set the stage for the video:

Dans un pays imgainaire, l’état organise les funérailles d’une travailleuse du sexe défunte

In a fictional country, the state holds a funeral for a missing sex worker.

It then launches into a large state funeral in an outdoor plaza, with an audience of what looks like more than 1 000 people. Stromae is at the podium giving the national address, singing about his mother as processions take place:

“But hey!

Leave my mother alone

Yes I know, she’s not perfect, it’s true

She’s a hero

And I will always speak of her with pride

I’ll speak of her with pride.”

The video is massive in scale and style, and it too has a multitude of influences informing this imaginary state. Stromae’s functional country recreates national symbols, processions and military plane formations, and repurposes these traditional tools of power and state mythology into communion for a world that mourns the loss of sex workers, for a world that seemingly practices an ethic of care. In the marches, dances and processions, we see a multitude of racial identities and cultural practices, from river dancing to a funeral procession of dancing and dancers inspired by traditions around death in Ghana.

The world and multitude of Stromae feels and sounds like communion. It shows his ability to work across multiple genres, multiple lyrical themes and tell visual stories that are specific but able to become their own world. Multitude’s beacon provides a guide through banality, through excitement, through deep pain and through the dance we do at the end of it all.