In colour: Cheri Samba’s Une Femme Conduisant le Monde is part of the exhibition titled When We See Us: A Century of Black Figuration in Painting, which opens at the Zeitz Mocaa in Cape Town later this month.

In one of her most well-known poems, Poem About My Rights, June Jordan writes, “I am very familiar with the problems of the C.I.A. / and the problems of South Africa and the problems / of Exxon Corporation and the problems of white / America in general and the problems of the teachers / and the preachers and the F.B.I. and the social / workers and my particular Mom and Dad / I am very / familiar with the problems because the problems / turn out to be / Me … I am not wrong: Wrong is not my name / My name is my own my own my own.”

While colonialism, enslavement, and the anti-black nature of the world are highly visible and tangible, their impact on the place of imagination — who is imagined as wrong — is profound. As much as physical and structural violence is, and was, a part of the colonial project, discourse, images, media, fashion and imagination are just as pertinent sites of domination.

When We See Us: A Century of Black Figuration in Painting, the Zeitz Mocaa exhibition opening at the end of the month, stages conversations between black and African artists, continental and diasporic, that do not concern themselves with being wrong. Rather, this large-scale and robust exhibition of more than 200 artists invites debates, tensions, overlaps and non-overlaps between black figuration, art that is visually representative of the human form, over the past 100 years. The exhibition comes through a partnership between Gucci and the Institute for Humanities in Africa at the University of Cape Town via a 14-part webinar series.

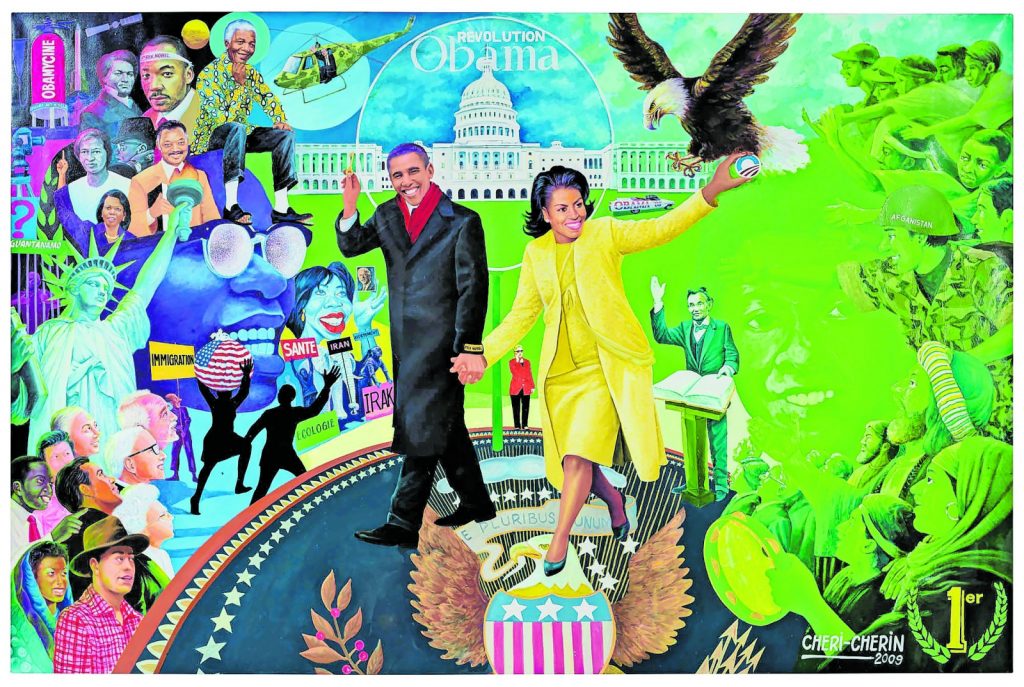

Revolution Obama is also a part of the exhibition titled When We See Us: A Century of Black Figuration in Painting.

Revolution Obama is also a part of the exhibition titled When We See Us: A Century of Black Figuration in Painting.

The exhibition takes its name from Ava DuVernay’s Netflix series When They See Us, which retold the story of five innocent black teenagers who were coerced by New York police into confessing to the rape and murder of white woman jogger in 1989. They spent between six and seven years in jail and the oldest spent 13 years in an adult prison. The series is emotionally demanding but does not depict a unique set of circumstances, even in its incredible violence.

The history of the criminal justice system in the US is a transformation of slavery, where scholars Zoé Samudzi and William C Anderson note the markers of enslavement were transformed into the markers of incarceration. While the realities depicted in the series are egregious, it is also a recurring consequence of a system that works to trap, monitor and target black people.

What stands out about the series is the reasoning behind the title. When They See Us casts a line out into the future. It suggests there is already an affirmed vision of unconditional human dignity for black people, particularly, these five black men. For those who can’t already see, the depiction allows one to arrive.

When We See Us as an exhibition and an ongoing project honours and interprets this notion into the place of art and owning our narratives.

Koyo Kouoh, executive director and chief curator of the Zeitz and of When We See Us, emphasised the importance of having the show now: “This exhibition challenges centuries of cultural erasure and historical omissions. Accompanying the exhibition is a timeline that traces how literature, festivals, political events and other key moments have contributed to the ways in which we see ourselves today.

Shadows: Congolese artist Moké’s Kin Oyé

Shadows: Congolese artist Moké’s Kin Oyé

“Of course, it is not an exhaustive timeline. However, we included it in the exhibition to offer more context to guide audiences to better understand how other art forms and key events contribute to the critical discourse on topics such as pan-Africanism, the civil rights movement, African liberation and independence movements, the anti-apartheid and black consciousness, mobilisations, decoloniality, Black Lives Matter and beyond.”

When We See Us arrives with anticipation as recent shows like Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963–1983, first conceptualised and exhibited at the Tate Modern in London, or ongoing shows such as Yakhal’ Inkomo at the Javett Art Centre in Pretoria have been well received in their curation of black art that exists within landscapes of politics, music and representation. These exhibitions, which focus on highly politicised times and the work black and African artists made, demonstrate a necessary aspect of world-building; where a world is reconstructed for viewers to look on, see oneself and one’s context, and walk among the varying ideas and fashions and representations of a specific period often overdetermined by a narrative of pain and struggle only.

This same world-building that is vivid and visually driven is evident in When We See Us. As Kouoh notes, “It shows not only the wealth of artistic production in this field over the past century, but also invokes the simultaneity of practice and parallelism of forms that run through time and through generations of artists.”

There is an excitement in all the texture that the exhibition brings together. And what is revealed through the work is wonder, fascination, honour, imaginativeness and a reaching out that is done when black artists depict themselves.

Zandile Tshabalala’s Two Reclining Women

Zandile Tshabalala’s Two Reclining Women

For example, there is playfulness and a care for everydayness in how our public spheres are portrayed. Kin Oyé by Congolese artist Moké is an oil-on-canvas piece that depicts a sultry nightclub scene, illuminated by colourful lights, creating shadows in deep hues. Antoine Obin’s Untitled portrays schoolgirls in uniform, their hair accessorised with hair clips and bows, books by their sides.

Intimacy is on display as well. Never Change Lovers in the Middle of the Night by American multidisciplinary artist Mickalene Thomas is a scene of two black femme lovers tangled in bed, faces hidden, against bright yellow and blue walls on red bedding. The mixed-media piece is dazzling as one looks close to see parts of the lovers’ rich skin, afros, feet, bedding and clothing are composed of rhinestones.

Teju by Amoako Boafo

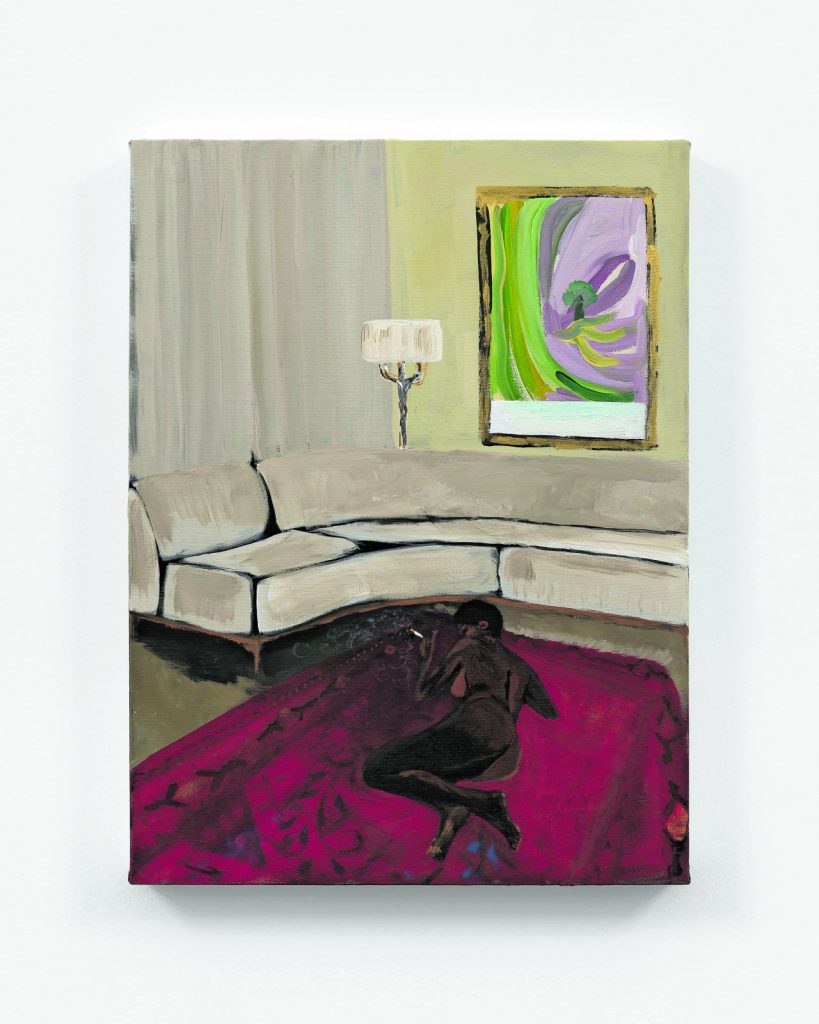

Teju by Amoako BoafoDanielle Mckinney’s OCD and O’keefe depicts a black woman, naked, short hair, lying on her side, back and head to the viewer. She lies on a red carpet in an upscale living room with a white couch against a wall with art on it. In the woman’s hand is lit a cigarette. The brush strokes and the use of acrylic paint bring immense depth to such a private moment.

Similarly in depth, Teju by Ghanian artist Amoako Boafo is a waist-up, up-close portrait of a black woman that details the brush strokes of browns, blacks, blues and reds of the subject’s face, hair and hands. Teju presents a figure whose face, hair and hands are fluid, complete but ongoing.

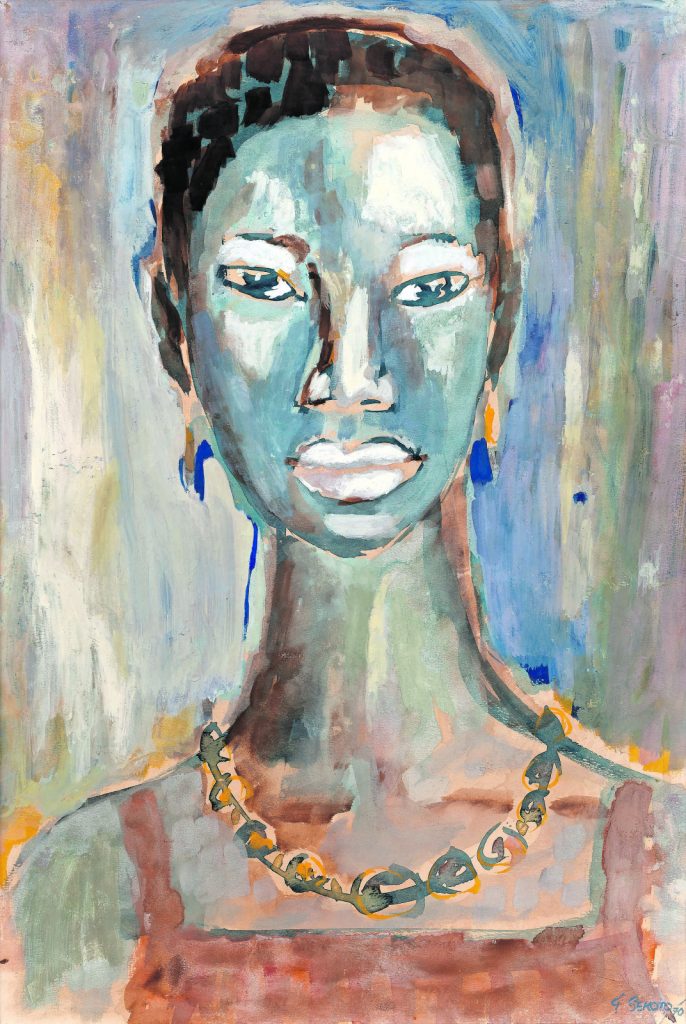

When it comes to South African art, there are contemporary and canonical works on display with Zandile Tshabalala, Sphephelo Mnguni and Gerard Sekoto. The inclusion of an artist like Sekoto calls in the South African canon, with Sekoto’s surrealist work being foundational and influential for black South African visual artists. His Portrait of a Woman is one example of his stylistically dynamic portraiture of black people, where the texture of hair and the essence of a face is identifiably black through a medium-blue hue used for most of the woman’s features. There is an intersection of otherworldliness and grounded beauty and essence.

Intimate: Danielle Mckinney’s brush strokes and use of acrylic paint bring immense depth to her work as seen here in OCD and O’keefe.

Intimate: Danielle Mckinney’s brush strokes and use of acrylic paint bring immense depth to her work as seen here in OCD and O’keefe.

In the variety of self-representation lies a mapping of the evolutions of style, fashion and adornment. There is an affirmative love in aesthetics of the depicted black people, particularly dark-skinned black and African women, across these works; an affirmative love for ways we black people style ourselves, from hair to clothes to the confidence and comfort in the body.

Scholars Julia Watson and Sidonie Smith, who have written on the practice of decolonisation and the role of autobiographical writing, emphasise “the colonial subject inhabits a politicised rather than a privatised space of narrative”. In other words, there is a denial of self-representation due to an overly politicised identity. Watson and Smith offer that autobiographical writing, namely for black and African women, can be a part of the decolonial project shifting from spectator to actor by utilising knowledge systems, cultural practices and what we know to be true to create and re-create realities and desires that are not fenced in by the punishments of politics.

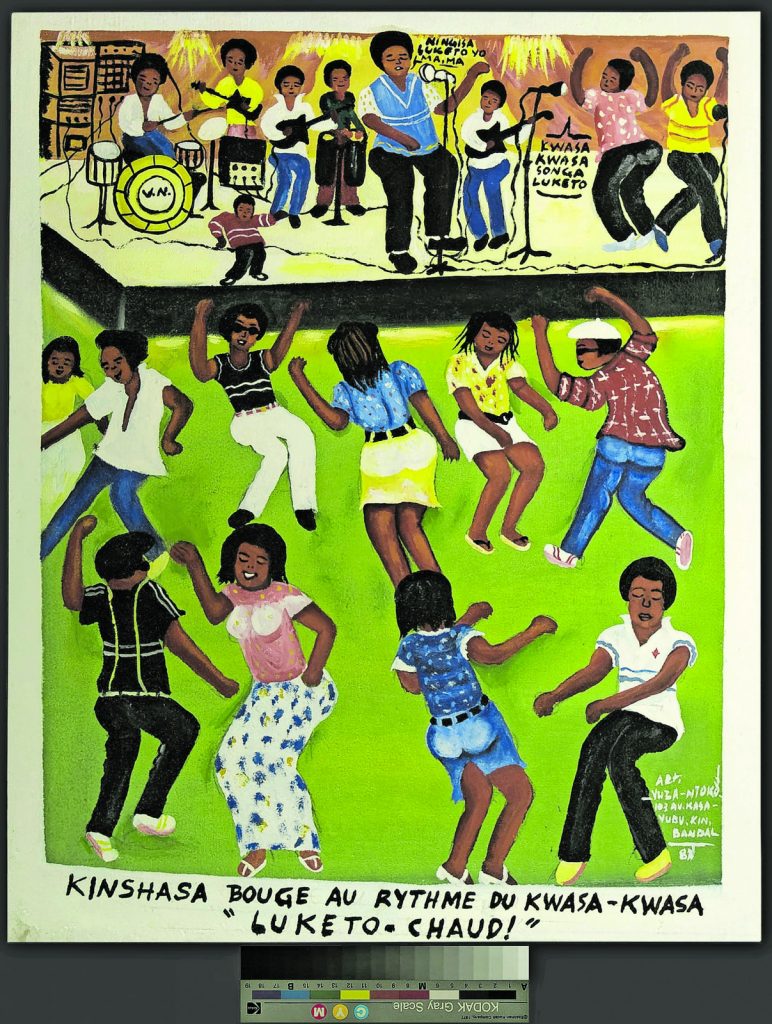

Vuza Ntoko’s Kinshasa Bouge au Rythme du Kwasa-Kwasa Luke to Chaud!

Vuza Ntoko’s Kinshasa Bouge au Rythme du Kwasa-Kwasa Luke to Chaud!

The representation of self rejects how fashion and aesthetics have been used against black and African people. Everything from hoodies in the US to the pencil test in South Africa, the degradation of blackness, of the black body, attracts violence and in many ways makes violence permissible. Figuration and visual archives remain a critical means of existing and of making worlds that are sometimes more tenable than this one.

Importantly, the work of self-representation cannot be characterised in static and inflexible ways. The serious work of building archives, vocabularies and imagery demands a commitment to being un-fixed; the canon and the work do not have clear lines or finish lines. It is ongoing and in conversation with what comes next and what becomes less opaque over time.

Gerard Sekoto’s Portrait of a Woman

Gerard Sekoto’s Portrait of a WomanKouoh emphasised the importance of self representation and the exhibition of it and how this puts on display the plurality of black creation. “This exhibition demonstrates how black subjectivity can manifest through joy. Joy can manifest in the form of play, idleness, leisure, indulgence, opulence, spirituality, belonging, communing, triumph and sensuality.”

When We See Us offers doors into histories, legacies and debates across black and African geographics, aesthetics, sonics and cultures and demonstrates writing oneself in, painting oneself in, and sculpting oneself is affirmatively saying, “We see us.”

When We See Us opens on 20 November at the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town and will be on until 3 September. For more information and tickets, visit https://zeitzmocaa.museum./