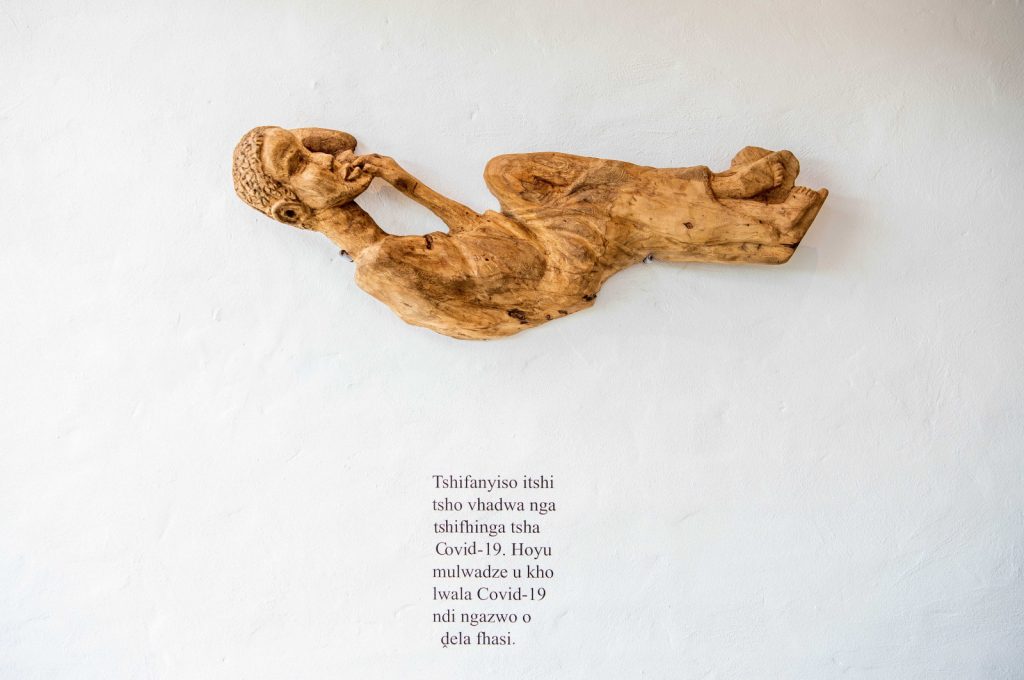

Work from Noria Mabasa's exhibition Shaping Dreams at the Nirox Sculpture Park. (Supplied by Lucky Lekalakala)

During her two-week residency at the Nirox Sculpture Park in Krugersdorp, northwest of Johannesburg, in May, world-renowned sculptor Noria Mabasa said in her 40-year career, she had never attempted to create a piece without obtaining blessings from her ancestors.

“Whenever I don’t receive visions, my head aches,” says the 84-year-old recipient of the 2002 Silver category of the Order of the Baobab for exceptional service to the country.

Born in 1938 in Shigalo in Giyani, Limpopo, into patriarchal Venda culture where only men worked in wood, she became the first woman to break that gender stereotype.

Her work deals with traditional issues, particularly those pertaining to women, as well as mythology and spirituality. It depicts the harsh realities of life in rural areas and work towards social transformation.

Mabasa is a custodian of indigenous knowledge and is a respected teacher who willingly shares her knowledge and skills. She found recognition on both the local and international art scenes in the 1980s and has won numerous awards for her outstanding artistry and creativity.

Dressed in a white dress and T-shirt, a few long, grey dreadlocks escape her pink doek. She gestures fluidly when telling the captivating story of her creative process.

She says she takes a nap to ease her headache and, as soon as she receives a vision, she wakes suddenly, excited to begin working on a piece of wood.

One of Mabasa’s pieces, depicting “a white man that threw someone in the lion’s den”, was carved from a large piece of discarded wood she found at a field in Ga Manamela in Limpopo. She was referring to the case of Hoedspruit farmer Mark Scott-Crossley who was sentenced to life in prison for killing one of his workers Nelson Chisale in 2004 by throwing him into a lion enclosure.

Channelling ancestors: Noria Mabasa. (Yusuf Essop)

Channelling ancestors: Noria Mabasa. (Yusuf Essop)‘Shaping Dreams’ and curatorial processes

During Mabasa’s residency in May, which coincided with Africa Month, she intended to celebrate her legacy and heritage by creating a new body of work, including that for her exhibition Shaping Dreams which was in two parts. She conducted workshops with local universities and schools about wood carving and talked about her work during the exhibition of 38 works, made from wood and clay, in the residency studio.

“She moves quickly at 84 years old; it is quite amazing to see,” says 32-year-old Sven Christian, who curated both exhibitions — the first was held in May and June at the residency studio and the second runs until 20 November.

Christian was familiar with Mabasa’s work from catalogues and exhibitions but was surprised at the unconventional way she works.

“It’s very rare to see how someone makes her work. You get to learn with a degree of separation,” he says after the official opening, while guests indulged in food and drink in the 15-hectare landscaped park in the Cradle of Humankind.

There are two particular experiences with Mabasa he cherishes. One was when he visited Mabasa’s home and studio at Vhutshilo Arts and Crafts Centre in Tshino, Limpopo, to select works for the exhibition.

“It came time to gather details related to each work — title, medium, dimensions and so on. When pressed for titles of her work, however, Mam Noria often opted for the anecdotal, preferring to tell lengthy stories about each work,” he says.

Another was in May when he asked her to talk about her work during the first part of the exhibition and her response was, “But it’s not me,” implying she does not view herself as the author of her work, but rather as a conduit for the ancestors. This is a direct challenge to the idea of authorship and the prevailing celebration of artistic genius.

Work from Noria Mabasa’s exhibition Shaping Dreams at the Nirox Sculpture Park. (Supplied by Lucky Lekalakala)

Work from Noria Mabasa’s exhibition Shaping Dreams at the Nirox Sculpture Park. (Supplied by Lucky Lekalakala)

Christian had to think outside the box to condense the anecdotes into titles which would fit the conventions of the art world. In the end, after consultation with his colleague Nontobeko Ntombela it was decided that the stories would be included in their entirety.

Another issue was how much would get lost in the translation from Venda to English “We tried to leave some of the text untranslated to keep the anecdotes as they are. It challenges that process of consuming and pretending that we understand everything,” says the curator, who is also a writer and editor.

At the exhibition opening, Tale Motsepe from !Kauru Contemporary Art from Africa, which collaborates with the Vhutshilo Arts and Craft Centre, described Mabasa as an artist of “extraordinary talent that most of us have not seen across the world”.

Unfortunately, Mabasa could not attend due to health issues.

“The exhibition is actually a chance for South Africans to see her life’s work. It is a collection of cultural art by a self-taught artist,” Motsepe said. “The artwork of Noria has mostly been celebrated and acknowledged by private owners, institutions and companies. Even in the training, young artists don’t always get exposed to her work until they are in university or already in the field.”

(Supplied by Lucky Lekalakala)

(Supplied by Lucky Lekalakala)Exposure and stifling

In 1985, Noria’s work was included in the exhibition Tributaries: A View of Contemporary South African Art, which featured 111 artists, mainly urban but some from rural areas. It was held in a space made for it in an old market building, which is now the MuseumAfrica.

The exhibition was heralded as marking an irrevocable change in the country’s cultural life and got good reviews. However, some of the artists, such as Johannes Maswanganyi, Dr Phuthuma Seoka, Nelson Mukhuba, Jackson Hlungwani and Mabasa, were categorised as “rural transitional”, basically meaning primitive, based on their geographical background, lack of formal training in art and biographical trajectory.

Dr Same Mdluli argued in research for her 2015 thesis, which looked at the role of exhibitions in the work of African artists, that the exhibition did not necessarily challenge the prevailing perceptions about art from Africa or South Africa. The term “not only imposed a label on the artists but in so doing devised a formula that in the end limited interpretations and other ways of thinking about the particular art form”.

Christian concurs with Mdluli about the legacy African artists are still grappling with today.

“It was an attempt to kind of lock these artists in the past to think that their work is solemnly traditional and therefore not high art.”

Despite the hardships Mabasa, and artists like her, have encountered her success is testimony that her long and illustrious career has been shaped by dreams.

Shaping Dreams runs until 20 November at Nirox Sculpture Park in Krugersdorp, Gauteng.