Kigali Genocide Memorial. Photo: Supplied

“The museum tour begins with a short introduction that includes a brief lesson about Ubuntu, which is Ubumuntu in Kinyarwanda.“

Memorialising Africa’s pain in museums, monuments, and commemorations tends to come across as a performative reenactment of the atrocities that have taken place on this continent. But there is a catharsis that comes with having a tangible representation of the loss, and therefore a place to go when one yearns for closeness to those loved ones who have passed on.

The African continent is filled with dungeons, revamped prison cells, and killing fields that still hold onto the remains of those who were brutally massacred. Most African histories tell a tale of mourning, survival and oftentimes conquering. We keep these stories within walls of buildings so that we never forget but more importantly so that we always remember.

Kwibuka. This word means to remember in Rwanda’s most widely spoken language, Kinyarwanda. Every year, the country commemorates the Genocide against the Tutsis under the theme, Kwibuka. This year when you walk into the Kigali Genocide Memorial you will see a sign declaring Kwibuka 28. It has been 28 years since the genocide.

The Kigali Genocide memorial has become a place where survivors come to have a moment of quiet reflection and simply to visit their loved ones. For tourists, the memorial is a place for understanding and learning about the events of those horrible 100 days in 1994 that took more than 800 000 lives. This is no ordinary museum. It is, in fact, the final resting place for more than 250 000 people who were slaughtered during the genocide against the Tutsis. Their remains are buried on the museum’s grounds under the shade of a beautiful peaceful garden. Each year new remains are brought to the memorial to be buried collectively as more unmarked graves emerge. Walking into the memorial for the first time is incredibly daunting, especially with the foreknowledge that there are people buried there.

Rwanda has more than 250 registered memorials dedicated to the genocide. The more frequented Kigali Genocide Memorial was inaugurated in 2004, 10 years after the genocide took place. The memorial is home to three permanent exhibitions.

The museum tour begins with a short introduction on the values and principles of the memorial. This intro also includes a brief lesson about Ubuntu, which is Ubumuntu in Kinyarwanda. Visitors are then ushered into a room to watch a 10-minute documentary with emotional testimonies from survivors and relatives of victims. This sets the sombre mood for the entire tour.

The African continent is filled with dungeons, revamped prison cells, and killing fields that still hold onto the remains of those who were brutally massacred. Photo: Supplied

The African continent is filled with dungeons, revamped prison cells, and killing fields that still hold onto the remains of those who were brutally massacred. Photo: Supplied

The first exhibition paints a picture of pre-colonial Rwanda with the three tribes Tutsi, Hutu, and the lesser-known Twa co-existing, before German and later Belgian rule. Here there are powerful images of Rwandese men and women wearing their hair in the famous Amasunzu, the Rwandan hairstyle typified by crescent-shaped mounds of natural black hair and proudly clad in their traditional attire. During these simpler times, there were no clear terms used to separate Hutus and Tutsis. They lived on the same land, spoke one language, ate the same food and observed the same religion.

This exhibition further depicts the decline of cohesion between the Hutus and Tutsis. It details the battle for superiority which later resulted in blatant ethnic cleansing. Historically, the Hutus were known to be wealthy while the Tutsis were farmers. It was only during Belgian colonisation, from 1919, that a suggestion of superiority based on ethnicity was promulgated. The Belgians favoured the minority Tutsis. They were so preoccupied with ethnicity that they introduced deplorable acts such as measuring skulls, to determine brain size, and noses. Tutsis were declared by the Belgian colonial government as being superior because they were bigger, taller and lighter in complexion. The next step was to introduce identity cards that specified what tribes people belonged to. The perfect set-up for tribalism.

This exhibition is not for the fainthearted and carries a trigger warning because of the graphic detailing of the ways in which people were killed. You will also see skulls, limbs and large photos of bodies piled on top of each other. There are machetes, axes, and handmade tools that were used by the perpetrators. The exhibits are strikingly graphic in nature and one needs time to pause and process. All the newspaper articles you have ever read about the subject will come alive right before your eyes.

All exhibits are accompanied by short blurbs written in Kinyarwanda, French, and English. This exhibition follows a timeline from the beginning of the genocide which was triggered by the death of Rwanda’s president Juvenal Habyarimana and his Burundi counterpart Cyprien Ntaryamira whose plane was shot down in Kigali on the 6th of April 1994, killing both presidents and 10 other occupants. Their assassination would mark the beginning of the 100 days, from the 7th of April to the 15th of July 1994. The exhibition also documents post-genocide stories and the rebuilding phase. It speaks to the commitment and personal responsibility of the people of Rwanda to make sure that such brutality should never be seen again in the Land of a Thousand Hills.

Wasted Lives

The second exhibition is named Wasted Lives. This section of the museum documents the history of genocides globally. Some of the massacres noted in this exhibition have not been recognised as genocides as defined by international law. This room includes the Herero and Nama genocide in Namibia under German rule, the Armenian genocide by the Community of Union and Progress in the Ottoman Empire, the Cambodian genocide by the Khmer Rouge, the Bosnian ethnic cleansing, and the Holocaust. The number of people across the globe who have lost their lives to ethnic cleansing is staggering. These exhibitions ironically shed some light on how those who survive have to deal with the aftereffects of such atrocities and still exist in the same space as those who carried out the killings.

The Children’s Room

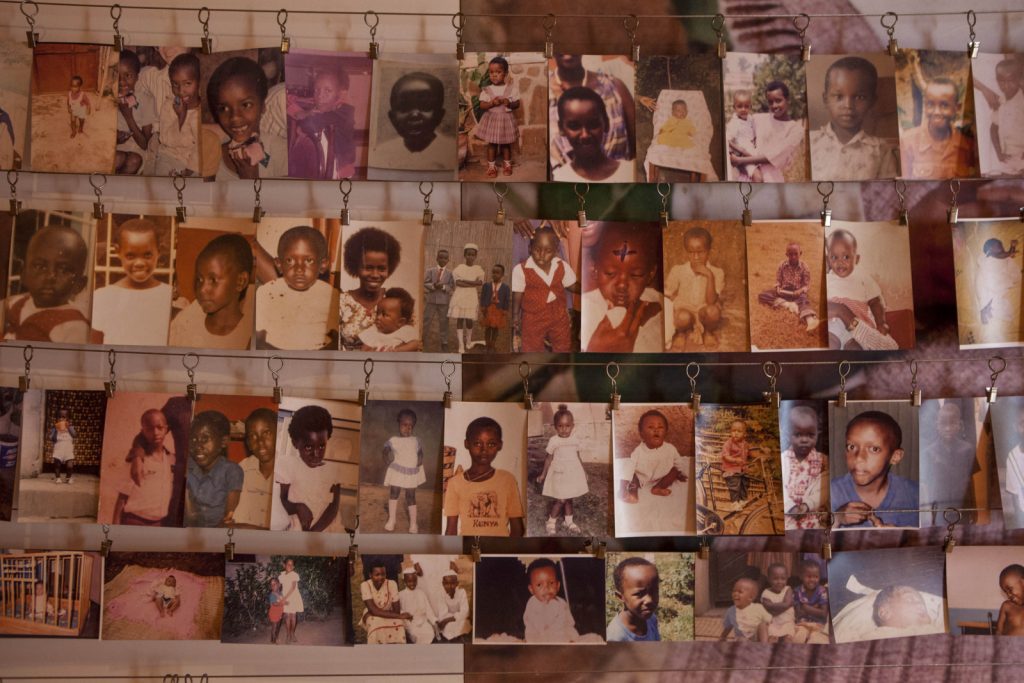

The third and most gut-wrenching exhibition is The Children’s Room. This exhibition consists of large pictorials of children with blurbs referring to simple details like their date of birth and favourite foods. At first glance, you see normal photos of happy babies, toddlers, and preschoolers dressed in their Sunday best with sparkling eyes and wide smiles. As you continue reading, the labels detail how the children were killed. Most babies were snatched from their mothers and killed in the most gruesome ways, as their mothers watched while they waited for their own imminent death. Those whose lives were spared were found nursing from their mothers’ cold bodies. These are the ones who come to the memorial to visit the graves of their loved ones today. The whole room is heavy with pain, but perhaps a more overwhelming emotion is that of anger and shock that the human spirit could be so devoid of compassion that one would kill an innocent child.

At first glance, you see normal photos of happy babies, toddlers, and preschoolers dressed in their Sunday best with sparkling eyes and wide smiles. As you continue reading, the labels detail how the children were killed. Photo: Getty Images

At first glance, you see normal photos of happy babies, toddlers, and preschoolers dressed in their Sunday best with sparkling eyes and wide smiles. As you continue reading, the labels detail how the children were killed. Photo: Getty Images

The Graves – Gardens of Reflection

Once the museum tour is completed, visitors are led to the Gardens of Reflection where about 250 000 thousand people are buried. People come from all over the world and come to pay their respects and lay wreaths on the graves. The graves are laid out under three concrete slabs with a warning: “Please do not step or sit on the graves”, in English and Kinyarwanda, “Ntimukandagire ku mva”.

Another part of the memorial tour is the incomplete Wall of Names, which will remain incomplete because there is no real knowledge of the names and number of people who lost their lives. Even the 250 000 people are not fully identified because their bodies were collected from the streets of Kigali after the genocide.

You may have seen the jerseys of the English Premier League football club, Arsenal, beckoning you with the words “visit Rwanda” and wondered if you should add Rwanda to your bucket list. You might want to go to Rwanda for gorilla trekking and find yourself face to face with Gorillas in their natural habitat, a bucket list item for many. You might even visit Rwanda for business but during your stay, I would implore you to take a moment to visit Kigali Genocide Memorial to pay your respects and honour those whose lives were senselessly taken. When you do visit Rwanda I hope you learn lessons on how to remember the dead as you live so that no one ever tells you to “forget about it and move on”.