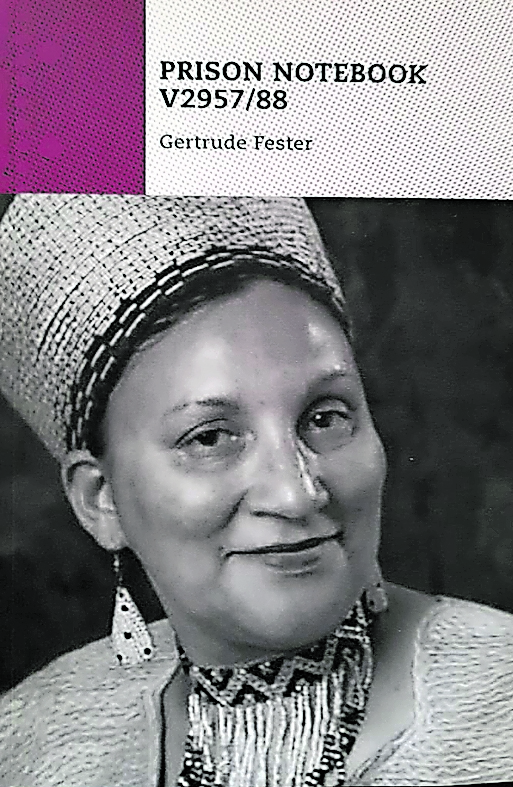

You're not alone: In Prison Notebook V2957/88, 'Professor Gertrude says patriarchy and violence against women is the common denominator that brings women from different backgrounds together to break the cycle of violence. Photo: Getty Images

“If South African women are to participate fully in the global push for gender-inclusive societies, the ruling party’s rudderless custodianship of our democracy may have to be terminated.”

When biographies by struggle icons are released, associates of the subject remind those who were not there during apartheid of the significance of such stories in securing the liberties we take for granted. In Professor Gertrude Fester’s Prison Notebook V2957/88, that responsibility falls to Michael Donen, SC, who dutifully reminds “[t]hose who were not yet born,” in the foreword, “to appreciate what our heroes had to go through so that we could attain the freedoms that we enjoy today.”

When the author, herself, reflects that “the new South Africa that has been in existence for close to 30 years is not the South Africa women in particular, and members of the liberation movement in general, fought for,” then it is not clear what we should be grateful for. Shall we toast the energy crisis that is single-handedly bringing this country to its knees? What about our record rates of interpersonal violence, inherited from men who think they own women and children?

Apartheid ranks up there with Slavery and the Holocaust as one of the worst crimes committed against humanity. So indelibly did it shape the socio-economic landscape of this country that there is barely a difference in wealth distribution between now and then. The youth is grateful that we do not have to carry passes but we are unemployed and living in darkness, with over 81 days of load-shedding this past year.

Liberation stalwarts such as Professor Fester paid an indescribable personal cost for the present we inhabit, so perhaps it is the cadres and comrades of those who were tortured in detention, who should revisit the sacrifices that were made for the country currently under their stewardship.

They may remember the hope that swirled in the air on 27 April 1994 despite the inevitable complications that accompanied the birth of democracy. “[T]he miracle of those peaceful long lines queuing up to vote,” reminisces Prof. Fester, “despite inclement weather in some cases and a shortage of ballot papers, still fills me with awe.” We would soon discover that it is easier to draft a constitution than to implement it. To drive this point home Prof. Fester quotes Giles Pontecorvo’s film The Battle of Algiers: “It’s difficult to start a revolution; more difficult to sustain it. But it’s later, when we’ve won, that the real difficulties will begin.”

If Prof. Fester’s revolutionary politics are rooted in anything, it is the survival of the individual woman. Her mother insisted that her daughters pursue professions even as circumstances tempted them to drop out of school and contribute to the family livelihood. After the passing of the pater familias, the matriarch insisted that she would work her fingers to the bone to keep her daughters out of others’ kitchens.

In addition to a strong maternal figure stoking the fires of social justice, Prof. Fester’s young conscience was kindled by the inconsistent gendered expectations informing child behaviour: “[T]he freedom that boys enjoyed bothered me…there was something ‘wrong’ or repressive…about being a girl;…there were things you could not do and definitely many things that you had to do.” This awakening to the young girl’s first site of oppression – the home – prioritised the personal fight against patriarchy ahead of the liberation struggle playing out in broader society.

Her early politicisation in the United Woman’s Organisation affirmed her commitment to women-centred resistance movements, for the gender dynamics in mixed democratic organisations reflected the patriarchy and ageism in society at large. Women found the environment to be more supportive and empowering in their own institutions, without any of the hesitancy to challenge older men found in mixed-gender organisations. No expert knowledge of feminist theory was required by these women to know that patriarchy was the common denominator in their lives. “It was their own experiences,” Prof. Fester confides, “that afforded them the opportunity…to see that violence against women and men wanting to control women were not individual matters, but rather a problem of a male-centred and patriarchal community.”

No discriminatory experience is homogenous even if it is sexist in nature. Women were (and are) uniformly oppressed but to varying degrees based on race and class. There was no doubt that African women carried (and continue to carry) the heaviest intersectional cross, confined as they were to the bottom of apartheid’s totem pole. They were the ones who were always late for meetings due to the Population Registration Act and a lack of organised transport. Coloured and white women did not have to carry passes, with the latter enjoying regular access to private transport, therefore freedom of movement amongst the races was far from equal, leading to unspoken tensions. White women were known to leave gatherings at the advertised time, even if proceedings were not yet concluded. Complaints about “African time” simmered even though all were aware of the systemic reasons. Nevertheless, women’s organisations did their best to unite them by ensuring that leadership positions were occupied by the downtrodden, with the privileged providing support and resources to the common cause.

A series of questions was posed to Prof. Fester in a 1986 Hilversum radio interview, which any South African would do well to answer today. A selection includes:

- In which ways are conditions for women in South Africa similar or worse than in the 1950s?

- Are conditions for all women in South Africa the same?

- Are women of different races working together? How, and can you provide examples?

- How do you see the future of South Africa?

The femicide rate from 1950 may require a librarian’s degree to pull up but readily accessible contemporary statistics make for nightmarish reading. From October 2021 to December 2022, it is reported that 902 women were murdered. 11 315 rape cases were reported for an average of 123 per day. A 2021 Statistics South Africa report indicates that one in five women had experienced physical violence by a partner. South Africa’s femicide rate was four times higher than the global figure in 2015, and in 2016 a woman was killed every four hours in this country. You do not need a doctorate in criminology to conclude that conditions for women in South Africa are the worst they have ever been.

African women are disproportionately affected by domestic violence due to financial dependence on their partners. As members of the most unemployed demographic, their economic vulnerability dictates that they remain in abusive situations. There is no way gender-based violence can be eradicated without addressing economic inequality. Without financial independence marginalised groups stand little chance of breaking the cycle of violence.

With society as racialised as it has ever been due to the unprincipled, bungling leadership of the ANC, individuals have opted to retreat into racial laagers rather than cooperate on the basis of shared interests. If South African women are to participate fully in the global push for gender-inclusive societies, the ruling party’s rudderless custodianship of our democracy may have to be terminated. “As much as I am a loyal ANC member,” notes Prof. Fester in her chapter on “Above-ground work”, “I believe in dialogue and if we are united in our common end goals/anti-apartheid and working towards a socialist state with no exploitation and capitalism, we should explore means of collaborating.”

How far the ANC has strayed from those ideals.

Prison Notebook V2957/88 by Gertrude Fester is published by the author with support from the Department of Military Veterans and the Human Sciences Research Council, R286.