riting’s on the wall: A mural at a vigil for George Floyd on 25 May , two years after he was killed by Minneapolis police.

Breonna Taylor and Tyre Nichols had the same birthday — 5 June 1993. Both were murdered by police officers in the United States, Taylor in May of 2020 and Tyre last month.

Taylor’s death was one of immense sadness in the recurring and routine murder of black and indigenous people in the US by the police.

Taylor was a black, brown-skinned woman from Louisville, Kentucky, who was an emergency medical technician, a daughter, a sister and a friend. She died in her home as multiple rounds were fired into her apartment as a part of a no-knock warrant at 1am. Her boyfriend fired a warning shot at the police as he heard the door break down but no official announcement it was the police. The officers, as a part of the setup, then unleashed 10 rounds into the couple’s apartment, killing Taylor.

Taylor did not receive medical attention on the scene and on the official incident report filed that day, Taylor’s injuries were listed as “none”, despite being shot five times. Her killers, who were all white, were not convicted of any crimes nor were they immediately fired — one was fired five months later.

The only officers who faced federal and state charges were indicted for “wanton endangerment” of the neighbours in the complex and not endangerment of Taylor or her boyfriend. One pleaded not guilty and was later acquitted.

The attorney general at the time of her case was black conservative politician Daniel Cameron and he announced he would not charge the two officers with her murder.

Chris Carnabuci’s ‘Breonna Taylor’ sculpture in New York in 2021. Photos: Stephen Maturen/Getty Images and Alexi Rosenfeld/Getty Images

Chris Carnabuci’s ‘Breonna Taylor’ sculpture in New York in 2021. Photos: Stephen Maturen/Getty Images and Alexi Rosenfeld/Getty Images

Her death and the death of George Floyd sparked national outrage and international media attention. Twenty-twenty was considered a “year of Black Lives Matter” to those who still need a lynching to be convinced anti-blackness is an issue, let alone the most fatal issue in the US.

At this time, organisers and cultural workers pushed their demands to the front of the dialogue, advocating for the abolition of the police, massive budget cuts for police and military-style policing, more holistic education and, importantly, reparations. Three years later, can we map what has changed with regards to the dignity of black life in the US and globally?

Nichols died five days before national Martin Luther King Jr Day in Memphis, Tennessee, on 11 January. He had moved to Memphis from his home state of California to be closer to his mother and to support his four-year-old child.

Nichols was a dark-skinned black man, 1.9m and 68kg. His family shared he had Crohn’s disease, making it hard to put on weight, resulting in his small stature amid his height.

On the night of the 11th, he was beaten unconscious within three minutes by five black male cops in a traffic stop as a part of Memphis’s street crime-focused police task force, the Scorpion unit.

Nichols allegedly fled the scene when the police pulled him over for what they described as “reckless driving”, “resulting” in their excessive use of force. The beating was so severe that Nichols died three days later in hospital.

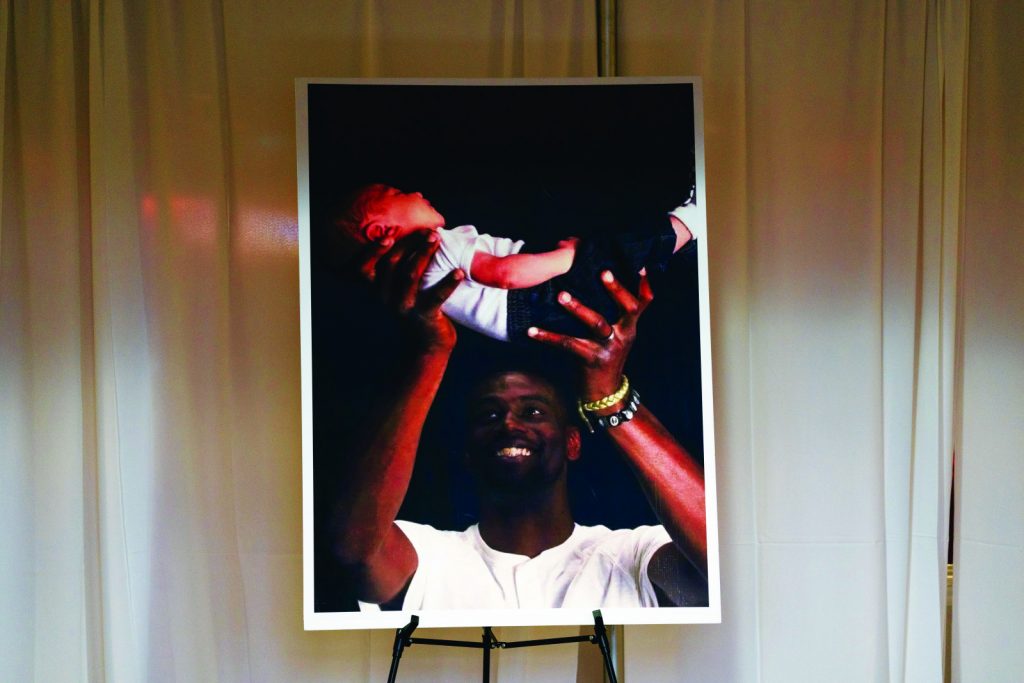

A picture of Tyre Nichols holding his child in the Mississippi Boulevard Christian Church. Nichols died after being beaten by Memphis police

A picture of Tyre Nichols holding his child in the Mississippi Boulevard Christian Church. Nichols died after being beaten by Memphis policeThe Memphis police department has an annual budget of 284 480 825 and is led by Chief Cerelyn Davis, who is a black woman.

Davis described the body-cam footage as “heinous, reckless and inhumane” and all five officers have been fired and arrested on charges of second-degree murder, aggravated assault and aggravated kidnapping.

Their actions were further condemned by the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation Chief David Rausch by stating: “What happened here does not at all reflect proper policing. This was wrong. This was criminal.”

The action and discipline of police officers involved in the death of Taylor and Nichols is most definitely informed by race and gender. Black Lives Matter, as a statement and concept, has lost most, if not all, of its antagonism, and as a result, the concept of it has been gentrified and generally reduced in the white mainstream to address one issue in one specific dynamic: police brutality between white officers (bad apples) and black people, namely men.

However, the murder of Nichols illuminates the inherent anti-blackness and murderous objectives of policing itself, as well as the willingness to fire and discipline black officers where white officers can find themselves never being charged.

James Baldwin in one of his most notable books, Notes of a Native Son, spoke to this power dynamic: “In Harlem, Negro policemen are feared more than whites, for they have more to prove and fewer ways to prove it.”

No matter the officer, policing targets the black body because policing is rooted in racial anxiety and terrorism. Violence is directed at the black body and that attraction of violence is influenced by colourism, fatphobia, classism, homophobia, transphobia and ableism.

So, while Tyre’s murder was committed by black men, it is still a murder by the state rooted in racism and anti-blackness.

The thing about powerful institutions is that they learn how you resist them. It takes small, representative, but hollow, parts of your language and beliefs and incorporates them into its “solutions”. What have we seen instead of the abolition of police? More LBGTQIA, black and women officers and chiefs of police. We also see more specialised versions of policing, i.e. task forces, under the guise of community policing.

Instead of major overhauls to city and state budgets to address racial and class inequality that stems directly from enslavement and lynching and Jim Crow — we get street signs renamed to BLM Blvd.

Instead of a more robust education, we see white people lose their voices in protests opposing critical race theory in their second graders’ education (a concept reserved usually for law and graduate students). We also get precedent-setting “Don’t Say Gay” bills in states like Florida, which ban the teaching or mention of LGBTQIA+ topics.

And instead of reparations, we get multimillion-dollar statutes.

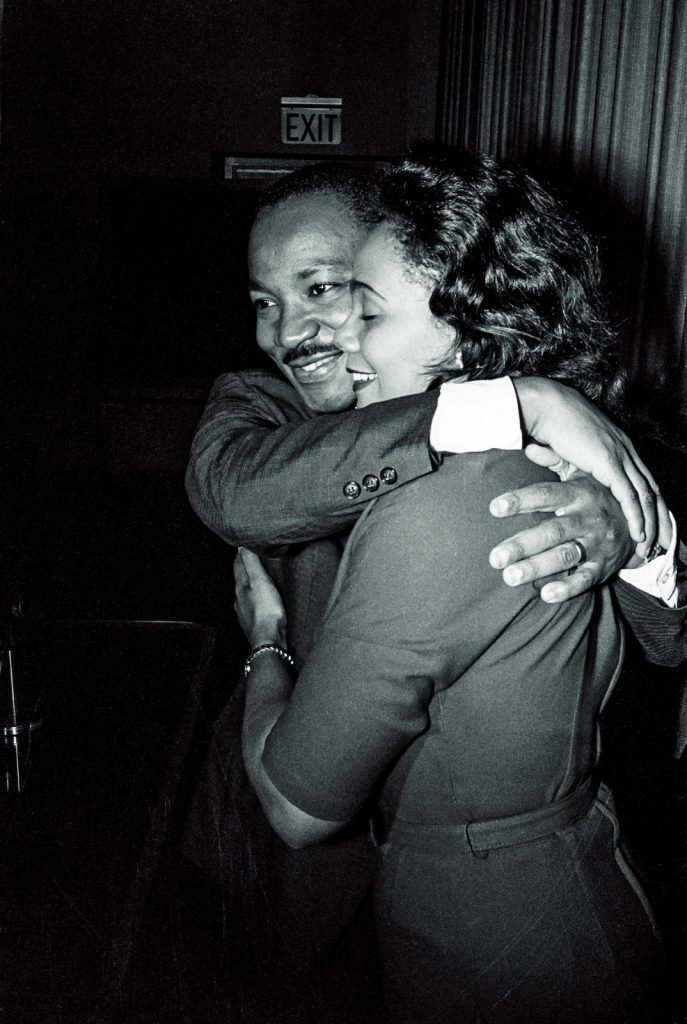

Set in stone: ‘The Embrace’ recalls the hug between Dr Martin Luther King and Coretta Scott King after he won the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize.

Set in stone: ‘The Embrace’ recalls the hug between Dr Martin Luther King and Coretta Scott King after he won the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize.The latest iteration of this kind of poorly timed statue unveiling is a $10 million, 6m bronze statue unveiled in Boston, Massachusetts, titled The Embrace. The Embrace depicts the arms of Martin Luther King and Coretta Scott King, inspired by an image of the two hugging after the announcement of MLK’s winning of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

The couple met, fell in love, and were educated in Boston and the square where the sculpture sits is the same place King held a rally during his civil rights campaigns. The project was created by the City of Boston and Embrace Boston, which is an initiative of the Boston Fund, whose mission is “to dismantle structural racism through our work at the intersection of arts and

culture, community, and research and policy”.

The artist behind the statue is Hank Willis Thomas, who has completed other massive-scale public artworks that function as commemorative pieces. One of his most recent works is a permanent installation at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice titled Raise Up, which is a bronze sculpture depicting an Ernest Cole image of 13 black South African miners being strip-searched for medical examinations during apartheid.

Thomas’s work zooms in on intimate moments. In an interview with Time, he said: “I make a lot of sculptures that are about gestures, inspired by photographs.”

Thomas stated The Embrace was not about MLK as an individual, but about his legacy and all the people who made his work and legacy possible. “It was about his partnership with his wife, that picture where you could see the weight of his body was on her shoulders. I thought that was a powerful metaphor for his legacy. And the way in which she, after he was assassinated, literally carried it on her shoulders.”

The statue was unveiled on 9 January to mixed reviews. Coretta Scot King’s cousin, Seneca Scott, penned an essay in Compact Magazine, writing that the sculpture was performative of the “woke” left and would contribute “few, if any, tangible benefits to struggling black families”.

On the conservative side, you have Fox News’s Tucker Carlson (loosely) debating the legitimacy of “abstract art”, ultimately concluding the statue wasn’t of value because most people “couldn’t get it”. On the left, we saw criticism that was more concerned about the obsession and sanitising of MLK’s legacy in a country that still disproportionately kills and imprisons its minority black population.

Commemoration is a complex subject, and the intentions can change depending on which angle you look at the piece from.

Commemoration, or the act of using a physical structure to remember a person, people or moments, can have complicated repercussions. While the impulse to honour someone in a literal and tangible way appeals to our most primary emotional responses, there can also be a sense of finality that comes with this. Now that a statue of MLK or Nelson Mandela has been erected, this demonstrates that the worst of what they worked against is behind us and there’s some hopeful future to see ahead.

Many critical thinkers and cultural workers have raised this point — that certain eras of human catastrophe get classified as just that, human catastrophe. All the enduring legacies of catastrophe, such as anti-black racism; lack of land and capital ownership; medical experimentation and lack of human dignity, extended to black, indigenous and racialised immigrant citizens, do not get remembered in the same way.

Importantly, the perpetrators of catastrophes that happen to black and indigenous people never quite get remembered specifically; it’s often a great tragedy that happened out of the sky a very long time ago.

In the case of The Embrace, there is an ongoing un-ironic irony that the US is a master of performing. The same country that stalked, harassed, built surveillance technology models around, and ultimately murdered, Martin Luther King has erected a faceless statue that is focusing on the love between him and his wife.

His politics of anti-war (Vietnam), his own contempt for his country, which he called “the great purveyor of violence”, and his work on the poor people’s campaign, uniting sanitary workers across racial grouping that ultimately got him killed, is still widely untold and under-taught.

While the romanticisation of the couple indeed brings a human element to the memory of MLK that goes beyond the “I have a dream” soundbite, it simultaneously presents the confounding question of love. Can love conquer? While liberal America — Kenya Barris and Shonda Rhimes — seem to think so, there’s another conversation to be had about symbolism dominating.

This conversation is about countries like the US and South Africa that rely on routine symbolism to mask their anxiety and ongoing bleeding and perpetuate love as the ultimate, flattening goal.

Black History Month began as Negro History week, created by Dr Carter Woodson in 1926. He initiated it as a part of his founding organisation Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, which is now the Association for the Study of African American Life and History.

Carter, author of numerous books, including The Mis-Education of the Negro, stated that black history was “a negligible factor” in the narrative of the US, and Negro History Week offered a way for black people to begin to learn and appreciate and build a rich history. Negro History week was declared a national month by all presidents after the move made by Gerald Ford in 1976.

And while its intention was never antagonistic, Black History Month, which follows MLK Day (which only exists thanks to Scott King), has been weaponised by mainstream systems with a month of performance.

Black History Month offers black people a chance to create, imagine and learn from a perspective that doesn’t have to do with whiteness or solely slavery or Western measures of success and contribution.

However, while statues of MLK get unveiled, a brutal murder of a black man by militarised police forces takes place just days before. Three months after 2020’s Black History Month, Taylor is killed in her sleep. Iyanna Dior, a black trans woman, was beaten at a petrol station in Minneapolis by a mob of black men at the time of protests for black lives.

With every year BHM rolls around it emphasises how little things change, even though we are all buying black and white people are reading Ibram X Kendi extra closely. Black History Month has come to have anxiety about it, where a nation that outwardly hates its black and indigenous citizens must somehow put together a campaign, a reading list, a mutual aid fund or a donation list to address the violence for 28 days. Just like when you try to walk against the wind, America clumsily goes against its own foundation, the violation and degradation of black people, for February.

The gnawing reminder of stagnancy makes it all the more difficult to understand how to make sense of your own life and country.

The statue of Nelson Mandela at the Union Buildings in Pretoria (left). Photos: Robin Lubbock/WBUR and Alexander Joe/AFP/Getty Images

The statue of Nelson Mandela at the Union Buildings in Pretoria (left). Photos: Robin Lubbock/WBUR and Alexander Joe/AFP/Getty ImagesThe rainbow nation — Nelson Mandela’s nation of rainbows and miracles, South Africa — is arguably built on symbolism as a means of forged and feigned progress. Everything from the South African flag to TV show Come Dine With Me promotes a sense of racial unity and sharing of culture and land. However, we know very little has tangibly changed since the mid-1900s — safe and clean water access is denied in black and rural areas of the country, and there are water cuts in townships. Land ownership is still disproportionately held by white South Africans and foreigners.

When the Day of Reconciliation or the anniversary of the Marikana Massacre comes around, there are more atrocities to list and more lives lost to problems that have supposedly ended and are packaged up at the Castle of Good Hope or the Apartheid Museum.

As routine as remembrances are, so are the catastrophes. Black History Month is hard to celebrate when the gun, the boot and the nation are pointed at you, leaving you with very little to embrace.