Depth of feeling: Zanele Muholi’s photographs ‘Manzi III’, from a series which shows them swimming in the Atlantic Ocean

It is inevitable really that the professional divorce between artist Zanele Muholi, who is ranked 28 in Art Review’s Power 100 list of the most influential people in art, and pathfinder gallery Stevenson, should be a talking point.

For nearly two decades, starting in 2006, Stevenson represented Muholi, helping broker their stratospheric rise from Market Photo Workshop graduate to international figurehead.

Muholi, an alumnus of the Venice Biennale and Documenta (twice), is still processing the divorce. In a recent interview they explained that their working relationship with Stevenson ended late last year.

“I was retrenched by Stevenson,” said Muholi. “Stevenson said they can’t work with me any more. It is not like I wanted to leave. I have been with Stevenson all my life. But there are no bad energies whatsoever.”

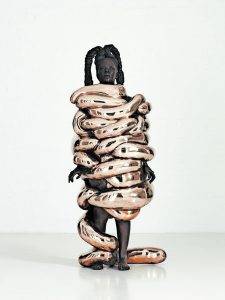

‘Umkhuseli (The Protector)’ by Zanele Muholi.

‘Umkhuseli (The Protector)’ by Zanele Muholi.

The parting of ways has not seen any slackening in Muholi’s legendary energy. Now resident in Cape Town again after a decade’s absence, Muholi has spent the first half of the year pursuing three-fold activities as artist, activist and teacher. The vocational nouns are not easily separated — Muholi is a hyphenate being.

In April, Muholi visited Expo Chicago, a prominent American art fair, to show a monumental sculptural bust in bronze and launch a book pitched at young adults. They also gave a private talk to art-interested high school students from Chicago’s deprived South Side. The talk saw Muholi field no-fuss questions on a host of topics.

“My photography is of LGBTQI people, black lesbians, and speaks of issues of blackness, the politics of blackness,” said Muholi about the relationship between activism and photography.

“It allows people to occupy a space where previously people weren’t given a platform. We need to be heard and understood. If history is for everyone, ours is important too.”

Muholi singled out author, poet and activist Sindiwe Magona as a key influence. “Her work speaks to me.” But it was a question about apartheid that got the lengthiest response.

“The question goes back to you or any other young person here. What work is being produced during a period of gun violence and racist spaces in America? “What does it mean to live in Chicago and Braddock in Pittsburgh in this minute, where a lot of young people are displaced?”

Muholi’s response draws from personal insight. A frequent traveller to the US, in 2013 they showed 48 portraits from Faces & Phases (2006-), an ongoing photo project with black lesbian subjects, at the prestigious Carnegie International in Pittsburgh.

“Do you get what I am saying?” Muholi continued. “This is just to challenge you as a young person to look at where you stand and ask yourself: ‘Where am I? What song can I produce out of this experience and the experiences of those around me? What sort of experience can I come up with knowing that not everybody is written into American history? Why do we have Black art in America when there is no problem? Why do we have Black Lives Matter and Me Too?’ These are the questions young people need to respond to when teachers bring up apartheid.”

After the talk, Muholi showed off their new book Connect the Dots. Produced in an edition of 250 copies, the workbook features dot-to-dot images based on Muholi’s imaginative self-portraits from Somnyama Ngonyama (Hail, the Dark Lioness), a work-in-progress series started in 2012. Pages were torn from the book and shared with students, who completed the drawings.

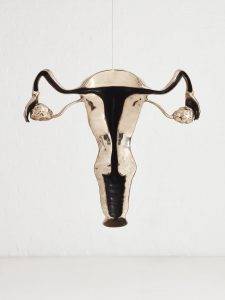

‘Umphathi (The One Who Carries)’ by Zanele Muholi.

‘Umphathi (The One Who Carries)’ by Zanele Muholi.

Southern Guild, a Cape Town art and design gallery, helped Muholi with the logistics of the talk and book launch. Southern Guild also showcased Muholi’s large sculpture, Muholi III, in its fair booth, alongside stoneware pieces by Andile Dyalvane and Zizipho Poswa.

“My experience of working with Zanele is that there is such a depth of passion and poignancy to everything they are interested in,” said Trevyn McGowan, co-founder of Southern Guild, after the talk. “There is no artifice; you are really seeing the core.”

The loose association between Muholi and Southern Guild (the gallery does not formally represent the artist) culminated in a solo exhibition at the latter’s V&A Waterfront gallery. The self-titled exhibition, which closed earlier this week, featured 46 photos, most of them self-portraits, and seven bronze sculptures. The photos were priced, in dollars, between R380 000 and R568 000, and the bronzes offered at between R1.5 and R5.3 million.

A photo series titled Manzi (2022), which shows Muholi joyously bathing in, and breaching from, the cold Atlantic Ocean, captures something of their current mood.

But the Southern Guild exhibition also showed Muholi’s unyielding commitment to making what I call “instructional art” — art oriented to bluntly addressing social issues.

Around 2016 Muholi started to experience swelling in their abdomen accompanied by heavy bleeding. It culminated in a diagnosis of fibroids, non-cancerous growths that develop in or around the womb, and a surgical intervention in late 2016. The experience was both traumatising and enlightening.

In a wall text placed near the exhibition’s centrepiece, Umphathi (The One Who Carries, 2023), a larger-than-life bronze sculpture that monumentalises a tattoo of a uterus on their left shoulder, Muholi expanded on the work’s relevance.

“People have asked me, ‘How is your uterus art?’ But this is no longer about me, it is about every female body who has existed in my family and never imagined these dreams were possible.”

The wall text invoked apartheid history, stating that “bantu education” skipped over sex education.

“Together with other sinister apartheid laws, this [act] was carefully crafted to decimate the Black person. If there had been education about sex, teen pregnancies would not have become a pandemic.”

‘Bambatha’, by Zanele Muholi.

‘Bambatha’, by Zanele Muholi.

Muholi received counselling about their body’s transition to puberty from their teen sisters, not their mother. “She was at work, raising another family’s children.”

There is no doubting the narrative torque of the sculptures on view. They unfailingly instruct. Take the large resin, marble dust and bronze Madonna sculpture titled Umkhuseli (The Protector, 2023). Muholi was brought up Catholic. The church condemns homosexual acts.

“Gay people have spiritual needs too, they deserve marriage ceremonies and funerals and places to worship,” elaborated Muholi, adding she now attends Victory Ministries Church International in Durban, where the artist maintains a studio.

“This is where I can express myself freely without fear of persecution from those whose spiritual and personal beliefs differ to mine.”

The persuasiveness of Muholi’s explanations do not defuse a lingering doubt I have about the sculptures.

In September, as the relationship between Muholi and Stevenson moved into its terminal phase, the Radisson Red in Rosebank launched a year-long exhibition of Muholi’s photos and sculptures. Muholi’s likeness appears throughout the hotel, on large canvas prints and in a series of fibreglass sculptures. The latter pieces, all executed in black, are far from convincing.

Cheaply produced, they show little technical facility or thinking in the round. They seem to perpetuate the cult of personality I saw as underlying Muholi’s artist empowerment project Ikhono LaseNatali, which manifested as an exhibition at Cape Town’s A4 Arts Foundation in 2019.

But this is simply a curmudgeonly critic’s opinion. Handwritten on a card placed next to a completed drawing from Muholi’s Connect the Dots workbook at Southern Guild, a visitor wrote: “Amazing work of art with phenomenal messages.”

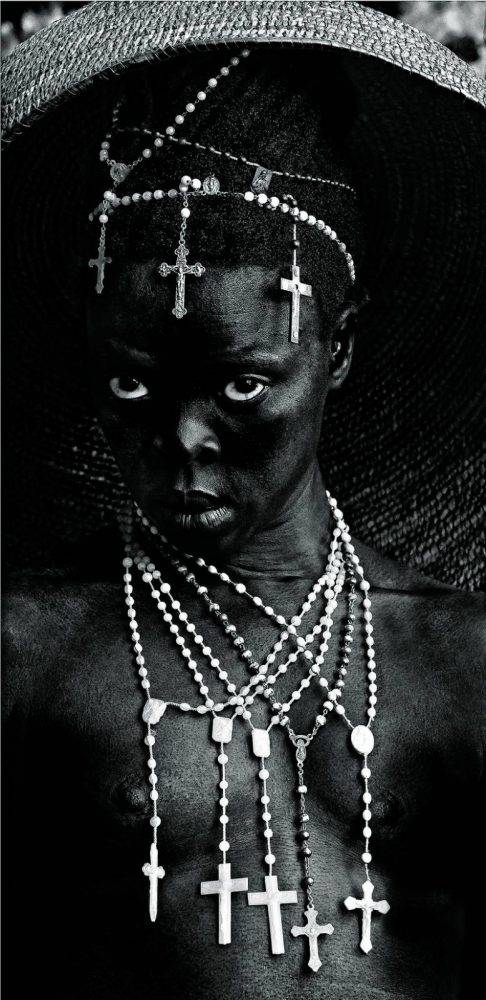

‘Nomthandazo (The One Who Prays)’

‘Nomthandazo (The One Who Prays)’

Among the works on view in Rosebank is an expressionless study of Muholi, wearing a hat and bow tie, with their arms folded. It is the basis of Muholi III, which travelled to Chicago in April. The upgraded bronze work had mixed reviews. Artnet described the sculpture as “stunning and unexpected”, while Hyperallergic thought it “eye candy”.

When I met Muholi in June, the artist described how some viewers mistook the androgynous portrait bust to be a study of their father or brother. The process by which the sculptures were produced clarifies a source of the ambiguity.

“These are photographs. The sculptures are made from 3D capturing. They are moulded and resined.” In other words, the sculptures are rendered rather than wrested.

Whatever one makes of Muholi’s pivot to sculpture, which contributed to upending a long-standing professional relationship, one thing remains clear. At 51, Muholi is as blissfully alive and insistently present as the young, unrepresented activist-photographer who two decades ago displayed their intimate photos of black lesbian practices on a pavement at Joubert Park in central Johannesburg. Hallelujah.