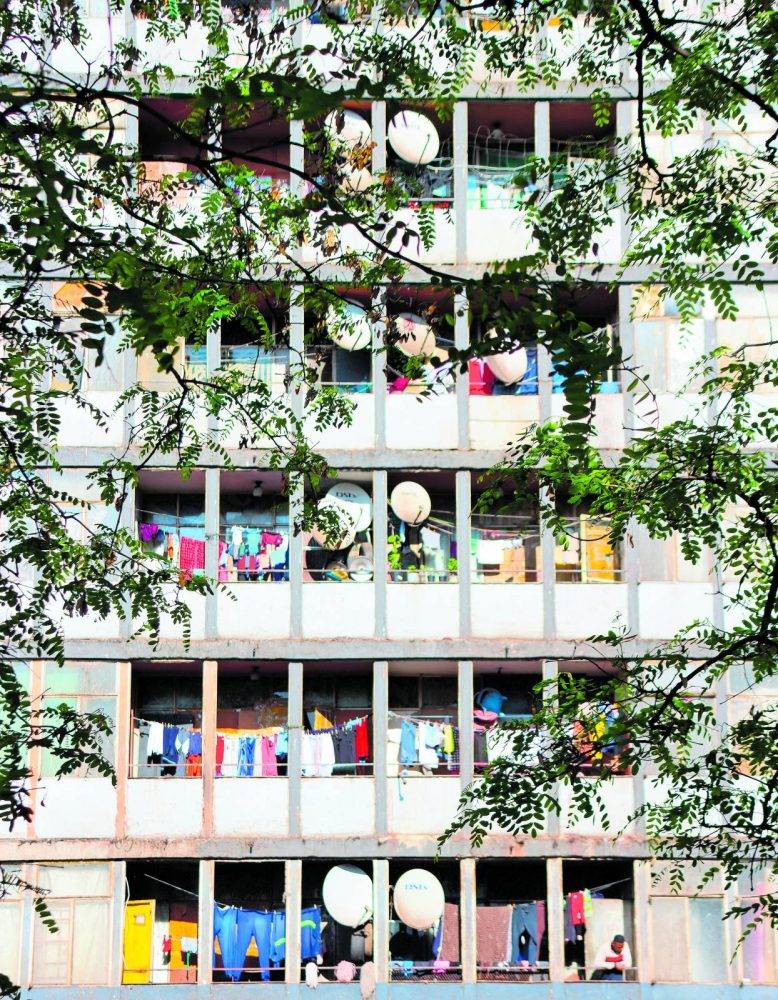

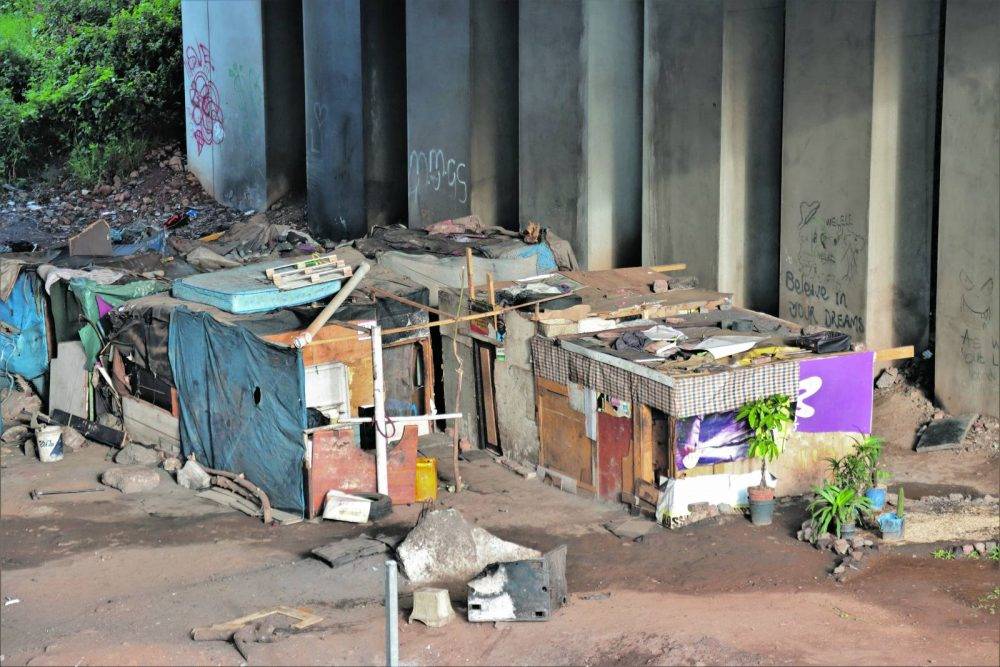

Urban but not so mythical: Tim Haynes’s book ‘Hollow City’ has evocative photographs of the state of central Joburg by the writer himself, his son Ciaran and David Edwards. Photos: David Edwards

The myth of Egoli holds so much water in Africa that thousands still make the long trek south in search of riches.

Many end up living in its rotting centre and I’ve often wondered what circumstances they fled, to not turn around and head home once they’ve had a taste of it.

It’s common knowledge to the folk who live here that Joburg’s inner city has long been abandoned by investors, the province and the city council. From a quick drive through it — or even past it, the route most well-heeled Joburgers prefer to take — it is immediately apparent that most of it has become a Stygian nightmare, a set for the next Mad Max dystopia.

Why, then, would anybody choose to write a book about it?

Tim Haynes, the author of Hollow City: Stories of Hope and Horror from Joburg’s Inner City, has already written three books about his life. “Given my autobiographical bent, it was natural that, once I felt I had enough stories arising out of my involvement in the inner city, I should start writing.”

Since 1994 he has been involved in property development, first as a consultant in government inner-city housing in Joburg and then as a partner in a firm offering plumbing solutions for the affordable housing market in Southern Africa.

“This book project has been especially important to me because my life, and the lives of my family, have been intricately involved in the fortunes, or otherwise, of the city,” Haynes says.

“We are close to our employees and our tenants and feel a sense of responsibility for their lives, a feeling clearly not shared by politicians. Were they to share that sense of responsibility, the state of the city would not be what it is.

“I believe that the more people know and understand the story of the city, the more pressure might be brought to bear on city management to restore the inner city to a healthy and habitable environment.”

In his dedication, Haynes makes this sentiment even more explicit: “Old Joburg and [its] environs have been turned into a dustbin of humanity, a place where even rubbish is not removed. This book is written to goad those who govern into doing what they should.”

Hollow City — which derives its title partly from TS Eliot’s famous poem Hollow Men — is an atypical book in many respects, including its size and the choice of paper.

Portraits of lives: Tim Haynes hopes the awareness raised by his book will spur the city management to restore the inner city to a liveable state. Photos: David Edwards and Derek Davey

Portraits of lives: Tim Haynes hopes the awareness raised by his book will spur the city management to restore the inner city to a liveable state. Photos: David Edwards and Derek Davey

Measuring 17.9cm by 23.8cm (a size Wikipedia defines as “Super Octavo”), and printed on glossy paper, it resembles a graphic novel more than a book.

Haynes says that the book designer and printer told him that the thicker the paper and the glossier, the better the reproduction of the pictures would be.

Most of the photos, of which there are nearly 150, were shot by David Edwards. The rest were shot by Haynes himself, or by his son Ciaran, who has become an integral part of the family business.

The author says during the writing of the book, he went to an exhibition of Edwards’s photos and discovered that the work mirrored his own, which birthed the collaboration.

At times the photos match the content but often they don’t. The majority of the shots are bleak: piles of trash, dilapidated buildings, prostitutes prowling the pavements. Sensitive viewers be warned — there’s a burning man (no relation to the festival) and a hanged man.

There are a few that provide balance by reflecting joy, community and the indomitable spirit of the city centre’s inhabitants.

Some images fill a double spread; others are small and pasted across each other. Hollow City is as much a photo album as it is a memoir.

Each chapter is an autobiographical story from Haynes’s life and his work in the city centre. The stories are a potpourri of cultural and class clashes, with a generous dash of race and gender stirred in.

In the first chapter, Haynes is on the phone to the landlord of Finsbury Court, advising him to cut his losses and sell the rapidly disintegrating building.

Gunshots are so common they do not even register for the tenants who gather for a meeting, chaired by a woman from rural Zululand who rose from cleaning woman to head of the tenants’ organisation.

A power struggle takes place between two tenant factions, which ends up involving the taxi mafia and, briefly, the police. One man dies.

And so the stories go.

Refilwe Gets a Beating outlines how a woman is savagely whipped — by another, larger woman — for “looking at her man”. Another details a drunk with bits of his ears missing, who insists on being employed by Haynes and later loses his marbles and stabs one of his employees.

Haynes is threatened with being hauled up in front of the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and the Housing Tribunal on several occasions.

I kept wondering how this mlungu managed to deal with the stress of it, the yawning chasms of race and class he had to cross for all those years.

When I asked him, he replied: “The gulf between all race groups, across the country, is huge. However, in Joburg city, it has narrowed more than in most places.

“Failing to understand culture and background is not as important as having a healthy respect for people and their differences. And a good sense of humour often trumps misunderstanding.”

As the subtitle of the book is Stories of Hope and Horror from Joburg’s Inner City, I inquired if there were any success stories that he could tell about in the business district of our “world-class city”.

“The first stories in the book describe the failures of the Government Housing Policy in the CBD. After 1994, there was no plan. All that happened was housing subsidies were extended to beneficiaries.

“In the city, these were put into legal entities through which blocks of flats were purchased. Some of the blocks were sectional-title buildings but the ‘new owners’ never acquired ownership. Almost without exception, these projects failed.

“Throughout the country, the government has shown itself to be reluctant to hand over title deeds.

“It was in this context that the private and semi-private sector became active in inner-city housing, either purchasing or repurposing existing residential buildings, repurposing commercial buildings or constructing new ones. These were initially mainly intended for affordable rental and, more recently, student accommodation.

“In an environment of dysfunction, new systems of management had to be formulated to cope with the chaos and anarchy.”

Haynes lists a few notable successes that fall outside of what is called “affordable housing”, including The Maboneng Precinct, Jewel City and Nando’s, which built its world headquarters in Bez Valley, and then added the entire block of Victoria Yards next door.

Financial assistance is a huge obstacle for developers, he stresses.

“The banks’ redlining of the city remains in place even though, paradoxically, the four major banks keep their head offices in the CBD … The city council and the province have failed spectacularly in all areas. Until this is completely reversed, new developers will have no appetite for the risk involved in investing in the inner city.”

Haynes predicts a bleak future for the city’s centre. The provision of services; the maintenance and upgrade of infrastructure; prudent financial management; crime control — all of these and more, which are necessary for a turnaround, “are way beyond the capability and political will of the present administration”.

But, he says, his book is selling well, particularly in Cape Town and Durban. Perhaps Joburgers don’t want another reminder of the “vrot kol” their plush suburbs surround.

People still come to the fire-blackened city centre with hope in their hearts. Shacks are erected inside and on top of hollowed-out buildings that long ago lost services such as power and water; waist-high cardboard homes line the potholed streets and murky freeway flyovers. Inner-city residents fill buckets from dribbling fire hydrants, burn whatever they can find for heat and compete with chickens to scratch a living from the manicured rubbish, as taxis laden with shoppers jostle past.

Edwards observes: “Joburg has been transformed but possibly not in the way that the politicians announce it to be. It’s never been as vital. It’s become a diverse city bursting with life, where people need stamina and resilience to meet their basic needs.”

For all its gaping wounds, Egoli’s city centre is still breathing.

Tim Haynes’s Hollow City was self-published this year.

His website for the book can be found here.