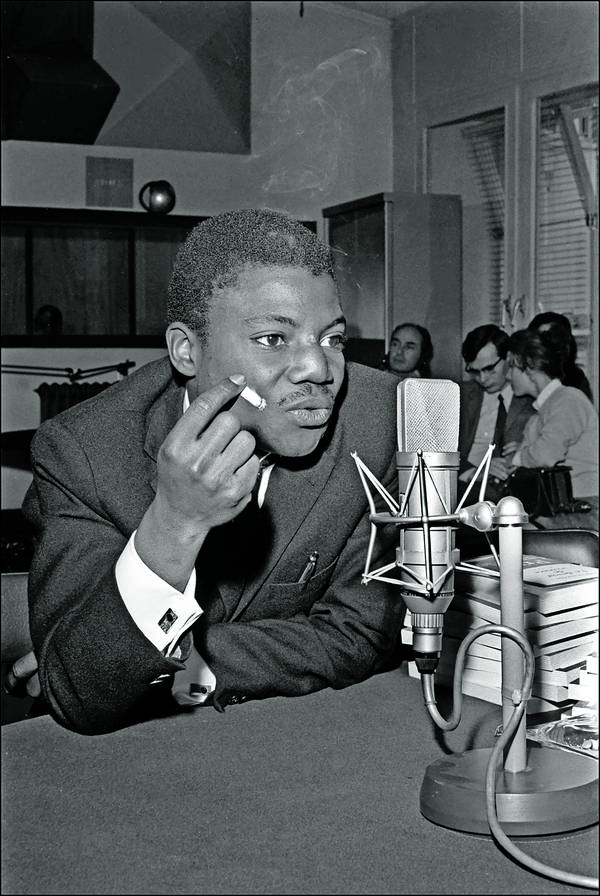

Secret memory: The Senegalese writer and France’s Prix Goncourt winner Mohamed Mbougar Sarr (above) wrote a book inspired by the life of the late prize-winning Malian novelist Yambo Ouologuem, who was most likely falsely accused of plagiarism.(Photo by Eric Fougere/Corbis via Getty Images)

In 2021, Mohamed Mbougar Sarr’s ambitious novel, La Plus Secrète Mémoire des Hommes, won the most prestigious French gong the Prix Goncourt — a first for sub-Saharan Africa.

The novel, translated into English as The Most Secret Memory of Men, is itself dedicated to, and inspired by, the life of the Malian novelist Yambo Ouologuem — the West African writer who became the darling of the French literary establishment when his novel Bound to Violence, published in 1968, won the Prix Renaudot.

But infamy and controversy followed not long after when Ouologuem was accused of plagiarising the English novelist Graham Greene and the French writer Guy de Maupassant.

At the time, his defence was his publishers had made unauthorised changes to his manuscript published in French as Le Devoir de Violence, removing quotation marks where he quoted the European writers (an account corroborated by the British editor Kaye Whiteman who claimed to have seen the manuscript); he also said that he hadn’t signed off on the version sent to the printers.

The episode so disillusioned Ouologuem that he turned his back on literature altogether, even returning to the Islam of his youth. He went back to Sevare, in Dogon country, northern Mali, where he lived until his death at the age of 77 in 2017.

For decades, many wondered what had happened to the brilliant author of Bound to Violence, a novel exploring homosexuality, pre-colonial violence and the complicity of African Muslims in the Atlantic slave trade.

Ouologuem was considered a heretic and outsider for several reasons: his iconoclastic novel which the label of “African literature” didn’t quite fit, his espousal of the view that the internecine violence in Africa before the arrival of whites contributed to our subjugation, and his caustic dismissal of African Americans then using Islam to trace their roots to Africa.

If the boxer Muhammad Ali and others in the Nation of Islam closely read the Qur’an, Ouologuem argued, they “would have found in it a code defining the status of slaves, for the slave trade is inherent in Islam. It is as if a Jew — because he didn’t know his own history — referred to Hitler in order to discover his own identity.”

In the 1970s, when the Nation of Islam was a potent force in confronting the racism of white America, this nuanced view was not universally popular.

It was an American intellectual, Christopher Wise — whose edited book Yambo Ouologuem: Postcolonial Writer, Islamic Militant came out in 1999 — who helped us understand Ouologuem’s reasons for abandoning literature.

In his essay, In Search of Yambo Ouologuem, carried in a 2007 Chimurenga issue, Conversations with Poets Who Refuse to Speak, the reclusive writer met Wise and spoke, his first interview in decades.

In the introduction, Wise asked pertinent questions: was Ouologuem “a fraud” and “a mere plagiarist?” Could Ouologuem be reduced to “an apologist for the French?” Was “he a fierce critic of Islam” or “its staunchest defender?” Was “he a charlatan or a great genius? A madman or saint?”

All the questions Wise threw up about Ouologuem would have been enough to go on a memorable literary ride but Mbougar Sarr, the Senegalese writer born in 1990, goes way, way beyond the remit of these questions to conjure up a staggering story of immense beauty about a fictional writer TC Elimane and his forgotten masterpiece, The Labyrinth of Inhumanity.

Although Ouologuem is the inspiration behind the figure of Elimane, another was the Chilean writer Roberto Bolano’s novel The Savage Detectives, from which Mbougar Sarr got the title of this novel.

Malian novelist Yambo Ouologuem, who was most likely falsely accused of plagiarism. (Photo by Yves LE ROUX/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Malian novelist Yambo Ouologuem, who was most likely falsely accused of plagiarism. (Photo by Yves LE ROUX/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Another could have been the Guyanese writer Edgar Mittelholzer’s memorable novel My Bones and My Flute about a “cursed” manuscript written by a Dutch slave owner, which set off the sound of a flute in the ears of whoever touched it.

Almost all the critics who reviewed The Labyrinth of Inhumanity — good or bad — or accused its author of plagiarism, either committed suicide (six died by their own hands) or died suddenly.

It seems Elimane mastered the darker arts from his sangoma uncle, who used to torment his adversaries until they were driven to commit suicide.

(You have to admit those were surreal times, when the critic was felled by the darker arts, rather than just trolled on social media).

In this universe in which books were a matter of life and death, madness and suicide, it’s fitting that a character in The Most Secret Memory of Men declares: “We have to behave as if literature were the most important thing on earth …”

While still in high school, Diegane Latyr Faye, our principal narrator, hears of a novel by a certain TC Elimane, a Senegal-born writer who moved to Paris in the interwar years and where, in 1938, he published a novel, The Labyrinth of Inhumanity.

When it came out, the novel had as many fans as it had detractors. To some, Elimane was a “Negro Rimbaud”, certainly “with a touch of genius”, while to others he was a shameless plagiarist whose “bleak book [also] nourished the colonial vision of Africa as a place of darkness”.

The Labyrinth of Inhumanity’s sin, as one critic wrote, was it revealed “too many of its borrowings”. Being a great writer, perhaps, is “nothing but the art of knowing how to conceal one’s plagiarisms and references …”

When Faye was growing up, the novel was long out of print, and information about it and its author scant. There were not even pictures of Elimane around.

A professor of African literature in Senegal dismissed the novel as one written “by a eunuch god” that a had a “fleeting existence in French letters”. Pilloried in the mother country, France, dismissed in his own country, Senegal — what a tragic fate.

“Elimane had been erased from literary memory, but also, it would appear, from all of human memory, including that of his compatriots …”

After failing to find much about the book beyond its first sentence, the narrator later moves to France for his studies. He tries his hand at writing and his “little novel”, Anatomy of the Void, comes out via a small press but sells only 79 copies.

It was in the little novel’s wake that, by chance, the narrator met the Senegalese writer Mareme Siga D, universally derided in her native Senegal, whose base is Amsterdam, and who is to have the biggest influence on his writing career.

It was in a Paris bar that they met. Not only did Siga D know of Elimane but possessed an actual copy of The Labyrinth of Inhumanity — the ghostly and forgotten book was a living, breathing thing, after all.

From this most random of meetings, the narrator, like a literary sleuth, constructs an epic story that takes in the most important moments of 20th century history: white presence in Africa and the establishment of schools on African soil into which young Africans, including Elimane, were lured (“the white man came and some of our bravest sons went mad”); World War I and the Senegalese tirailleurs, African riflemen from France’s colonies who fought in the frontline trenches (Elimane’s father fought in World War I); World War II itself and the fate of the Jews (the publishers of The Labyrinth of Inhumanity were Jews).

In these great historical currents, the African is not just a bystander, but an active participant.

But all this history is just background noise, for the overwhelming story at the heart of this novel — the quest for a lost book, quest for a lost innocence, quest for an origin story, quest for a father, quest for an ancestor, quest for revenge and a quest to not only leave home but also erase all traces of home.

The novel is itinerant, eschewing a single pivot and one staging ground. It’s set in Europe but it’s also set in Africa. It’s set in Amsterdam and Paris but also in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where Elimane, exiled from his motherland, found new compatriots in writers such the Polish modernist Witold Gombrowicz, who was also estranged from home.

What Mbougar Sarr did with this novel reminded me of something else. I don’t know about in Senegal, but some Africans in the 1890s in colonial Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) considered writing and reading as close to divining. That it was priests who taught people to read and write added to the mystique of the written word.

That you could take this stick — pencil — scribble a line or two on a piece of paper, pass it on to the next person who would immediately decipher the message, was akin to throwing bones. This piece of paper, so they said, sees and speaks.

Likewise, The Most Secret Memory of Men has raised this forgotten novel, The Labyrinth of Inhumanity, to the level of a mystique, even an artefact of witchcraft, an instrument to kill off the critic.

Mbougar Sarr has not only done that, but also elevated the written word to a rarefied zone — the country of literature as an autonomous state of being and fiction as a way of being free.

From wherever he is in the world of the departed, Yambo Ouologuem must be wearing the smile of a plagiarist who has been exonerated.