Walkabout: Majak Bredell talks about one of the works at her exhibition Interconnections at the White River Gallery in Mpumalanga.

The White River Gallery in Mpumalanga is behind brick walls crawling with creepers, covered in dry autumn leaves.

It’s reminiscent of a Victorian garden — but with a South African charm, with curio shops tucked into the corner, while sculptures of steel and iron loom large.

The gallery is displaying the work of South African artist Majak Bredell, which is a feast for the eyes.

The colourful figures and geometric shapes on paper, mounted on the white walls, are enticing.

They raise questions about the artist’s interest in figures, especially the human form.

The work is symbolic and it’s interesting to view and contemplate.

“I am the catalyst — my artwork is the catalyst that opens the viewer to the thoughts and feelings that come up for yourself when you look at the art. To me, that is why I make art,” Bredell told the Mail & Guardian at a restaurant in Pretoria.

Her exhibition Interconnections is divided into two parts: Dialogues & Analogies and Levels & Layers.

At the centre of this intricate world of conversations and connections is the story of humankind and Earth, which has developed out of her previous works, which touched on similar themes.

“My earlier works worked on the idea of restoring a sacred mirror for women — where women can see themselves reflected by the sacred — and what is the sacred female? It’s Goddess. It’s not God with boobs.

“It’s a Goddess with a cunt and a womb. That’s really what’s at the bottom of my work — restoring that imbalance.”

Bredell said her new work celebrates the many levels and layers of interconnections and interdependencies between humanity and the earth that supports us. She echoes the theories of eco-feminism that regard the earth as a living organism but also speaks to its relationship with women.

Through themes of nature, she relays that we are not only products of the sky and the stars, but we are also bound to the earth — to Mother Earth — and through this analogy and understanding of the world, she suggests that, if we regard the earth as a mother body, we might feel the damage that we do to her as pain in our own bodies.

Although she is not intentionally speaking about the climate crisis, her work exemplifies this profoundly.

Speaking of her Dialogues & Analogies series, South African artist and curator Gordon Froud said she shows how animal forms are equal with humans, whether they are spirit animals or a symbol of our co-dependency as we co-exist on Mother Earth.

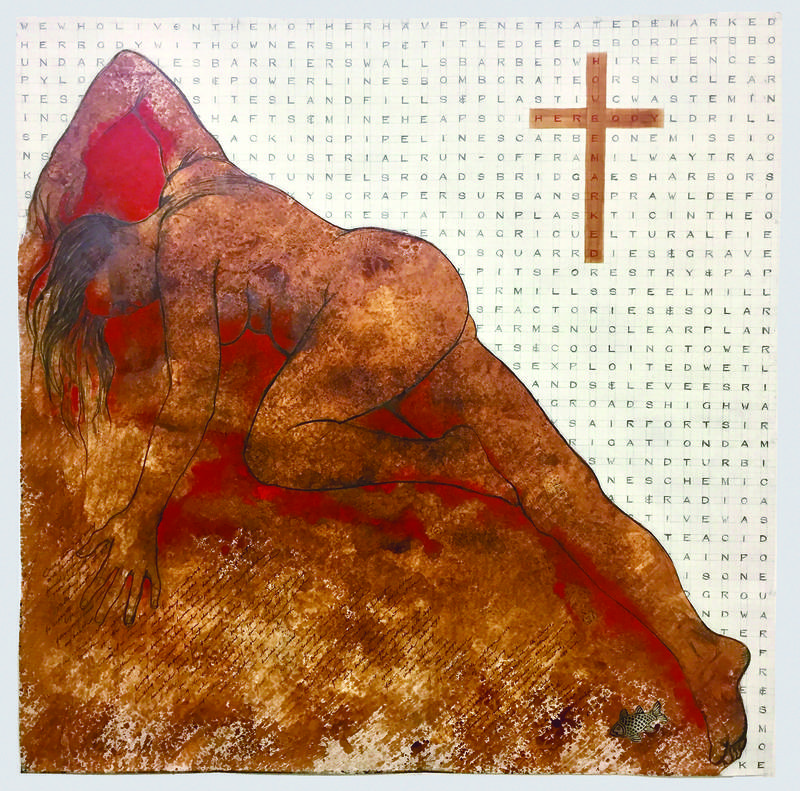

Majak Bredell’s work that is part of her exhibition Interconnections.

Majak Bredell’s work that is part of her exhibition Interconnections.

“What is particularly powerful about this body of work is that it is experienced or felt, rather than explained.

“Majak does not wield a stick of punishment or warning but suggests that we need to take better care of our earth mother, our planet, the animals, plants, each other and even the seemingly lifeless inanimate forms like rocks, mountains and landscapes,” he said.

“I suspect that she may suggest that they appear inanimate or lifeless but are in fact perhaps living and moving more slowly, and on a different vibrational level to us, and that we should acknowledge this.”

This collection contains 83 pieces and Bredell said it took her seven years of hard and consistent work in her studio in Limpopo to bring it to fruition.

One piece stands out for her — How Her Body Be Marked.

In the work, in a grid above the figure that represents the Earth, she lists the ways in which we have damaged the planet: “Our Human Deeds … We who live on the Mother have penetrated & marked her body with ownership and title deeds, borders, boundaries, barrier walls, barbed wire fences, pylons & powerlines, bomb craters, nuclear test sites, landfills & plastic waste, mining shafts & mineheaps, oil drills, fracking, pipelines, carbon emissions, industrial run-off, railway tracks, tunnels, roads, bridges, harbours, skyscrapers, urban sprawl, deforestation, toxic emissions & plastic in the ocean, agricultural fields & grazing tracts, quarries & gravel pits, forestry & papermills, steel mills, wetland & levees, ring roads, highways, airports, irrigation dams, wind turbines, chemical & radioactive waste, acid rain, poisoned oceans & groundwater fire & smoke,” it says.

Below the figure, she scripted earth’s dark, primitive and mysterious voice: “Once when my body was being formed from gases and rock, I was not yet stable enough to support life from my bones and my breath. The oceans would in time demark the outlines of the continents and allow the journey of tiny creatures from the deep watery depths onto the shore where they started breathing air.

“That was long before you, humankind, walked upright along inland lakes and ocean shores. Long before most of you abandoned gathering and hunting and began to plant seeds in my flesh to harvest for your daily bread.

“In all this, I was there, your mother, the body on which you lived while you became industrious using the rocks of my bones to build your temples and your palaces and your cities, and claimed my earth as property to be divided and fenced and walled as you waged wars over the boundaries you drew…”

Bredell considers herself iconoclastic — someone who challenges the norm and the traditional ways and suggests open and freer ways of thinking about the world.

Upending and questioning the patriarchy is also a major theme in many of her works.

The artist said that this interest in challenging the male system of dominance stems from her Calvinist upbringing and the subsequent opening of her mind during the 22 years she has spent living in New York.

She says the patriarchal writers of Genesis expunged the female from creation. She is not even part of the created world and, growing up in the Dutch Reformed Church, “Men were like little gods on earth and what were women?”

She uses figures tumbling or upside down to convey a re-thinking of hierarchy.

“We’ve been taught to look to the sky,” she said. “God is somewhere up there in heaven. But the sacred is right down here and it’s what sustains our lives on earth.”

Seasoned artist and writer Annali Dempsey said of Bredell: “When I look at Majak’s work, I think of the archaeological layers of civilisation excavated in places like Bath in England or Toledo in Spain where Moors, Jews, Christians and Romans created layers of reality according to religion, state and legislature.

“But it is still above the real earth — these compacted levels of history.

“And we tend to dance over these layers and levels with dazzling smiles and digital cameras, capturing what we perceive as the manifestation of what it means to live on this planet.

“What we do not see is the bones of the ancestors, the destruction and pain embedded in each of these layers that separate us over the ages from the earth mother.”

This is something we should all be thinking about. And driving to White River to see.

Bredell’s exhibition Interconnections, on at the White River Gallery, closes on 2 June.