Unsafe: Shannon Mowday (in the centre on the sax above) highlights that women have to fight for their space in the jazz sector. Photos: Supplied

Fifteen years ago, jazz performer, multi-instrumentalist, director, composer and arranger Shannon Mowday left South Africa.

She had already established her music career, having performed locally and internationally with a number of top performers.

Mowday was a recipient of the prestigious Standard Bank Young Artist Award for Jazz in 2007, alongside a number of other accolades. She had worked tirelessly to make her mark in the local jazz scene.

But, in 2009, she relocated to Norway, where she works as a performer, director and educator.

From there, Mowday still fights for women to have an equal opportunity to perform in the South African jazz industry, which is notorious for being deeply patriarchal and even unsafe for women performers.

This fear factor was among the main reasons she emigrated.

“I left because I couldn’t find where I could flourish with my story as a woman and because of the late-night gigs — having to travel by myself at night — I didn’t want to be in that environment anymore,” she told the Mail & Guardian.

“I was scared. I mean, it’s not about music. It’s about looking at South African statistics — one of the highest rates of abuse against women and children — and I’ve had so many of these experiences where, you know, it takes away from your life source.”

Mowday said the prevalent issue in South Africa jazz is that it has long been male-dominated, and as a result, women who are trying to go far are undermined and cut off from opportunities.

“Our blueprints in jazz were written by the men — the jazz men who were historically associated with drugs, alcohol and the unhealthy environments — and it was always men in the front line.

“Women always — even the ones who were really good — had to fight for their space.”

Mowday is sadly no exception to the rule. Far from it.

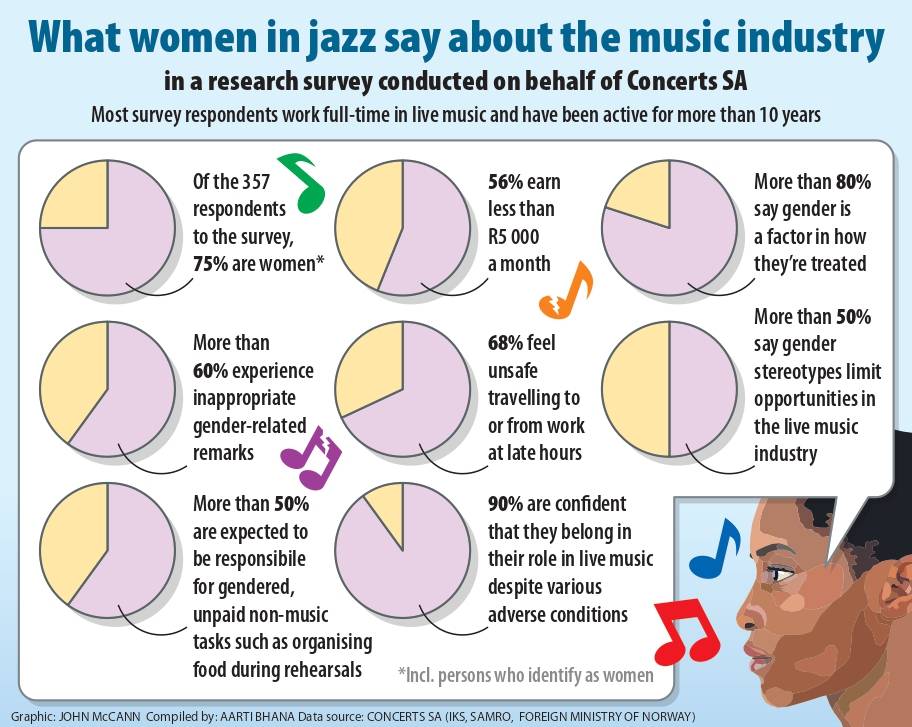

Concerts SA research conducted by IKS Cultural Consulting spoke to 357 women in live music late last year to gain insight into the lived experiences of women in the live music sector.

The M&G was given access to the report, which will be released soon to coincide with Women’s Month. It focused on female representation, how equitably women are treated and how safe they are and feel.

More than 70% of respondents said that they had observed gender discrimination in the sector and over 80% reported that their gender was a factor in how they are treated.

The outcomes on the issue of safety were disturbing.

Nearly a third (29%) of respondents had been pressured by work-related consequences to enter a sexual relationship; 15% were not granted the dignity of privacy backstage; 34.5% had experienced gender-based belittlement from employers or clients and nearly 40% had encountered it on social media.

Bum note: Jazz musicians Shannon Mowday (left) and Linda Tshabalala (right) say they have experienced unwanted sexual attention while working. Photos: Supplied

Bum note: Jazz musicians Shannon Mowday (left) and Linda Tshabalala (right) say they have experienced unwanted sexual attention while working. Photos: Supplied

More than a third of respondents saw nobody stepping in when gender-related harassment occurred.

Seven out 10 women — 73% — reported that their career progression was influenced by gender and 63% indicated that people in the sector behaved, directly and indirectly, in ways that were gender-discriminatory.

Mowday says women in South African jazz have experienced this for a long time.

“We are essentially living in what I would say are the male blueprints of how this history was created.

“So, certainly, for myself as a woman, I have always understood that the expression of what has been created in history was not what I aligned with,” she said.

Trying to go against the grain in the industry is deeply challenging and often translates into targeted hostility, danger and losing out on work opportunities.

“The disappointment I had was so many musicians behaving badly. So many. And then I can’t work with them again. And often when I’ve called out men in a band, I’m the one who has to leave.

“I think it’s sexual transgression but it’s also not being respected as a woman,” she added.

Linda Tshabalala, an award-winning jazz saxophonist who has been in the industry for more than 20 years, said, as a black artist, she’s not just up against white and black men but also white women.

“Everybody’s just up against you because I think people don’t expect much from us.

“They don’t really expect us to do amazing things or to do the best. So, when they come across some of us who are in the industry, it’s a shock and it sort of disappoints whatever assumptions that they had of us.”

Tshabalala said the hostility of the unequal power dynamics also plays out off stage.

“If they can’t beat you on stage, then they’re going to find another way to beat you. And that’s going to be a mental, physical, emotional issue.”

She told the M&G about two instances where she was sexually harassed by colleagues when she was still a student.

“At different times, different years, I was grabbed by different males trying to forcefully kiss me.

“I remember the first time it happened — I just shook it off and I didn’t know what to do. When I thought about it, and thought about telling my family, I was like, ‘Oh, my family is going to say leave the school right now and report the case’ and it’s going to be a huge thing. I kept quiet about it.”

Siya Charles also highlights that women have to fight for their space in the jazz sector. Photo: Supplied

Siya Charles also highlights that women have to fight for their space in the jazz sector. Photo: Supplied

But it did not stop there.

“After it happened the second time, I was like, no, this is becoming a habit. So then I reported the perpetrator to the family, and I reported him to [the late band leader] Dr Johnny Mekoa, and it was dealt with very swiftly.”

Mekoa is the late founder and director of the Music Academy of Gauteng.

Tshabalala said women in the industry are frequently subjected to sexual harassment by their male counterparts but they don’t do anything about it out of fear of losing work opportunities or having a reputation as a troublemaker who people won’t want to work with.

“I have noticed that we don’t openly speak about it, because we are afraid of losing out on gigs, because they will be labelled as troublesome. If I start speaking out about this more publicly then they would be like, ‘Oh no, we can’t associate ourselves with this brand.’”

Jazz journalist and writer Gwen Ansell has documented this issue in a number of titles including in her book Soweto Blues: Jazz, Popular Music, and Politics in South Africa, while Ceri Moelwyn-Hughes wrote about it extensively in their thesis on Women, Gender and Identity in Popular Music-Making in Gauteng, 1994 — 2012.

Ansell said harmful patriarchal practices existed in the industry and found their expression in myriad ways, from micro-aggressions to threats to women’s safety.

She told the M&G about instances where women didn’t have private changing rooms and where the dominance of the male gaze forced them to behave and look a certain way.

In addition to that, women are expected to work within certain music roles — such as being vocalists — even if they are exceptional instrumentalists.

The limitations imposed on women often force them out of the industry. However, Ansell emphasised that while it is prevalent in jazz, it is a common story in most sectors of the music industry.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

“The music industry is sexist because South African society is sexist. But, in fact, if you look at the international research, not just South Africa — the world is patriarchal and therefore the music industry is patriarchal,” Ansell says.

“I don’t think there’s anything special about either jazz or music and, particularly, I do think it’s expressed in specific ways.”

Respected composer and scholar Clare Loveday, across her long career, has also been privy to the abuse and discrimination that women are subjected to but do not speak about openly. She has been using her position to advocate for women’s inclusivity and safety in the music industry — not just in jazz but across different genres.

Loveday said she had heard of cases where women were abused and raped by members in their own band or orchestra and cases where women were asked for sexual favours in exchange for their safety.

“People talk a lot about the sort of pressure for sexual favours, which is quite strong,” she says.

“Also, the thing of, ‘If you sleep with me, I’ll protect you from the other men in the band. So, it’s either be harassed by them or sleep with me — so what are you going to do?’”

Loveday said women are often vulnerable in teaching rooms, during one-on-one sessions, behind closed doors. The difficulty of working in a space where there are known sexual predators further compromises the safety of women who are simply trying to do their job.

Siya Charles, a jazz trombonist and composer, has also been subjected to groping and harassment while working. She knows of several other women who have felt unsafe in the same way.

“A lot of times women, when we are in experiences where we feel trapped, we have a freeze response. It’s so unfortunate, because you want to stand up for yourself. But like, when [a] guy said that he wanted to fuck me … I just froze.

“I had to kind of change my approach and become a bit harder, which is not ideal, but it makes it easier for you to navigate in the space if you present yourself as someone not to be messed around with.”

After having worked internationally, Charles said when she is in South Africa, she feels less safe.

“I will be honest with you, when I came back home, I already felt the shift. I wasn’t even five minutes in, I was sitting during dinner at the artists’ table, and I was like, okay, I don’t feel safe anymore …”

This is scaled up further when some perpetrators get away with it and continue to work in the industry, often shielded by other men.

“The sad part is that a lot of perpetrators get defended by the jazz community.

“Women aren’t always believed, which is really sad — and then the guys are still working,” Charles said.

It’s not just an issue in the work environment but also in academic institutions.

Amanda Tiffin, head of jazz studies at the University of Cape Town, said she had received complaints from students about discrimination and inappropriate sexual behaviour.

On a personal level, she has encountered times when she was discriminated against and when her authority was questioned.

“I have experienced some discrimination and sort-of targeting because now I’m in a slight position of authority being the head of jazz … and projects that I lead do get targeted a bit by certain individuals who don’t particularly feel comfortable with women in positions of power and are threatened by that.”

Tiffin’s views and experiences at the institution confirm that there are cabals in the industry who actively, if not knowingly, work against women.

“A lot of people who are supposedly gatekeepers in terms of work opportunities, festival opportunities, booking agents, they’re most often men,” she says, “so they do have a lot of sway and so you’ll find that pre the #MeToo movement, you wouldn’t find a lot of female-led groups.”

She said, albeit slowly, conditions were getting better for women. They have become more vocal about the injustices they face.

Men who are accused of inappropriate behaviour are dealt with more seriously in recent times, especially where they are likely to continue interacting with the individuals against whom they have discriminated.

“Somebody has been intimidated and bullied while you’re still in the building. It’s not ideal. It can be quite traumatising for the individual that’s complaining because the nature of music is so interpersonally close; you have one-on-one lessons, you have small classes, you know, everybody knows everybody in the department it’s very tricky.”

Tiffin co-founded The Lady Day Big Band, which is a music collective that gives women a safe space to talk, create music, make mistakes and learn from them without the intimidation of “elder men” who seek to break women’s spirits.

More is needed, however, to ensure that women are able to hone their skills and work safely and comfortably in their respective spaces.

The Concerts SA research, which was funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the South African Music Rights Organisation, recommended that artistic work in live music is recognised in legislation — that includes labour laws on sexual harassment in the workplace, regulated payments and working conditions.

It should also apply quotas to ensure gender representation and support for a diversity of roles in music work and projects, among other things.

Out in the field, Tshabalala said, women should support each other when incidents of sexual harassment happen. They should feel more empowered to speak out, so that they can, as a collective, deal with the perpetrators and bullies who make it difficult to work.

Charles added that the most important thing is “female musicians are musicians” and they should be treated with equal respect, given fair opportunities and allowed to take up space without intimidation and fear.