More than history: A scene from Katanga, January 17, which tells the story of Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. (Oupa Bopape)

The play Katanga, January 17, at Johannesburg’s Market Theatre, is not just a recounting of history — it’s an exploration of love, loss, fear and the enduring consequences of a dream that was never meant to die.

Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, is often remembered as a symbol, a martyr for African unity.

But in this play, he becomes more than that — he becomes a father, a husband and a man, betrayed not just by political forces, but by the very people he fought to free.

Lumumba’s name has become synonymous with the struggle for independence in the Congo. He was a leader, a visionary and a martyr. But beyond the speeches and the iconic images lies a man who was stripped of his dignity, humiliated and executed, his body dissolved in acid as if to erase him from history.

Yet his memory endures, not only in the Congo but across the continent, where many still dream of the Africa he envisioned.

In the play, Lumumba’s humanity is brought to the fore. We see him not as a distant historical figure, but as a human being with flaws and vulnerabilities, who faced unimaginable terror in his final moments.

For the actors, the challenge is more than just learning lines. It’s about stepping into the shoes of men and women whose lives were shaped by violence, fear and betrayal.

Nji Alain, who plays Lumumba’s executioner, speaks with chilling clarity about his character’s motives.

“His executioner doesn’t hate Lumumba; he despises what Lumumba represents — the audacity to believe in a future he himself can’t touch,” he tells the Mail & Guardian after a performance.

“The executioner is trapped, driven by fear for his own life, forced to kill or be killed.

“It’s a tragic reflection of how fear can destroy hope, how survival can turn men into monsters.”

What is most striking about the performances is the emotional toll it takes on the actors themselves. The psychic cost of bringing these characters to life is evident in every performance.

Charly Azade, the Congolese actor who was originally cast to play Lumumba, speaks with quiet intensity about the weight of the role.

“It’s not just acting,” Azade admits. “It’s personal. Lumumba’s story is my story. The Congo’s story is my story.”

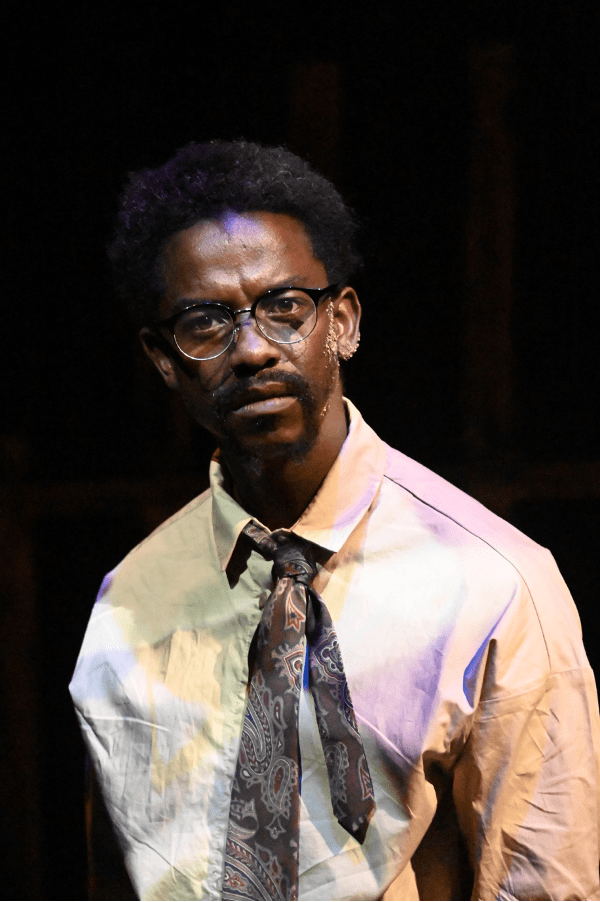

Thabo Malema plays Lumumba in the production, on at the Market Theatre in Joburg. (Oupa Bopape)

Thabo Malema plays Lumumba in the production, on at the Market Theatre in Joburg. (Oupa Bopape)

For the actor, the lines between himself and his character blurred, as he carried the pain of his homeland with him long after the curtain fell.

“I wake up with it,” he says, his voice barely above a whisper. “I go to sleep with it.“This isn’t just a role — it’s a part of me,” he says.

Azade was so deeply affected by playing the role that he had to pull out of the production.

His place in the cast was taken by Safta and Naledi award-winning actor Thabo Malema.

And that’s what makes this play so heart-wrenching — these aren’t just actors on a stage, and this isn’t just a history lesson.

This is real. It’s real for the Congolese actor who carries Lumumba’s story in his bones. It’s real for the South African performers who understand only too well the legacy of violence and division on their own soil.

It’s also real for the audience, who can’t help but feel the weight of Lumumba’s sacrifice and the brutality of his execution.

The cast, a pan-African ensemble of South African and Congolese actors, brings a raw, emotional intensity to the stage.

South African talents Billy Langa and Khutjo Green join Alain in weaving a narrative that is as much about the future as it is about the past.

The play’s director Khutjo Green, along with co-writers Lesego Rampolokeng and Bobby Rodwell, has crafted a narrative that seamlessly blends personal testimony with poetic storytelling.

The languages of the Congo —French, Kiswahili, Lingala — are woven into the dialogue, adding depth and authenticity to the performance. The actors move between languages with ease, creating a world that feels both intimate and universal.

Even for those unfamiliar with these languages, the emotions are unmistakable. The pain, the anger, the hope — it all transcends words.

As the final scenes unfold, the weight of the story settles over the audience like a heavy blanket.

But even as the lights dim, there is a sense that Lumumba’s dream is not dead. His vision of a united Africa, free from the shackles of colonialism and exploitation, still flickers, carried forward by those who refuse to give up on it.

The stage grows quiet, and Lumumba’s voice echoes. It’s a call to remember him — not as a symbol but as a man who dared to dream.

The actors bow, and the audience sits in silence, wrestling with the weight of what they’ve just seen.

Lumumba is gone.