Netflix's strategy has been to offer a blend of local and global entertainment

Netflix has come a long way from a DVD-rental-by-mail service to a global streaming giant boasting 269.2 million paid memberships in more than 190 countries, including South Africa.

“The journey was bringing Hollywood films and series to international audiences through new ways of distribution,” Netflix’s Larry Tanz tells me during our interview at a swanky hotel in Sandton.

“By looking at what else audiences wanted, local storytelling and audiences seeing themselves on screen became our mission. That was the leap of faith we took when we decided to commission our own films and series globally.”

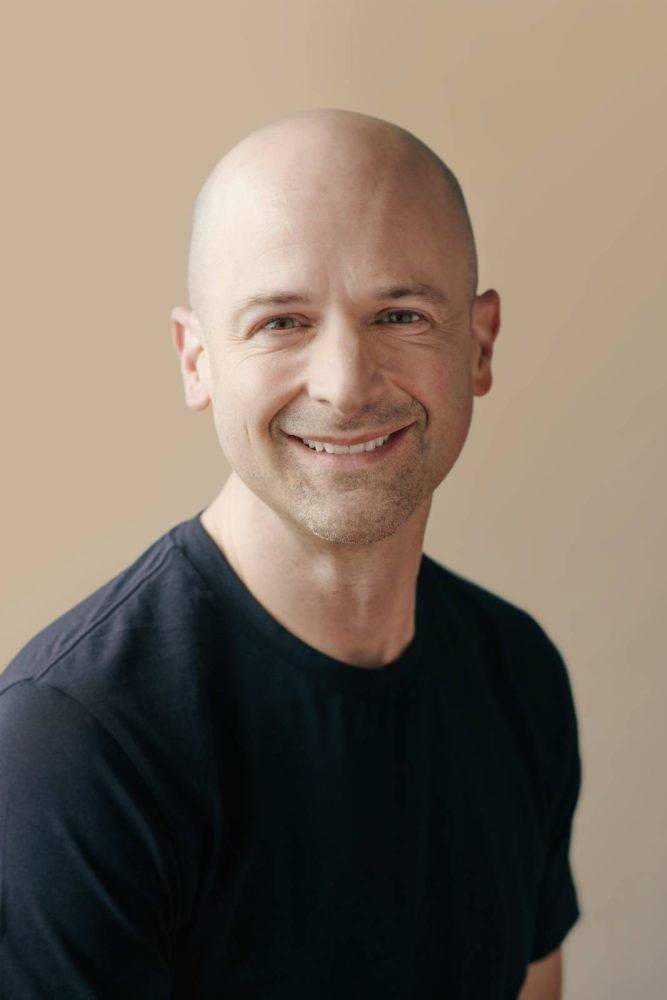

Tanz — coincidentally wearing similar casual grey pants to mine — is Netflix’s vice-president of content for Europe, Middle East and Africa. Seated next to him is a tall man in blue jeans and formal shirt — Ben Amadasun, director of content for Middle East and Africa.

After firm handshakes and introductions, the room is immediately filled with laughter and reflections on Netflix’s journey in Africa.

The two executives are here to engage with stakeholders, including talent, producers and media.

As they entered the conference room, it started raining, with a cooling breeze to end the persistent heatwave. It hasn’t been all sunshine and rainbows for this pair, though.

As rain represents blessings in most African cultures, I ask them about the successes — and challenges — of the African market since Netflix’s expansion to our shores in 2016.

Regarding the South African market particularly, Netflix’s strategy was to bring a blend of local and global entertainment.

“We know South Africans love their own stories and that, along with a really robust offering of films and series from all over the world … brings this incredible value, variety and quality that our members can stream in a taxi in Johannesburg or watch on their beautiful big-screen TV in their living room,” Tanz says.

The decades of management experience and passion between the two is evident in how they complement each other’s responses during the interview.

I ask them how they got the formula correct with record-breaking original shows such as Blood & Water and the How to Ruin Christmas franchise, among others.

“That’s the killer question!” Tanz says, chuckling.

Screentime: Larry Tanz (above left), Netflix’s vice-president of content for Europe, Middle East and Africa and Ben Amadasun (right), director of content for Middle East and Africa. Photos: Victoria Ushkanova, Mighty Fine Productions and Donwilson Odhiambo/Getty Images

Screentime: Larry Tanz (above left), Netflix’s vice-president of content for Europe, Middle East and Africa and Ben Amadasun (right), director of content for Middle East and Africa. Photos: Victoria Ushkanova, Mighty Fine Productions and Donwilson Odhiambo/Getty Images

Internal management from the African regions, historical data and having great local productions has proved to be a winning strategy for African markets, they say.

However, Tanz argues that data alone is not enough.

“The data is great for looking backwards but it doesn’t help in a creative business to clearly inform what stories we should make moving forward,” he says.

“In a creative business, if you try to repeat what you did before, you are probably not going to be successful, so it’s a constant reinvention.”

Amadasun echoes Tanz’s point that Netflix is a learning organisation. Organisational learning — a concept found in many business textbooks — contends that companies should be open to acquiring new skills to modify their internal processes to deliver innovative products and services.

By applying this approach, and adapting to changing markets, Netflix is constantly positioning itself as a flexible corporation, they say. Since expansion to the mother continent, it has had to learn about the different languages, cultures and aspirations of its audiences, though.

Amadasun weighs in to state that understanding local culture is an important strategic consideration.

“We are always trying to understand the landscape, languages, traditions and the real culture of people,” he says.

“That is why we have internal executives from the African continent who want to see themselves on screen. We have also been working with the local creative storytellers in the country to really get the stories that people love.”

Like other countries on the continent, South Africa has many different languages that need to be considered to offer a broad representation of stories.

“We have been intentional to make sure that productions are happening all over the country,” says Amadasun and cites the likes of Johannesburg-based Burnt Onion and Cape Town’s Gambit, along with Durban-based African Lotus and Stained Glass, as producer partners who have given that all-important authenticity to South African storytelling.

“We learn as we go along. As we learn, we try to serve our members even more,” he says.

“Why we are a unique company is how well we focus on that local market in the way the stories appeal to our members in that country. Not many companies are able to do that, not only in Africa, but across the whole world.”

Netflix’s appetite to learn is indeed miles ahead of global streamers Amazon Prime, who recently pulled out of African markets. This will hopefully give Netflix — and competitor MultiChoice’s Showmax — more opportunity to invest heavily in local talent and stories.

It is such growing competition and market understanding that has seen Netflix lose subscribers globally in recent years.

However, through innovation and more pointed local content, the global streamer has maintained its competitive advantage.

What impact, socially and economically, does Netflix have on African markets like South Africa though?

Between 2021 and this year, Netflix has invested about R4 billion in content and local creative ecosystems in South Africa, Nigeria and Kenya combined. It has supported the creation of more than 12 000 jobs, generated R5 billion towards GDP and funded economic activity that has generated over R786 million in tax revenue since 2016.

As the pair shares these notable numbers, there is light thunder in the background.

Tanz and Amadasun argue that such investment ripples out to have a broader impact than just on filmmakers but takes in other service providers such as production-equipment suppliers, drivers and stylists.

Tanz adds they have noticed the government’s economic, reconstruction and recovery plan identifies tourism as a huge economic driver.

“Millions of people who had never seen a South African story five years ago, now have seen a few,” Tanz says.

“We have also demonstrated with some research that people who watch a South African film or series are significantly more interested in the food, culture and travelling — thus inspired to visit South Africa.”

Tanz also spoke about the impact of the Wits Digital Equity Grant. He shared about one film student who, during her graduation ceremony, said she was helped by Netflix’s funding initiative at a time when she struggled to pay for her tuition.

“It’s a real story that she told. She gave me goosebumps. The most gratifying thing for us is hearing these graduates coming through and working on Netflix projects.

“Ultimately, it is about making a living in the industry.”

Besides the growth in countries such as Nigeria and Kenya, the two executives affirm that South Africa is their focus at the moment.

“We are going broader and deeper. We are broadening our offerings of non-fiction, unscripted format and doccie-soapies because we know our audiences love watching those,” Tanz holds.

“So, it is not a radical shift, it’s about getting better and broader. We are meeting our audience where they are, with a better understanding of their preferences.”

In an African environment, with a high level of digital inequality, high data costs and cultural differences, many global companies have failed.

Netflix’s localisation strategy has, however, proved to be a winning recipe for continuing its mission to entertain the world.

Its efforts stretch beyond entertainment for subscribers and work opportunities for local filmmakers to a much-needed social and economic impact.

From scholarship opportunities to master classes, internship opportunities and partnerships with local industry stakeholders, Netflix is committed to finding opportunities to grow the talent in the local production ecosystem.

Like a child learning how to talk, act and interpret their surroundings, in its eighth year in the African market, Netflix is still fervently learning, taking creative risks and aiming to impact one household at a time.