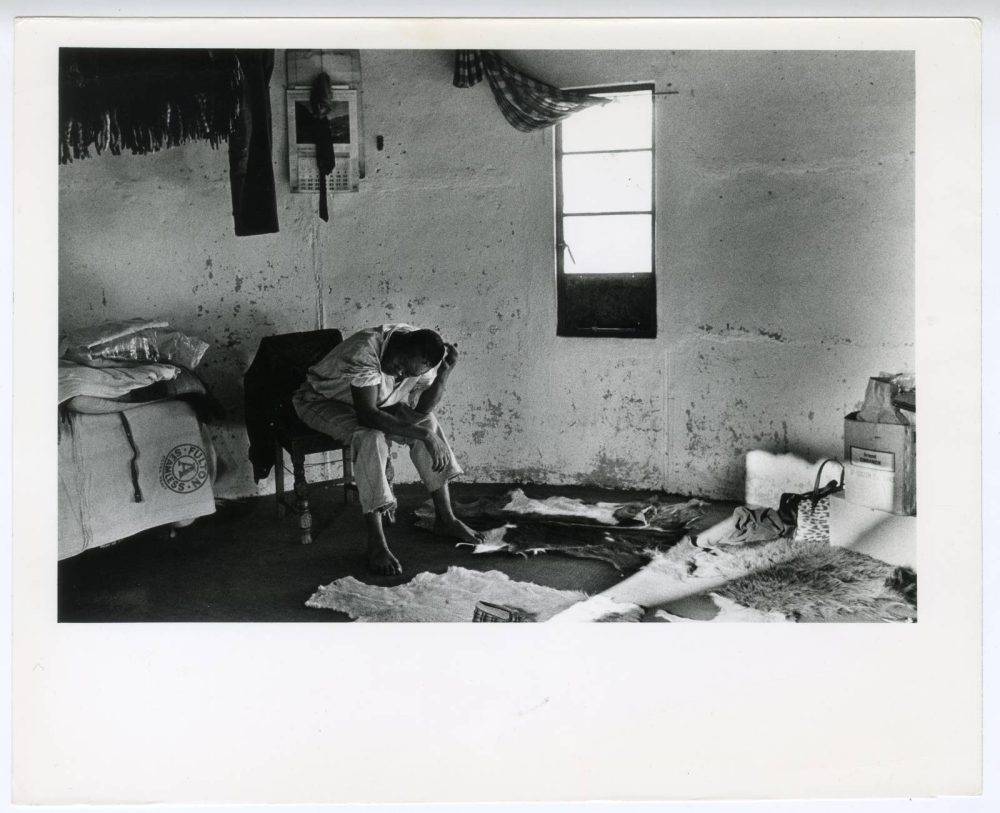

Previously unseen: In 1964 Cole travelled to Frenchdale, a remote settlement in the Northern Cape, to document the lives of these internally displaced political exiles

The story of Pretoria-born photographer Ernest Cole, who died in exile 35 years ago with one book of photographs and little else to his name, is still being recovered. The methods of this recovery are diverse.

Goodman Gallery in Cape Town is presenting an exhibition of vintage prints linked to Cole’s classic photobook House of Bondage throughout the month of February.

Haitian filmmaker Raoul Peck’s latest documentary, Ernest Cole: Lost and Found, which is slated for local release in March, retells Cole’s extraordinary story through the incendiary photos he made of black life in 1960s apartheid South Africa.

For decades, Cole’s identity was synonymous with the 183 photos included in House of Bondage but the 2017 discovery of a huge cache of his negatives in a Swedish bank, and slow retrieval of his prints from various European archives, has enabled a more expansive view of his legacy to take shape.

Both the Goodman Gallery exhibition and Peck’s film provide a broader insight into Cole. Unavoidably, it implicates South Africa’s haunted past.

In 1959, a year after joining Drum magazine in Johannesburg, Cole was gifted Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photobook The Decisive Moment (1952).

“I knew then what I must do,” wrote Cole in 1968. “I would do a book of photographs to show the world what the white South African had done to the black.”

This decision changed the course of Cole’s briefly luminous but ultimately tragic life.

The early days of May 1968 were especially consequential for Cole. On 6 May, Cole’s passport — the document that had enabled him to leave South Africa two years earlier, ostensibly on a religious pilgrimage to France, but actually to work on his incendiary book of photos in New York — expired.

He scheduled an appointment to renew his passport at the South African Consulate in New York. He needed a valid document to maintain his American residential papers, as well as to travel abroad in support of his well-received new book.

First published in New York in 1967 and London in early 1968, the photos in House of Bondage are mostly illustrative of black life in Johannesburg and Pretoria. Collectively, they operate to visualise what Cole in the first chapter describes as the “extraordinary experience to live as though life were a punishment for being black”.

Previously unseen: In 1964 Cole travelled to Frenchdale, a remote settlement in the Northern Cape, to document the lives of these internally displaced political exiles

Previously unseen: In 1964 Cole travelled to Frenchdale, a remote settlement in the Northern Cape, to document the lives of these internally displaced political exiles

Individually, they present things like crowded train commutes, brutal work circumstances, predatory credit systems, atomised family relations, impoverished schools, youth delinquency, police harassment, bullying municipal signage and the consolations of spirituality and family.

Many of these conditions are described in the Goodman exhibition, which concludes a three-part international showcase of Cole’s vintage prints held in London and Paris.

The Cape Town selection, which is presented in collaboration with the Magnum Gallery, Paris, and the Ernest Cole Family Trust, covers nine of the book’s 14 organising rubrics. There are photos about education, hospital care, urban poverty and political banishment.

Twenty-seven of the 35 vintage prints do not appear in the original hardcover edition of House of Bondage. Many of the prints, however, directly relate, in time and geography, to frames appearing in the book’s 14 illustrated chapters.

The photograph of a bride being chauffeured in a rented American convertible offers a different angle on the same animated moment recorded on page 172, in a chapter about middle-class black life.

The destitute women hawking outside Denneboom railway station, near where Cole was born on the outskirts of Pretoria in 1940, is pictured in a more energetic pose on page 90.

The four passive youths gathered around an architectural pillar in Pretoria’s CBD are from the same gang of pickpockets that Cole describes at work outside the Eastern Silk Bazaar on page 135.

Other works in the exhibition are harder to locate, like some of the unseen prints from his exploration of religion and various photos of mine labourers being processed for work and at grim leisure. These were clearly jettisoned in the editing process. This happens.

Cole worked on his book project with concentrated focus from at least 1963, the year a motorbike accident landed him in Joburg’s Baragwanath Hospital for 26 days.

The experience suggested a new area of focus. The six young men, two with bandaged eyes, another with his arm in a sling, in one of the unseen prints on view are probably inmates of the hospital.

When, in 1968, apartheid censors encountered Cole’s book they exercised a powerful veto. It was included on a list of 21 “indecent, obscene and objectionable” books banned from importation to South Africa in the Government Gazette of 8 May 1968.

The government-appointed censorship board’s deliberations were always held in secret. A 2022 search I undertook at the National Archive in Cape Town, which holds the extant papers of the censorship board, yielded nothing.

Whatever the bureaucratic rationalisation for the banning, it is fair to say that the state was pissed off. Cole became the subject of a concerted backlash.

“I’ve been advised that my passport will not be renewed but that I could obtain an emergency travel certificate to permit my return to South Africa,” he explained in duplicate letters sent to Swedish and Norwegian state officials in November 1968.

“Following publication of my book, House of Bondage, I am afraid to return to South Africa for fear of arrest, imprisonment, or worse.”

Worse essentially happened. Cole became an involuntary exile. His career in New York and Stockholm briefly flared but the cruelty of banishment ultimately crushed him. He left photography and became a man without a fixed address.

“He was like somebody who was terribly exhausted, physically and mentally, somebody who was almost in a state of collapse,” recalled artist Peter Clarke of the time in 1976 he encountered Cole in New York.

Cole died in a New York hospital in February 1990, a few days after seeing Nelson Mandela walking out of prison on television.

“People don’t realise what exile is,” Peck recently told Canada’s POV Magazine during a media blitz promoting his new documentary.

“Every day, you are living somewhere else, but life continues where you left. You have news from your parents, your friends. People are being killed, being kidnapped, being abducted. That’s your daily life …

“People think that being in exile is something exotic. No, you are torn in the middle.”

Is this the past we want to remember?

“As failures go, attempting to recall the past is like trying to grasp the meaning of existence,” wrote the exiled poet Joseph Brodsky in a 1976 biographical essay. Denounced and imprisoned in his native Russia, his work also banned, Brodsky favoured an “elegiac” tone in his autobiographical writing but acknowledged “rage would be more appropriate”.

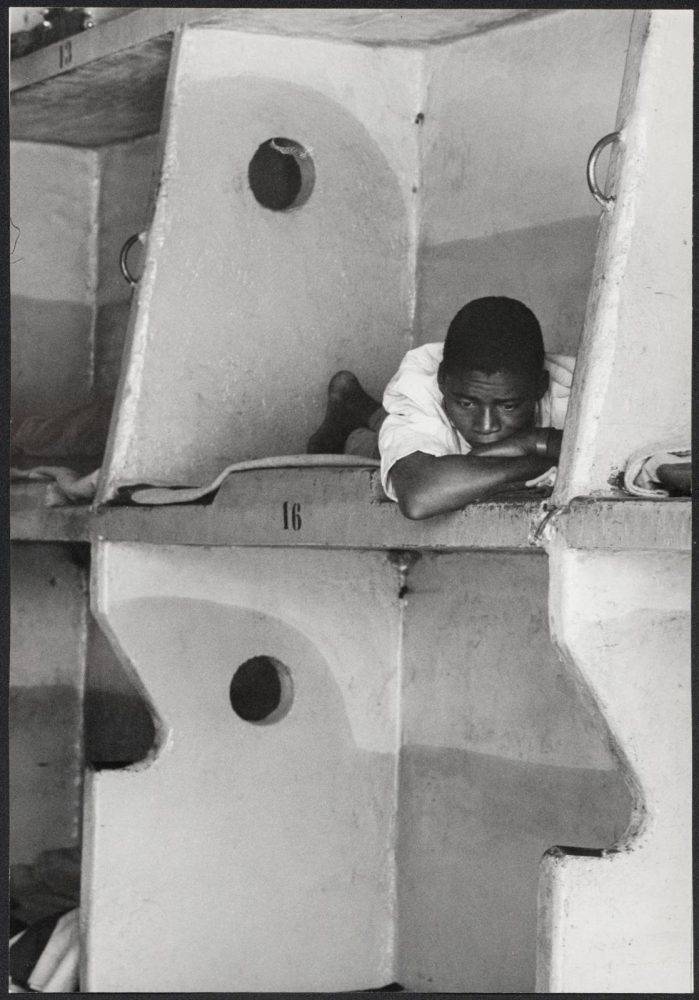

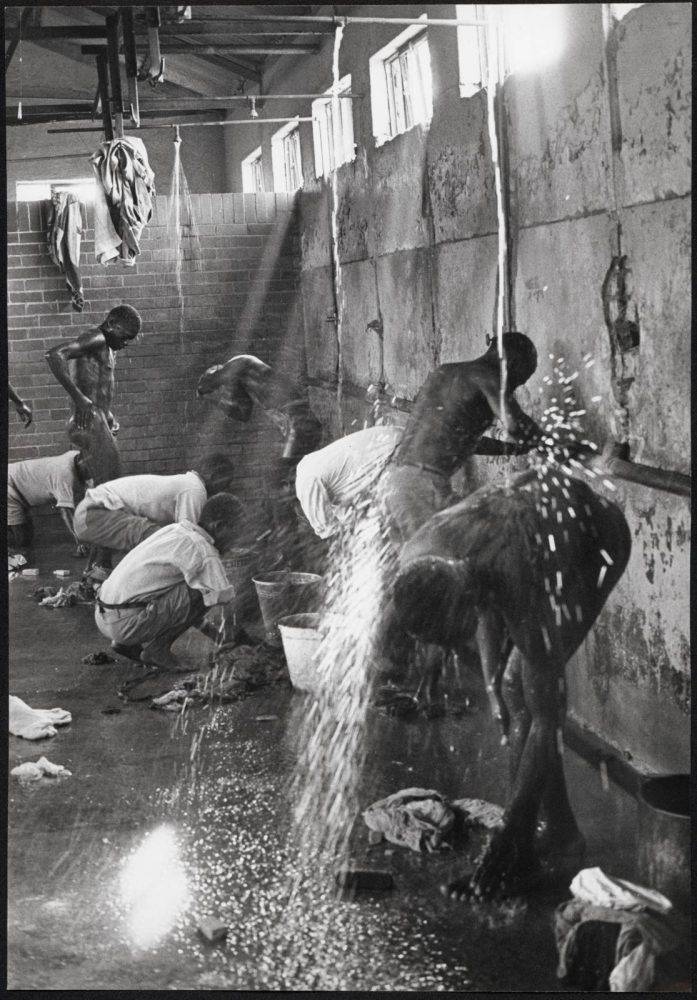

Grim evidence: Cole’s many photos of the mine industry from the early 1960s include these unseen works of the barracks-like compounds. All photos courtesy Goodman Gallery, Cole Family Trust and Magnum Gallery

Grim evidence: Cole’s many photos of the mine industry from the early 1960s include these unseen works of the barracks-like compounds. All photos courtesy Goodman Gallery, Cole Family Trust and Magnum Gallery

Recalling Cole’s courageous, but tragic, biography invites both rhetorical modes: elegy and indictment.

A lament because, despite his enormous talent, an uncommon gift for combining sociological clarity with stoic lyricism in his photography, Cole died destitute and unheralded in exile.

And rage, well, do I need to offer any more justifications for it? Cole was unable to escape his identity in a throttling white world, as much as he hoped and tried.

“In my observation of the Black man’s life in South Africa as presented in House of Bondage, my personal attitude was committed to exposing the evils of South Africa,” Cole wrote in a 1968 letter. “When I left home I thought I would focus my talents on other aspects of life, which I assumed would be more hopeful, and some joy to it.”

But these flickers of joy, which an updated 2022 edition of House of Bondage acknowledges, were not permitted to Cole in life.

“Recording the truth at whatever cost is one thing but finding one having to live a lifetime of being a chronicler of misery and injustice and callousness is another.” Cole tapped out. He disappeared, became invisible. He is still being rediscovered.