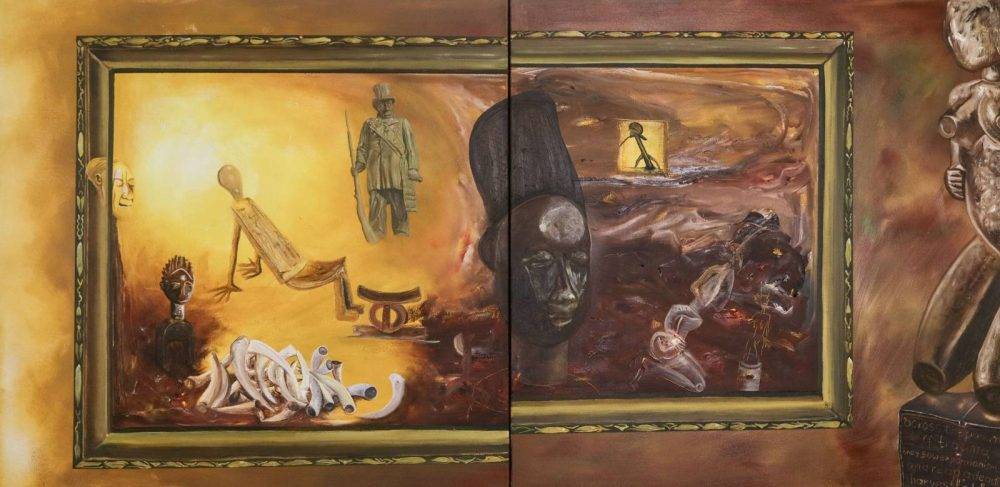

Confrontation, by Phoka Nyokong. (Photo supplied)

One of the most pathetic ironies of art history is that the best places in the world to see the oldest and most precious African artefacts are outside of Africa.

The theft of cultural heritage is a lingering wound of colonialism that continues to fester in the form of looted artefacts housed in European and American museums.

This is the reality at the forefront of South African artist Phoka Nyokong’s aptly-titled exhibition confrontation showing at Gallery Momo in Joburg.

Through a collection of stunning oil paintings, Nyokong interrogates the uneasy relationship between Africa and its past, particularly the violent dispossession of artefacts which are in foreign museums and private collections.

Speaking about the inspiration behind his work, Nyokong explains: “In 2020, I started working on a larger body of work titled Ethnology for Genocide: The History Paintings.

“This working title was a way for me to think through questions about cultural heritage, African heritage and African ownership of our own history,” he says.

confrontation is the fourth Phoka has shown under that working-title umbrella. Two of those were part of group exhibitions, and this is the second solo show focusing specifically on African cultural objects, sculptures and heritage.

Exploring this exhibition made me consider all the African artefacts held hostage in European museums.

Their violent history — looted during colonial conquests, stripped from sacred sites, stolen from homes — means their presence in institutions like the British Museum and the Ethnological Museum of Berlin is not neutral. They were never willingly given; they were taken. Their continued presence in European collections is not just a matter of history — it’s a matter of justice.

Study in Sepia (Mother and child at Communion). Photo supplied

Study in Sepia (Mother and child at Communion). Photo supplied

“There are two distinct areas of thought in this exhibition,” explains Nyokong. “The title itself confrontation carries a lot of meaning. In everyday language, confrontation is a distinctly human action or behaviour. It carries ideas of hostility, battle, engagement, even war.

“But, artistically, when I arrived at the idea of confrontation for this show, I started looking at references — what other artists, thinkers and creatives had done with the concept.

“Then, I came across the work of Okwui Enwezor, a Nigerian curator and a pioneer in the art world. He passed away in 2019 — may his soul rest in peace. By the time I had settled on the title confrontation, I was already more than halfway through the paintings. I was thinking about how to solidify the concept in writing and in thought.

“Then I found an interview where Enwezor talked about how we might frame and understand the contemporary moment of African art and artists, both on the continent and in the diaspora.

“He suggested that, collectively, though you can’t generalise too much, African artists and those from indigenous backgrounds in the Global South are engaged in a confrontation with empire.”

Nyokong’s reflections align with a growing global discourse on the return of African artefacts. The question of repatriation has gained momentum in recent years, with countries like Nigeria, Benin and Ethiopia demanding the return of their looted heritage.

But these demands are often met with resistance from European institutions, who hide behind bureaucratic excuses, vague promises or outright refusals.

France, under President Emmanuel Macron, made a grand gesture in 2017, announcing plans to return artefacts but only a handful have been returned.

The British Museum, which holds thousands of looted items, insists it cannot return them because of a law preventing deaccessioning from its collection. And Germany, while making some strides in returning Benin bronzes, still holds a staggering number of stolen African artefacts.

This theft of meaning is one of the deepest wounds of colonial looting. It’s not just that these objects are missing from their home countries — it’s that their entire purpose has been altered.

Sacred sculptures once used in ceremonies are aesthetic curiosities for foreign audiences. Royal regalia that symbolised sovereignty are reduced to artefacts of an “exotic” past.

Across the panorama of trauma, they sow expansion…and reap a deadly harvest. Photo supplied

Across the panorama of trauma, they sow expansion…and reap a deadly harvest. Photo supplied

The reluctance to return these artefacts is often couched in paternalistic rhetoric. European institutions claim African countries lack the resources to care for them. Some argue returning them would “erase history” or deny the world access to universal heritage. But these arguments crumble under scrutiny.

As French art historian Bénédicte Savoy argues in Africa’s Struggle for Its Art: History of a Postcolonial Defeat, the idea that African countries cannot care for their own cultural treasures is both racist and absurd.

“The claim that African nations lack the means to protect their own heritage is a colonial myth perpetuated to justify continued possession. The real issue is not conservation, but control — who has the right to tell the story of these objects, and whose history is being safeguarded.”

Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal and Ethiopia have museums equipped to house returned objects. Moreover, many of them were taken from sophisticated cultural and political institutions in the first place — institutions that were deliberately dismantled by colonial powers.

In Liberalism: A Counter-History, Italian historian Domenico Losurdo underscores the hypocrisy of Western liberalism when it comes to issues like restitution.

He argues while the West prides itself on ideals of democracy and justice, its actions — both historical and contemporary — betray an ongoing commitment to domination . The refusal to return stolen artefacts is a clear example of this contradiction

“The liberalism that proclaimed the rights of man in the abstract simultaneously denied them in practice, restricting them to a privileged minority while subjecting entire peoples to colonial plunder. The rhetoric of freedom functioned as a smokescreen for expropriation, enslavement, and the violent appropriation of cultural heritage.”

Despite foreign reluctance, the fight for restitution is gaining ground. Since 2021, dozens of Benin bronzes have been returned to Nigeria from British and American institutions, such as Jesus College, part of Cambridge university; The Horniman Museum and Gardens and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art Ethiopia has recovered sacred artefacts, including a Bible and an imperial shield plundered by British forces in 1868.

Activists and scholars across Africa and the diaspora are applying pressure on museums and governments to return looted objects.

In last year’s documentary Dahomey, French filmmaker Mati Diop blends facts and fiction to narrate the return to Benin of 26 royal artefacts of the Kingdom of Dahomey. They were taken to France during the colonial period and later put on display in Paris. This was the result of a repatriation campaign.

The film won the top prize at the 74th Berlin International Film Festival and was the Senegalese entry for the 97th Academy Awards where it was shortlisted in the documentary feature film” and international feature film categories.

Artists like Nyokong play a crucial role in this global fight for repatriation. Through his work, he is not just creating art, he is engaging in a conversation about history, memory and justice. His reflections on confronting empire highlight what is truly at stake in the restitution debate.

The idea that these objects are mere “museum pieces” is a distortion. They are part of living cultures. They belong in the places where they can continue to serve their intended purpose — whether that is in ritual, in education or in national memory.

Repatriation is not just about objects; it is about the people those objects were stolen from. It is about the communities that were robbed of their cultural heritage. It is about the continued power imbalances between Africa and the West.

Returning artefacts is one step — but it must be part of a broader reckoning with the legacies of colonialism.

The West cannot continue to profit from African art while denying Africans access to their own history. Justice would mean not returning stolen objects but also supporting African institutions, funding cultural preservation efforts and acknowledging the full extent of the harm caused by colonial looting.

Phoka Nyokong’s work reminds us history is not merely something to be studied — it is something that must be reckoned with. And until Africa’s stolen treasures are returned, the reckoning remains incomplete.