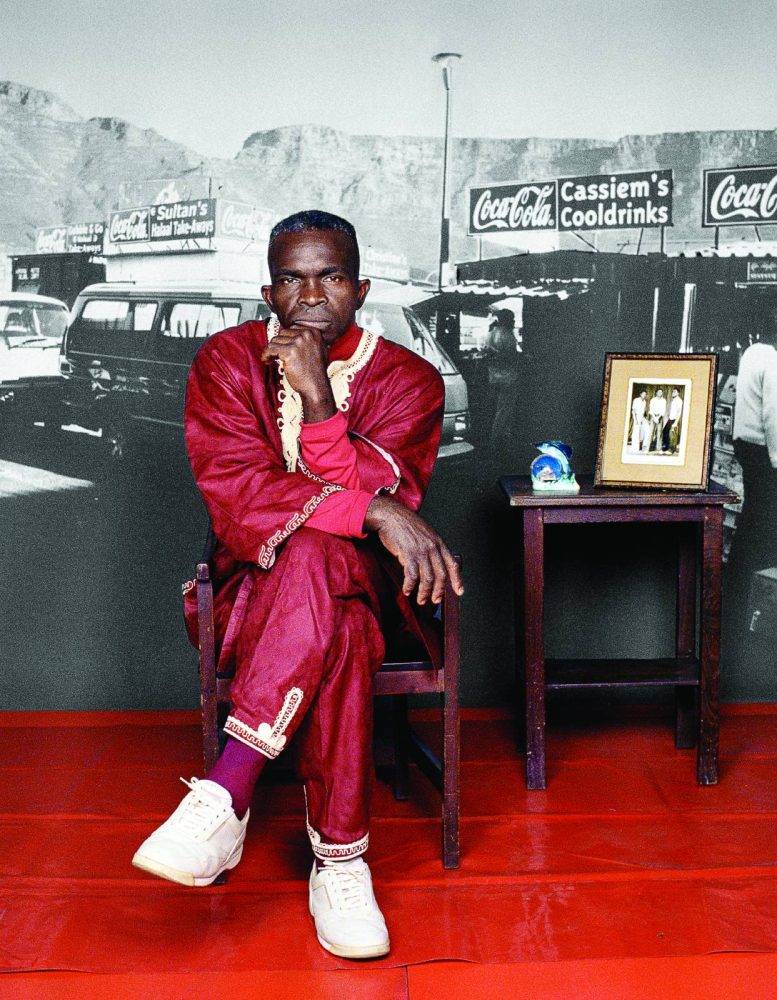

Sue Williamson’s work Better Lives Nelson Manuel, 2003.

Just after 1pm on a Friday, I follow Sue Williamson through the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town into a room that houses one section of her upcoming exhibition, titled Inside the Studio.

It is exactly what one might imagine — one wall is covered in a floor-to-ceiling wallpaper reproduction of the bookshelf in Williamson’s studio, while the other half serves as a kind of archive. She asks if she can label snow globes while we talk and I take the rare opportunity to observe her at work.

The 84-year-old artist and activist is preparing for her first retrospective, titled There’s something I must tell you after one of the works on the show, which is opening the next day. The gallery is still a flurry of activity.

As she works, carefully labelling globes collected from cities she has exhibited in, she talks me through what led to the retrospective.

“It’s been on my mind for a long time because I’ve got a lot of work,” she says. “And a lot of artists have all had retrospectives but it hadn’t happened for me.”

She shows me some of the snow globes she has collected. “The trashier, the better,” she says.

On the opposite wall, the gallery has installed a timeline that chronicles the significant historical events that Williamson has covered in her art — all the way from the 1600s to the present day.

Glass cases stand below this timeline, housing objects taken from Williamson’s studio, some of which inspired artworks on the show.

The exhibition spans Williamson’s entire career, and each room has a different theme, helping the works to form a continuous narrative.

“The piece that’s in the courtyard is actually in the collection of the national gallery and they’d never hung it before because of the difficulties of hanging it.

“When Andrew [Lamprecht] and I were working on that, he said, ‘It would be really nice if you had a retrospective here.’”

The artwork she is referring to, Messages from the Moat, hangs in the courtyard of the gallery. Suspended in a fishing net are 1 400 glass bottles, each inscribed with the name, birth place and the sale price of an enslaved person.

The people memorialised in this work include men, women and children who were shipped to Cape Town and traded from 1658 to 1700, in the early phase of Dutch colonialism.

Water pours from the middle of the artwork, giving it a sense of movement and presence in the space.

Considering the sheer volume of work that Williamson has produced, I consider the Iziko South African National Gallery the right place for this exhibition. The works have space to breathe and each is given due diligence.

Sue Williamson’s work All Our Mothers Caroline Motsoaledi, Soweto, 2012.

Sue Williamson’s work All Our Mothers Caroline Motsoaledi, Soweto, 2012.

Williamson agrees, saying, “The national gallery actually has eight of these works in their own collection, so it makes sense.”

I ask Williamson what she hopes young people can gain from an exhibition like this.

“Again, just some sense of what went on in this country. So many young people today don’t know.

“I heard even 10 years ago that schoolchildren didn’t know what a passbook was.”

As an art journalist, I experience her work as distinctly archival — even journalistic.

“I think it has that element. It is documentary in many ways,” Williamson says.

She takes me over to a print hanging on the wall of the studio room.

“I was paging through Farmer’s Weekly in a doctor’s office and I came across this headline: ‘Stop terrorists with sisal’.”

Sisal is a hardy plant native to southern Mexico with an appearance similar to that of an aloe. The stiff fibres taken from it are used to make rope, carpeting and paper.

The plant’s use as an anti-terrorism effort seemed inconceivable to Williamson at the time.

She continues, “It seemed extraordinary to me that border farmers should need to plant sisal to stop terrorists and these are the terrorists.” Williamson points to a silhouette of a mother and child.

“I’m very interested in posing these binaries — what is said, versus the reality of the situation.”

This binary, present in Williamson’s work, also interests me. Specifically, I am thinking of the work called Don’t let the sun catch you crying, a brand-new installation piece that forms part of the room titled The Story of District Six.

This room houses works that were made from 1981 to the present and they chronicle the destruction of District Six in Cape Town, an area which was once home to a vibrant and diverse community.

Sue Williamson’s work Better Lives Richard Belalufu, 2003

Sue Williamson’s work Better Lives Richard Belalufu, 2003

“That’s because I like continuing with things,” Williamson says. Many of the newer artworks in the exhibition were made as responses to earlier projects.

The title work of the retrospective, There’s something I must tell you, features six exchanges between women and their grandmothers.

Caroline Motsoaledi and Amina Cachalia, two of the grandmothers featured in the work, are also included in A Few South Africans, a photographic series which aims to honour women’s contribution to the struggle for freedom.

In the same way, Williamson returned to the story of District Six recently by creating an installation, using the same chairs she used decades earlier, generously provided by the Ebrahim family.

Williamson discusses her reservations about possible plans to rebuild District Six, none of which have come to fruition.

“I would like readers to feel that it’s time that people pressured the state to rebuild District Six. They’ve actually passed the plans — there are very good plans for it — but there have been many excuses,” she says.

“But it’s more than time to do something about District Six. So, I’m hoping this exhibition will again raise consciousness on it.”

In many ways, Williamson’s work serves as a stark reminder of the history of the South African people. Through her art, she chronicles the vast and diverse range of painful events that will forever form part of the South African collective consciousness.

I wonder how she deals with the intensity of it all.

“I’m trying not to ignore things that are there, without being too dramatic about it. Just being aware of things that are going on, that we have to acknowledge — we can’t just pretend it’s not happening. Redress has to take place.”

There’s something I must tell you is on at the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town until 24 September.