Omar Badsha And Dumile Feni At The Durban Art Gallery

Publisher’s note: This extract follows Omar Badsha — the award-winning South African artist, photographer and activist — as a young man living in Durban in the late 1960s, as he grapples with the oppressive weight of apartheid. Omar, deeply affected by the social and political upheaval, reflects on the loss of his mentor, Jeevan Desai, an anti-apartheid activist who was banned and later died under suspicious circumstances. Amid personal and political turmoil, Omar seeks solace in art, friendships and activism, trying to make sense of his role in a deeply divided society.

This passage is a lightly edited excerpt from Daniel Magaziner’s biography of Badsha, Available Light.

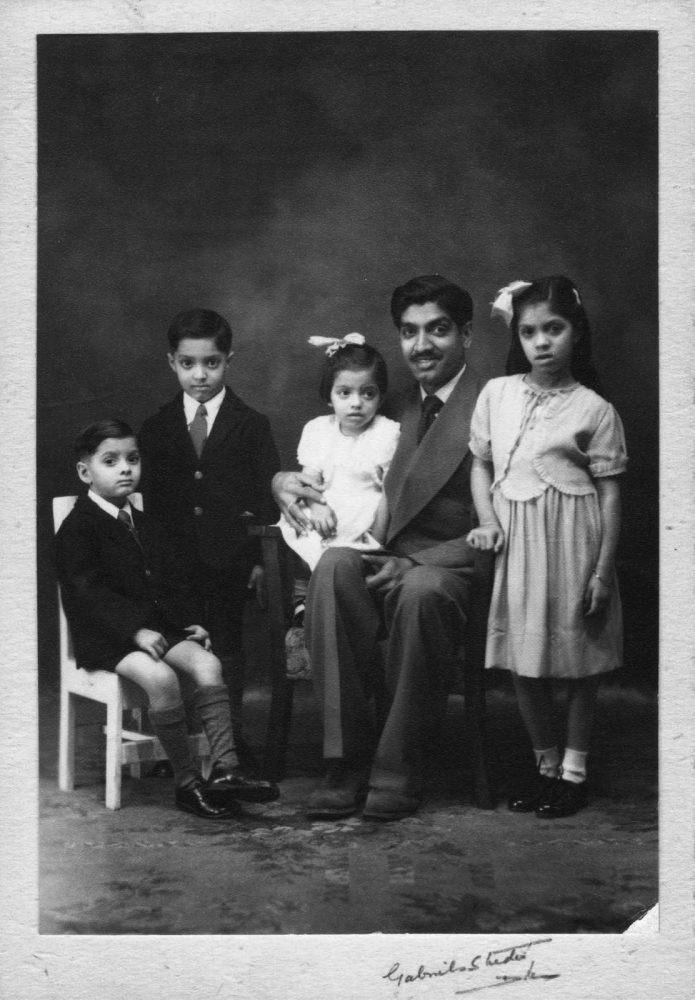

The house on Douglas Lane was on the lower slopes of a great hill, just across the railroad lines from Durban’s central business district. It had a small outbuilding in the backyard. It was stifling in the humidity and leaked a bit in the rain, although the green canopy of the Umdoni tree overhead provided some shelter from both. That back room, separate from the rest of the house, was where Omar stayed. He was the eldest son of a family that had lived for more than fifty years on South Africa’s southeastern coast, most of them on Douglas Lane.

In 1967, he spent most of his time in that back room, although the damp air left him with a recurrent flu. There he had books, pamphlets, newspapers, inks and pencils, with which he grappled daily in his ongoing quest to be an artist. He was angsty, tense, frustrated; he obtained a Lufthansa-branded weekly planner and used it as a diary, seeking to capture in its pages his yearning for a “change of atmosphere,” for himself, his family, and his country. He wrote and he drew and in between he walked around the neighbourhood.

It was impossible to separate his own situation from what he saw in the surrounding streets. His was a cosmopolitan part of Durban; although many of his neighbours were, like Omar, of Gujarati Muslim descent, there were also Hindus, Christians and even Jews nearby. During the daylight, the neighbourhood — known as Wills Road, for a nearby street — was bustling, lively, diverse. After dark, the white neighbourhoods higher up the hill were guarded by both the police and the government’s segregationist laws. These laws — known as apartheid — were increasingly penetrating the neighbourhood, the diversity of which offended the state’s mania for clear divisions between people.

Some neighbours were being compelled to move away from the city centre, to segregated townships on the fringes. […] Their houses were bulldozed in their wake. A planned freeway would rend the community in half. “There is a sadness that eats my district,” Omar reflected after returning from one outing. “Apartheid is like a cloth, slipped over the face of a man, choking us.” The threat of suffocation came closer still. Early in 1967, Omar’s father received a letter informing them they would have to vacate their home under […] the notorious Group Areas Act.

Ebrahim Badsha was sociable and extroverted; he was also quick to anger. He, too, had wanted to be an artist but was repeatedly frustrated by a lack of opportunity and social pressure to earn a living for his family. The letter was vague about timeline and particulars, but it carried terrible weight. The mood on Douglas Lane frequently soured. Omar and Ebrahim argued, repeatedly, vehemently. Omar turned twenty-two years old in June, under the shadow of expulsion.

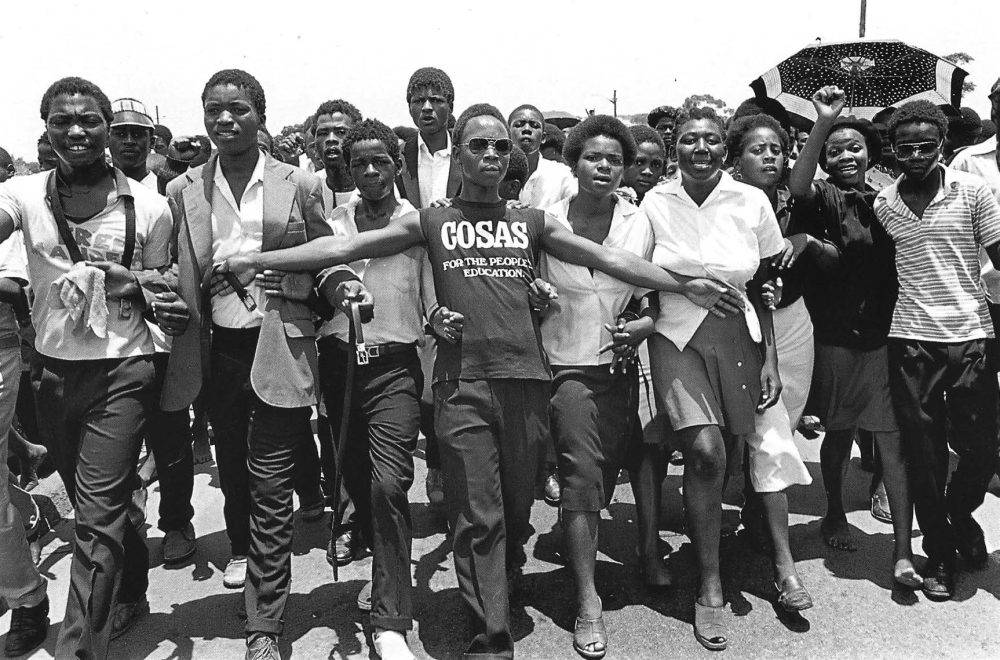

Nineteen sixty-seven’s slow-motion suffocation was in stark contrast to the beginning of the decade, when a broad-based movement to end racial discrimination had touched nearly every community and found widespread support within many of the country’s diverse communities — Omar’s included. Omar had been a student when activism reached a fever pitch in 1960; only 15, he had become involved in the Durban Students’ Union, a mostly Indian student group dedicated to replacing white minority rule with a representative, race-neutral, and economically equitable system.

In the DSU, he came under the sway of Jeevan Desai, one of the organisation’s leaders. Desai was a college student, from the same neighbourhood, connected to activists across the country. He was assured, impassioned, eloquent. He preached a politics that reasoned, since apartheid divided, the absolute, non-negotiable foundation of resistance to it ought to be unity of South Africa’s oppressed peoples. Organisations, in their constitution, their maintenance, and their practices, had to be everything the state was not: democratic, transparent, rule abiding, and open to all. Members of groups like the DSU or other organisations might know themselves or each other as “Africans” or “Indians”, “Christians”, “Jews”, or “Muslims”, “communists” or “nationalists”, even “whites”, but what really mattered was their shared commitment to their organization’s goals.

Non-racialists like Desai did not deny the salience of race; rather, they claimed that non-racialism provided a roadmap to unmaking the world that racism and its cousins — colonialism, class repression, inequality, apartheid — had so violently constructed. Omar had found ideas like Desai’s heady and inspiring, especially in the context of the conservative propaganda that emanated from both the state and his schools. Not surprisingly, the government drew a different conclusion and banned Desai from public life, placing him under house arrest and making it impossible for the promising student to earn a living. Omar and Desai lost touch after the banning, but Desai’s ideas became principles by which the younger man would try to live his life.

Holding to those ideals was never easy. Apartheid was relentless. First came the expulsion order. Then came the even more awful news that Desai — still in his twenties — had died. The press reported that he had walked into the Indian Ocean and drowned. The police called it suicide, since Desai could not swim, but rumours swirled that the government’s Special Branch had been involved. Desai had been “one of the best of the old guard here in Durban,” Omar mourned. “He taught me my politics.” […]

When trying to read or draw, Omar thought about the costs of struggle. He considered his family’s predicament and Desai’s death. He lost track of his task easily. He was frequently startled to find himself staring blankly at the paper tacked to his wall, or frozen with his head cocked, lost in the rain drumming on the roof. He yearned for something different, something better. Activists had once envisioned a future that broke totally with apartheid, colonialism, racism, and poverty. They had resisted the machinations of a powerful state, only to falter when the state had pushed back, with deadly force.

Desai was gone. What did his death mean, for Omar, for Durban, for South Africa? Omar was an artist, a reader, an observer, a quiet participant, developing his own critiques, theories, and responses to apartheid. He wanted to be a revolutionary, yet “my accomplishments amount to so little that an ant could stand on them.” That realisation arrested him. An anthill was something, however small; perhaps its tiny elevation might be a foundation.

He sought out like-minded others, a new generation of activists, a network like that frayed collective that had mourned Desai. He cultivated friendships with other artists from Durban and beyond. He celebrated their talents and learned from how they distilled and related their experiences. He went to galleries and cafés and listened to poetry. In his friends, he recognised the same frustrated energy, that determination that something had to change. They were poets, writers, artists. Sometimes cowed in public, in private spaces they imagined a different South Africa, a different world. They carried their own histories, their own traumas; Omar certainly carried his. Writing, reciting, drinking, drawing, debating, they sought a way through their wounded selves.

South Africa was big, its government massive, its power seemingly absolute. Omar was an ant. The state could crush him under foot. But the more he read, the more people he met, the more he was convinced that there were other ants, in rooms like his, in Durban, across the country, antennae prickling with invisible signals, moving around, coming to new alignments and renewed purposes. He was increasingly convinced, in time, “things [might] go like before,” back before he had met Desai, when there had been protests, marches, and fearless confrontations with the state.

He hunted for evidence in the streets, in his growing networks, in the newspapers, in his art, in his own self. Occasionally, his task appeared before him with remarkable clarity. “I want to forge links with the future,” he declared in his diary, so that “what they enjoy is what we wanted to enjoy.”

Time passed. He wrote and read, sketched and listened to the rain. He was sometimes melancholic, occasionally inspired, often stubbornly resolute. He argued with his family and sought solace in books, pens, paper and friends. The apartheid state made plans for his neighbourhood. Omar Badsha made plans of his own.

Available Light: Omar Badsha and the Struggle for Change in South Africa is published by Jacana.