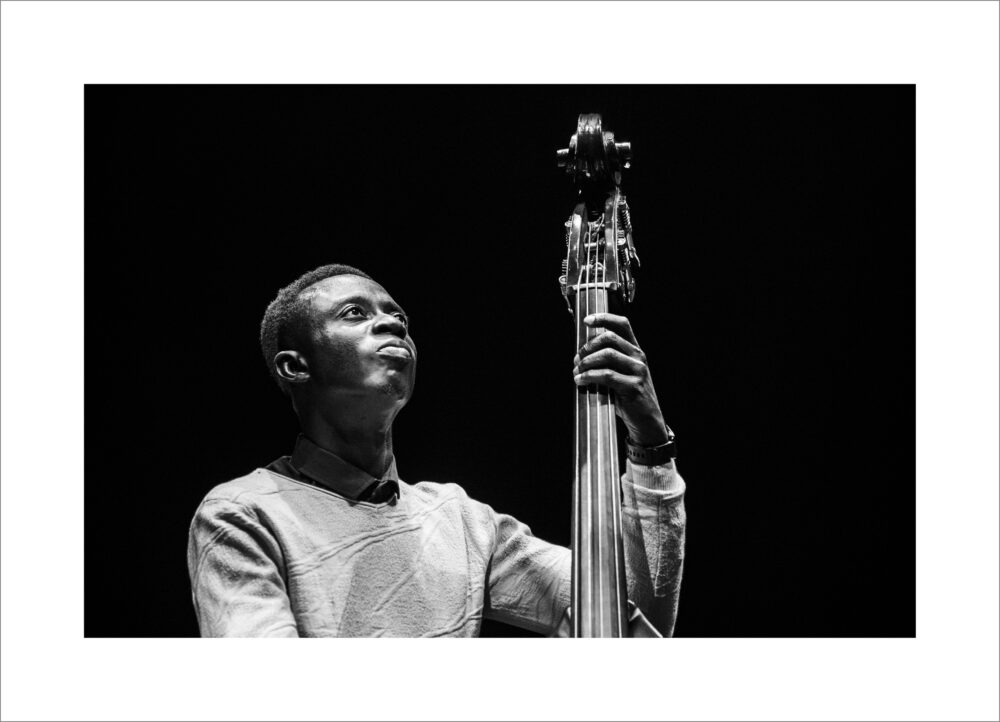

A moment in time: Images from Jonathon Rees’s show titled Stillness.

At this year’s National Arts Festival in Makhanda, I stumbled upon a quiet revelation in the Monument — a photographic exhibition titled Stillness, where images of jazz musicians mid-performance stood suspended in time — full of intensity, intimacy and grace.

The photographer behind them is Jonathon Rees. He might not be a household name in the South African art world just yet but his debut solo exhibition made a powerful case for the visual possibilities of live music.

Rees’s portraits are stark, focused and emotionally charged; they don’t just capture musicians playing music. They distil a moment of devotion, a flicker of transcendence, the quiet just before the applause.

The photographs feel like jazz itself — improvisational yet studied, free yet focused.

What makes his work all the more remarkable is that Rees is not a full-time photographer. He came to photography — and to jazz — as an outsider. And perhaps that’s exactly why his perspective is so refreshing.

When I spoke to him, he began, quite unexpectedly, with journalism.

“I studied journalism and history at Rhodes University,” he told me. “It was at the festival actually, late at night, in a smoky bar, that I discovered jazz. It absolutely moved me.”

This was in the 1980s, during apartheid. Rees remembers the jazz venues of that time as some of the only truly integrated spaces.

“It was mixed, but authentically mixed. It just felt natural — it felt like the world we wanted.”

And maybe that’s the thread running through his work — the longing for unity, beauty and presence.

Freeze frame: Photographs from Jonathon Rees’s exhibition Stillness which was on at the National Arts Festival in Makhanda.

Freeze frame: Photographs from Jonathon Rees’s exhibition Stillness which was on at the National Arts Festival in Makhanda.

Although he had always taken photographs, Rees never considered himself a professional. It wasn’t until 2016, when he attended the farewell concert of Max Luner, a young jazz drummer and the son of a friend, that something shifted.

“He played with Caroline Mhlanga, and I took photographs. That night gave me the bug. I realised I could make visual art out of live jazz performance. And that excited me.”

Rees didn’t grow up with art and music: “There were no paintings in our home and we didn’t really listen to music,” he told me.

That context, the absence of cultural exposure in his early life, makes his soulful connection to jazz and photography all the more poignant.

“I felt like I had an opportunity to be an artist in the musical world, even though I never imagined I’d be here,” he said.

And once he caught the bug, he chased it obsessively. Rees started attending jazz gigs around Johannesburg two, three, sometimes four nights a week, learning how to work with bad lighting, getting familiar with venues and musicians, and developing a style.

For the first five or six years, it was purely about learning.

“As an older person, that was really rewarding. It proved you can still learn something new later in life.”

He set out initially trying to capture full-band shots, faces, fingers, full instruments, but quickly realised that between lighting limitations, stage obstructions and constant movement, that approach wasn’t sustainable. Instead, he began to move closer, literally and metaphorically.

“I realised I was making portraits. I was focusing on the person and their concentration, their passion, their communication.”

Many of the images in Stillness are not of performance in the traditional sense. They show the moment after a solo, the breath before the applause.

A moment in time: Images from Jonathon Rees’s show titled Stillness.

A moment in time: Images from Jonathon Rees’s show titled Stillness.

Take the photo of musician Thandi Ntuli right after her final piano note. “She looks up, absolutely quiet. That moment before the clapping starts, that’s the stillness I’m after.”

And in another image, of Nduduzo Makhathini, taken on a freezing night at Constitution Hill, vapour rises from a musician’s mouth as he exhales into the cold.

“He was making a connection with someone else on stage. That’s why I love that image. You can feel the environment, the music and the intimacy,” Rees said.

These in-between moments when the musician steps back from the microphone or pauses between phrases are when he feels closest to his subject.

“It’s in those gaps that you really see someone.”

But stillness, he admits, is also something personal.

“I think I’m also looking for the stillness within myself. We live hectic lives and we need to find a way to be quiet over the chaos.”

Photography, as any journalist knows, is technical. In journalism school, we get a crash course at best. So, I asked Rees when he knew he’d taken a solid image and how he developed confidence in his craft.

“I look at a lot of other photographers,” he said. “There’s a strong tradition here — Ernest Cole, Cedric Nunn, Oscar Gutierrez. I admire them deeply.”

But, ultimately, it’s a matter of internal validation.

“I have to look at a picture and say: ‘This is good for me. This is the best I can do.’”

He has developed a recognisable visual style — tight black backgrounds, clean compositions and a singular focus on the musician’s face or hands.

“I don’t want clutter. I want the image to be clear and reflective of what I felt in that moment.”

And maybe that’s why his images don’t fall into the usual tropes of South African photojournalism —poverty, protest, pain.

“We’ve seen enough of that. I want to show people in their power.”

Stillness marks Rees’s first full exhibition. He’s done mini-shows before in a small town, in a hotel, but this was different.

“To show my work at the National Arts Festival, where I first discovered jazz and where I’ve come back year after year to shoot jazz, meant everything to me.”

Many of the musicians in the photo were performing at the festival. Some came to see the exhibition. Some gave feedback. Most, he says, were gracious and warm.

“You don’t always get feedback in a gallery space but I got enough from people I respect to feel validated. And it’s motivated me to keep going.”

Now, back in Johannesburg, Rees is planning to show Stillness again —possibly at Afrikan Freedom Station in Sophiatown.

He might tweak the selection after seeing how the images sat on the walls in Makhanda. But, mostly, the show will stay the same, with a few new additions.

He’s not slowing down.

“I’ve never worked so hard on anything in my life. And the question I ask myself constantly is: ‘Have I done my best?’ With this show, I believe I have.”

And that, perhaps, is where the real stillness lies — not just in the silence between two notes but in the quiet, unflinching pursuit of one’s own artistic truth.