Isadora and her mother Emily. Isadora was one of roughly 3 000 children in Brazil to be diagnosed with Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.

Emily was combing her baby daughter’s hair when she first felt the lumps. It was a week before Christmas, and she and her husband had taken their children to visit family. Her youngest daughter, Isadora, had been feverish and listless, unwilling to play or take a bottle. The lumps were clustered on the back of Isadora’s neck, the size of small beans.

At the emergency centre, the doctor found more lumps under Isadora’s arms and in her groin. The doctor urged Emily to take her daughter to a hospital as soon as she could.

Back home in Porto Alegre in southern Brazil, Emily watched as doctors hurried her daughter through medical tests. The lumps had grown. That night, Isadora was lying on a stretcher beside Emily when a doctor told her the news. Isadora had an aggressive form of leukaemia, a cancer that affects white blood cells and that is the most common kind of childhood cancer.

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) is the most common kind of childhood cancer, and Isadora was one of roughly 3 000 children in Brazil to be diagnosed with it in 2017. Her treatment would be gruelling: a cocktail of chemotherapy drugs that would leave her skeletal, vomiting and lethargic. One cancer doctor described this process as a fine art: to almost kill a child, but not quite.

Isadora, usually a bubbly baby, began to suffer side effects. Emily took hope from the idea that, although the drugs were making her daughter sick, they were also curing her.

One of the most important chemotherapy drugs in Isadora’s concoction was asparaginase. It stops cancer cells from dividing and growing. Without it, patients face a dramatically reduced chance of survival. But in Brazil, the drug was already at the heart of a national scandal.

Emily’s daughter would be the last child in the hospital to receive a particular brand called Leuginase. Later that year, Brazilian doctors — including some looking after Isadora — would confirm that Leuginase was nowhere near as good as it should have been. What’s more, it was contaminated. Eventually, the Brazilian government was ordered to remove Leuginase from hospital shelves.

It should have been the end of the scandal. Instead, it was just the beginning.

Reporting by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, in partnership with STAT, reveals that at least a dozen brands of asparaginase have been proven to be poor quality, with 10 still on the market. In some cases brands fell well below the standard needed to treat cancer. Many have also been found to contain contaminants such as bacteria that could be harmful to patients. A spokesperson for Leuginase’s manufacturer, Beijing SL Pharmaceutical, said their drug is tested by Chinese regulators and assessed in-house, where – he claimed – quality results have stayed within statutory limits over the past decade.

Emily and her daughter Isadora.

Emily and her daughter Isadora.

In the past five years these poor-quality brands have been shipped to more than 90 countries. Many receiving the drugs are low- and middle-income nations without strict regulatory authorities, but in several instances substandard drugs have been imported into Western Europe and given to patients in Italy.

At least seven manufacturers have continued to sell their products despite being warned that they do not meet minimum manufacturing quality standards. Experts estimate 70 000 children around the world are at risk, as contaminated and ineffective asparaginase slips through global safety nets.

“What’s happening here is a disaster,” said Professor Vaskar Saha, director of the Tata Translational Cancer Research Centre in Kolkata. The vast majority of children with ALL are in poor countries. “This is an issue of money, resources, and equity.”

Experts believe that Brazil’s experience should have been a warning to the world of the growing threat posed by substandard asparaginase. Instead, lax regulation and oversight has allowed these products to proliferate, and little has been done to increase access to high-quality drugs for the world’s poorest. As a global shortage of the drug continues, experts fear that high-income countries may also be compelled, like Italy, to buy untested products.

Doctors may have no idea if they are prescribing poor-quality asparaginase — or what else could be in those vials. As long as this continues, sick children’s lives hang in the balance.

Fight for survival

In 2018, shortly after Brazilian courts banned Leuginase, the substandard brand of asparaginase, Professor Silvia Brandalise received a package from Haiti. Brandalise, a children’s oncologist in Brazil, had long been suspicious of Leuginase. She had tested the drug in mice, and came under fire for speaking up when she found it was dangerously defective.

The package was sent by the head of Haiti’s only paediatric cancer department. It contained a single vial of asparaginase.

Since asparaginase was introduced in the 1960s, survival rates for children with ALL, Isadora’s cancer, have risen to about 90% in wealthy countries. In Haiti, Dr Pascale Gassant saw only 15 or so patients a year in her department, a fraction of the children with the disease in her country. Her ward did not have a 90% survival rate.

Nonetheless, she had had good success with her patients. That was until her hospital switched its brand of asparaginase.

Since then, Gassant had watched her patients’ chances of recovery plummet. Children she would once have been optimistic about — children who were otherwise healthy, and who had arrived early enough that treatment could save them — were dying. The hospital’s survival rate for that cancer was just 3.5%.

In Brazil, Brandalise’s colleagues tested the samples. Her worst fears were confirmed. Like the Brazilian Leuginase, the Haitian drug was contaminated with byproducts that could cause side effects and even impede treatment. Gassant’s silver bullet was useless. Her patients did not stand a chance.

Something else caught Brandalise’s attention. The Haitian product was made by Beijing SL Pharmaceutical, the same Chinese company that manufactured Brazil’s Leuginase. If poor quality asparaginase had spread to Haiti, how many more countries had it reached?

She had no way to know it, but bad asparaginase had already begun to flood the world. In 2018 alone, analysis by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism shows that poor quality brands made their way to more than 40 countries in Europe, South America, Asia, Africa and the Middle East.

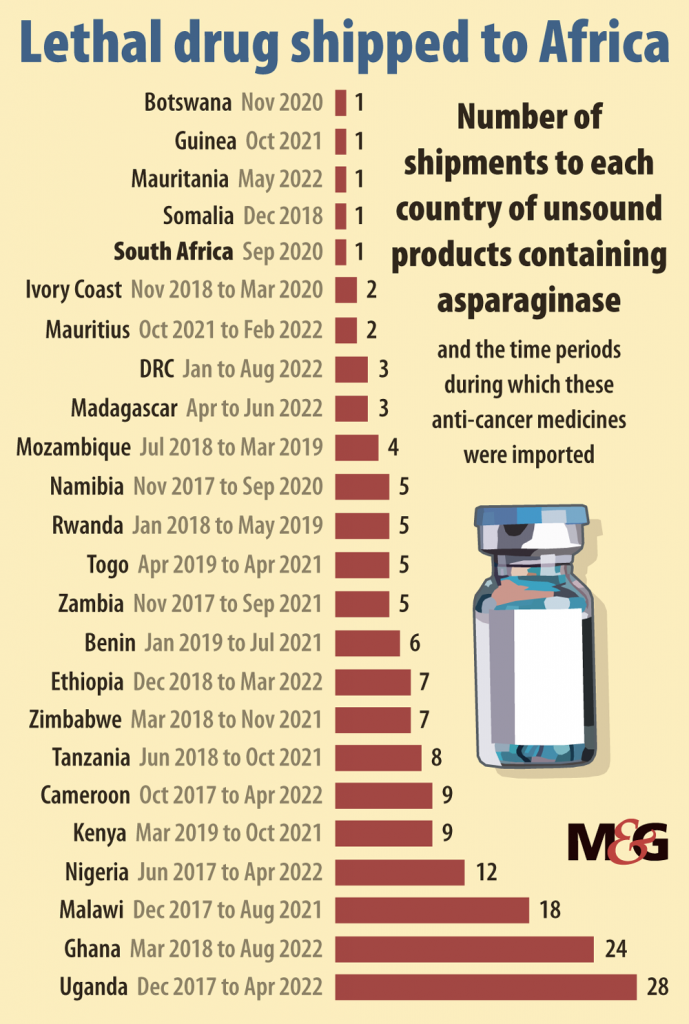

Worse, in the past five years substandard asparaginase has spread to almost 100 countries, from Armenia to Zimbabwe. Shipping data suggests that countries including Nepal, Ecuador and the United Arab Emirates have received the most shipments of these brands. Nearly half the countries of Africa have received substandard drugs.

A representative from Beijing SL Pharmaceutical said the company has produced asparaginase for a dozen countries over the past decade. “Doctors in China and around the world have been using our products and none of them, other than these individuals in Brazil, has ever reported any quality-related problems,” he said, noting the company’s asparaginase is tested by Chinese drug regulators and in-house, where — he claimed — results have stayed well within statutory limits over the past decade. He disputed the Brazilian doctors’ findings, calling them “shocking” and “absurd”.

He added that the company had never sold its asparaginase in Haiti, and offered several theories on how it could have ended up there: it could have been counterfeit, expired or sold on by South American distributors. He said Beijing SL Pharmaceutical would conduct a thorough investigation of all its asparaginase sold abroad.

Professor Silvia Brandalise

Professor Silvia Brandalise

Market failure

For years, cheaper, good-quality asparaginase was available to low- and middle-income countries, where 90% of children with cancer live. But in the past decade, major manufacturers have increased their prices or stopped making asparaginase altogether. The result is a terrifying global shortage of one of the world’s key cancer medicines, and a crisis that is disproportionately affecting the countries that need it the most.

There are several different types of asparaginase. “Native” asparaginase is made from Escherichia coli (E coli), a bacterium more commonly associated with nasty sickness than saving lives. Turning the bacterium into medicine is complicated and costly, and even good-quality asparaginase can cause side effects, including severe allergic reactions.

For this reason, doctors prefer to use modified versions of asparaginase. These are less likely to cause allergic reactions, but are much more expensive. In Europe and North America, two brands — Oncaspar and Spectrila — are widely used. (Both have consistently passed quality tests.)

For patients who experience serious reactions to these forms, there is another type: Erwinia asparaginase. But only two companies make trusted brands and supplies have frequently been short since 2011.

Manufacturers are increasingly focused on their higher-priced modified products. The cost of these “gold-standard” products has ballooned well beyond what poorer countries can afford.

The Brazilian government was ordered to remove Leuginase from hospital shelves.

The Brazilian government was ordered to remove Leuginase from hospital shelves.

Take Oncaspar. Takeovers and mergers mean that the drug has passed through five different pharma companies in the last 15 years, with corresponding price hikes. Published data shows that a single vial of Oncaspar cost $1 700 in the US in 2015. The following year, when one company merged with another, that price surged to $18 000. Today a vial of Oncaspar, now owned by the French company Servier, is listed for as much as $24 000 on US websites.

Another modified brand, Spectrila, is said to cost $500 a vial in Chile, and roughly the same in the UK.

Unable to access these products, hospitals in low-and middle-income countries often use cheaper, native asparaginase. Until recently there were at least two good, affordable brands. But the first was discontinued in 2012 due, the company said, to “ongoing manufacturing challenges”. The second was discontinued in 2020, after the sole manufacturer in Japan had its certification of quality revoked.

As these products disappeared, so too did many doctors’ hopes of prescribing asparaginase to their patients. None of the leading manufacturers of asparaginase have stepped in to produce an affordable native form. A market analysis from 2021 found that global demand for the drug was too small to motivate companies to improve their quality, or to encourage other manufacturers to begin producing it.

“Why suffer?” said Professor Scott Howard, secretary general of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology. “If you’re just making a few dollars per vial, and yet people still criticise you if anything goes wrong …” Is it any wonder, he suggested, that high-quality manufacturers are steering clear?

Short supply

Professor Carmelo Rizzari had never experienced a shortage of asparaginase until 2018, when a pharmacist at his hospital in Milan, Italy, told him they could not get hold of Oncaspar. “We asked them to explore any possible solutions,” Rizzari recalled. Could they get some vials from another hospital? Could they find an alternative product?

Not long after, the drug arrived in the pharmacy — but Rizzari had never used the Indian-made brand, Aspatero, before.

Rizzari gave it to his patients. As chance would have it, the 12 children were part of international studies that meant their treatment was being closely monitored. Later analysis revealed low levels of asparaginase activity in half of Rizzari’s patients — something the researchers say probably led to the drug working inadequately. Two children experienced side-effects.

The pharmacist soon found a supply of Oncaspar, and Rizzari swapped his patients back to the gold-standard brand. All survived. But when data from the studies revealed what had transpired, Rizzari was disturbed. “I was convinced the drug we imported was as good as the brand we were using before,” he said.

Rizzari’s hospital, Fondazione MBBM, said its request to import Aspatero was authorised by the Italian drug regulator, and that to the best of its knowledge other Italian hospitals imported the same drug in the “same period and for the same reasons”, a country-wide Oncaspar shortage.

“Failure to administer the drug would certainly have made the treatment less effective and reduced the chances of children’s recovery,” a spokesperson said. “We had no possibilities to foresee any qualitative deficits.” They added that the side effects “did not pose severe risk” to patients and were the same as those usually seen in patients receiving other asparaginase products.

The Italian drug regulatory agency denied it had authorised the import of Aspatero from India. Italy’s health ministry and its customs agency declined to comment.

If Rizzari felt his experience was a single worrying slip in Italy’s stringent standards, he was wrong. The Bureau has found that at least 10 other Italian hospitals have purchased poor-quality asparaginase in the past five years. It is unclear how many patients have been affected.

While it is not unusual for countries to use legal loopholes to bring in unauthorised products during a sudden shortage, or for patients with rare diseases, Italy’s actions have raised questions about the security of the country’s drug supply chain.

Italian doctors were shocked to learn that the brand of asparaginase they have been administering to their patients, Celginase, has been found to be substandard. “We trust the ministry of health and [regulatory agency] AIFA have already checked the safety and efficacy,” said Luigi Rigacci, a haematologist at San Camillo Forlanini in Rome, one of Italy’s major public hospitals. “It would be really disappointing to know there are no thorough quality controls on the foreign asparaginase we’ve been using.”

While Oncaspar cost €2 500 a vial, San Camillo Forlanini bought Celginase for just €15. Hospital documents show San Camillo Forlanini purchased Celginase in 2020 and 2022. The hospital said it had bought Celginase in compliance with relevant regulations.

Bad batches

In April 2019, not long after Rizzari’s experience in Italy, a professor working in the infection control unit at Saudi Arabia’s King Abdulaziz University Hospital sent a memo to the hospital director. Five young patients had developed a high fever after taking an Indian-made asparaginase. One died.

This had never happened when the hospital was using a US-made brand, the professor, Tariq Madani, reported. He had run tests on the new drug. The samples contained high levels of two kinds of bacterium, which, Madani concluded, had led to the children’s sudden fever.

Under the heading “Recommendations”, Madani urged several courses of action. First, to stop using the brand and to find an alternative source. Second, to send an urgent memo to the Saudi Food and Drug Authority to recall “all bottles used anywhere in the kingdom”. And finally, to alert the manufacturing company so that they could recall bottles from any other countries. It is not clear if all of these recommendations were followed. Neither King Abdulaziz University Hospital nor the Saudi health ministry responded to requests for comment.

The Bureau’s analysis of shipping data shows that the brand, Pegapar, has continued to be exported from India, entering at least nine countries since mid-2019, soon after Madani wrote his memo. During that time, its manufacturer has directly exported the drug to Ecuador, Nepal, Sri Lanka and the UAE. (Pegapar’s manufacturer did not respond to a request for comment.)

Contamination of asparaginase with harmful bacteria is potentially deadly. Cancer treatment leaves children with significantly weakened immune systems, making them more prone to infections and other serious complications. “It’s never good to have a bacteria in your bloodstream,” the oncology expert Scott Howard said. “It’s far worse if you have low blood counts [of immune cells].”

Infections hit harder on a paediatric oncology ward, often requiring intensive care. If a child receiving chemotherapy gets an infection, the cancer treatment stops until they are better. Howard explained: “The patient could survive [the infection] and might have missed three weeks or four weeks of treatment.”

Pegapar is not the only brand that has been found to be contaminated with bacteria. In August and October 2020, the Chilean health ministry issued two alerts against Onconase in quick succession. Both batches were found to contain bacteria after patients suffered fevers.

In 2021, the manufacturer of a gold-standard brand put out a letter warning that Onconase had “failed to meet almost all purity specification parameters”, and that “striking quality defects” were presumably leading to ineffective treatment and severe side effects.

Even so, shipping data analysis shows Onconase has been imported into Chile at least nine times since its health ministry alerts. Government records show the brand has been distributed more than 70 times to more than a dozen different hospitals since late 2020. Some were still receiving Onconase as recently as last October.

The Chilean health ministry said its alerts concerned only specific batches of Onconase, and did not require “restrictions or withdrawals of other batches”. The ministry said it had carried out routine quality controls on all batches of Onconase and had refused the manufacturer’s latest request to import a modified version of the brand.

The world’s pharmacy

India and its pharmaceutical industry plays a vital role in ensuring people across the world can access affordable medicine. It is the world’s largest provider of generic drugs — essentially copies of branded drugs, made to be cheaper but just as safe and effective. Globally, it is known as “the world’s pharmacy”.

The majority of its products are safe and work well. But for decades, the Indian generics industry has been dogged by quality scandals.

Most generics produced by India are “small molecule” drugs, chemicals that are copied exactly but sold for less — think of the aspirin you can pick up for pain in a pharmacy, or omeprazole for heartburn. Asparaginase, though, is a biologic: a drug made from a living organism. Biologics and their generic versions (known as biosimilars) have much more complex and expensive manufacturing processes than most small molecule drugs.

In recent years, a complex network of Indian suppliers have sought to capitalise on chronic shortages of gold-standard asparaginase and the increasing desperation for affordable products.

It was some of these new brands that fell under Professor Vaskar Saha’s scrutiny. Saha was working at Tata Medical Centre, a specialist cancer hospital in Kolkata, when he began to examine the quality of brands available on the Indian market. He tested seven products. Not a single one met minimum manufacturing quality standards.

In five brands, drug strength was lower than expected. All seven had purity problems. Nearly 20% of patients who were given a widely used brand developed allergic reactions and had to be taken off the drug completely.

Saha was deeply concerned. Low drug activity levels of the kind he had observed in his research were “likely to compromise” patients’ ultimate survival, he wrote. He was also keenly aware of the inequalities between his patients in India and those in his second home, the UK. In the paper’s conclusion, he noted that drug quality was potentially a “significant determinant” in the differing patient outcomes in high- and low-income nations. In lay terms: sick children in poor countries could be dying in large part because of bad drugs.

Saha alerted all the manufacturers to what he had found. Just three replied, saying they wanted to do better. All seven products remain on the global market and were sent to countries around the world in 2022.

“There are only a handful of Indian companies that actually have capacity and capability to manufacture biologics,” said Dinesh Thakur, a drug safety advocate and former generics industry whistleblower. “It’s a completely different ballgame.”

Nonetheless, according to a national database, the 11 Indian asparaginase manufacturers investigated by the Bureau have received important, World Health Organisation quality-assurance certifications. While the WHO sets the framework for these schemes, responsibility for assessing facilities and issuing the certification lies with national governments: in this case, the Indian health ministry.

At least two companies producing poor-quality asparaginase claim to be “approved” by or “compliant” with western regulatory authorities such as those in the US and UK.

But the first, Virchow Biotech, which makes Pegapar, has been inspected by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In 2015, the agency found “objectionable conditions or practices” without taking regulatory action. The FDA has not approved Pegapar for sale in the US.

The second, United Biotech, which makes Onconase, is not listed on the FDA’s database of registered drug manufacturers. The FDA refused an import from the company in 2013, and has not inspected their manufacturing plants or authorised their products. The UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency said it has not granted United Biotech any good manufacturing practices certification. (Virchow Biotech and United Biotech did not respond to a request for comment.)

The Indian-made asparaginase investigated by the Bureau sells for just a fraction of the price of gold-standard brands. One senior oncologist from Latin America said Onconase was marketed at one-tenth the price of Oncaspar. A Bureau reporter posing as a buyer was recently offered Indian-made asparaginase for as little as $7 a vial.

Wholesalers also provided documentation from the manufacturers purporting to verify their products’ quality. But right now, Thakur said, the quality certification provided by manufacturers to purchasing countries is “a piece of paper from the Indian regulators saying the product is manufactured under good manufacturing practice conditions. How they establish that is not known to anyone.”

He thinks that the Indian government should review and strengthen its drug approval process, particularly for biologics, to ensure strict standards are being met. “The regulator has no clue what they’re doing, because the way we should approve biosimilars is very different from the way we should approve regular small molecule generic drugs,” he said.

In July, the Indian regulatory agency sent a letter to its regional drug controllers instructing them to look into the issue of poor-quality asparaginase and take “appropriate action”. The Indian ministry of health and Indian drug regulatory agency did not respond to a request for comment, and so far, little appears to have been done.

Hospitals in low-and middle-income countries often use cheaper, native asparaginase.

Hospitals in low-and middle-income countries often use cheaper, native asparaginase.

No quality control

Without proper checks before the drugs are sold, a greater burden falls on purchasing governments to improve quality checks at home. Ed Vreeke, executive director of Quamed, a nonprofit aiming to improve access to high-quality medicines, said that some Indian manufacturers are profiting to “the maximum extent” from the “lack of regulation in many countries that they export to”.

He thinks that local regulators need more support to improve their ability to assure the quality of medicines, from licensing through to laboratory tests and patient monitoring. While many countries do batch-test medicines on arrival, “the quality of the tests are not good”, Vreeke said. “[Pharma companies] know they can export whatever they want.”

Cost-cutting may be driving wealthier governments who could secure more expensive, trusted brands to choose low-cost alternatives. Since its asparaginase scandal, the Brazilian government has changed regulations to allow its ministry of health to buy drugs that have not been proven safe and effective, even if approved products are available in the country. Experts have questioned whether that decision was driven by anything other than reducing costs. (The Brazilian ministry of health did not respond to a request for comment.)

But the high price of gold-standard products puts them out of reach for much of the rest of the world. “In my dream I’d be giving all children pegylated [modified] asparaginase,” said Professor Simon Bailey, a children’s oncologist who has advised on treating patients in East Africa. In one instance, the team was alerted to potential defects in their asparaginase.

After weighing the risks, they stopped giving their patients the drug and replaced it with another chemotherapy. “That’s not ideal,” Bailey said. But gold-standard asparaginase was not an option. “It’s just not affordable.”

Neither of the major manufacturers of gold-standard asparaginase offer programmes to help poorer governments afford their products. Servier, which makes Oncaspar, did not respond to a request for comment. Volker Bahr, director of global political affairs at Medac, which makes Spectrila, told the Bureau that while the company wants to supply more countries and is “actively working” to expand its manufacturing capacity, it could not currently keep up with global demand.

Given the global nature of the crisis, and the fact that asparaginase is listed as essential by the WHO, some have suggested the organisation should do more to boost access to good-quality asparaginase.

The WHO hosts a global monitoring system for fake and substandard drugs, and provides technical support in emergencies. Although it can issue medical product alerts, it does not have the power to reprimand countries for exporting poor-quality medicine, or close down manufacturers.

“WHO is a political organisation as much as it’s a health organisation,” Dinesh Thakur said. “They don’t want to step on individual countries’ shoes.”

The WHO relies on countries to report incidents to its monitoring system, and some are more willing to do that than others. Thakur suggested that reported cases in India were just the tip of the iceberg. “If the country doesn’t report this properly, there’s very little the WHO can do.”

Rutendo Kuwana, head of the WHO’s substandard and falsified medicines team, told the Bureau they do not have any record of substandard or fake asparaginase products. While the team was aware of “anecdotal reports” and scientific publications raising concerns about some products, “no definitive product information is available for possible follow up with competent authorities”. Kuwana said it was the responsibility of country regulators to initially investigate reports of substandard drugs, while the WHO would offer support “on request”.

In Brazil, Silvia Brandalise’s colleague Dr Pedro de Campos-Lima said his country’s asparaginase scandal shows the “fragility of our system right now”. But if governments and global health bodies work together, he said, “there is still time to stop an even more catastrophic situation”.

Roughly 10% of medicines sold in low and middle-income countries are thought to be fake or substandard, with tragic consequences. In October, the deaths of nearly 70 children in Gambia were linked to an Indian-made cough syrup. Last month, 18 children died in Uzbekistan after taking another Indian-made cough syrup. Fixing the systemic issues that have allowed poor-quality asparaginase to spread could help patients far beyond child cancer wards.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)Facing the future

Stemming the tide of poor-quality asparaginase will take global cooperation, money and willpower. While long-term solutions may feel out of reach, a handful of measures to help children who need the drug now are taking shape.

In December 2021, the WHO and St Jude Children’s Research Hospital announced plans to improve the global supply of quality childhood cancer medicines, with asparaginase a priority. A new platform will act as a purchaser on behalf of low- and middle-income countries, giving quality manufacturers a reliable source of demand. In turn, they may be more willing to offer competitive prices for bulk orders. The result should benefit everyone.

The platform has secured $200 million over the next five years, and expects to send medicines to the first 12 countries. St Jude predicts about 120 000 children could benefit by the end of 2027. “The solution really is completely restructuring the market dynamics around childhood cancer,” said André Ilbawi, WHO’s technical lead in cancer control. “This is a once in a lifetime opportunity.”

For those still relying on untested brands, one short-term solution could be to assess asparaginase as patients are being treated with it in hospitals. In Brazil, one cancer doctor, Professor Mariana Bohns Michalowski, has developed a simple and inexpensive way to use patients’ blood to check if the asparaginase works well or not. Her team has trained researchers at eight centres in Brazil and one in Colombia so far.

In India, Vaskar Saha is working with the three manufacturers who responded to his research to help improve their asparaginase products. He hopes that a collaborative approach will help spur Indian manufacturers to create an affordable asparaginase on par with gold-standard brands. “We can point fingers at the industry,” he says, “But while we might find the solution, they’re the ones who are going to deliver it.”

The fastest solution to the crisis could be to convince quality manufacturers to lower their prices — at least for countries who cannot afford them. While this may seem like a non-starter, one leading oncologist said he had argued with both Servier and Medac that selling their products at a price only rich countries could pay limited their profits. “I said, if you dropped your prices by half and sold to the rest of the world, you would make the same amount of money, if not more,” he said. But the companies refused. (Servier did not respond to a request for comment. A Medac spokesperson said the company declined to comment on the company’s drug pricing.)

For now, doctors will have to continue to use what they can get, and parents and children will continue to suffer the consequences.

A few months ago, outside a small house in the hills of southern Brazil, Emily was holding her daughter. Isadora had survived. After receiving eight doses of Leuginase and responding badly, doctors had been able to switch her onto a gold-standard product.

“We went for an appointment at the hospital yesterday,” Emily said. “Her test results were all good.” Isadora recently told her teachers that she wants to be a cancer doctor when she grows up.

Some 9 600km away, in Barcelona, a group of child cancer specialists met for their annual conference. On the first morning, they heard about data collected by Professor Federico Antillon, a Guatemalan oncologist. The research detailed the survival rates of children at his hospital who had received three different treatments: a gold-standard brand of asparaginase, asparaginase from India, or no asparaginase at all.

The results were stark. For children classed “high” or “medium” risk, survival rates for those given asparaginase from India were as low as those who did not receive any asparaginase.

There are caveats to consider in Antillon’s report. It features only a small number of children, and his findings are not yet peer-reviewed or published.

But to Professor Ronald Barr, a veteran child cancer specialist who presented Antillon’s findings, it was “simply another example” of how vital good-quality asparaginase was to children’s survival. “The system at large, with all its complexities, has failed these families,” he said.

Not far from the auditorium where Barr had spoken, a gaggle of eager sales people were gathering. They worked for a Colombian pharmaceutical company and were in Barcelona to sell asparaginase. With smooth sales patter and glossy leaflets, the sales reps explained how they could provide native, modified or Erwinia asparaginase. They said their products were marketed in countries including Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and Peru, although they hoped to expand.

Given the turbulent history of this crucial drug, you might expect them to be eager to share proof that their products are safe and effective. The company had given conference organisers paperwork showing their drugs had been authorised for import into Colombia, and that their asparaginase products were made in India and China. But on closer inspection, the documents revealed that one was made by none other than Beijing SL Pharmaceutical, the same company that manufactured Brazil’s Leuginase.

The Bureau asked the Colombian company to provide evidence that their product works and is safe. Their response was a letter threatening legal action if we published this story. — Additional reporting: Jill Langlois, Benjamín Miranda, Sam Horti, Ben Stockton.

This article is part of the Bureau of Investigative Journalism’s Global Health project, which has several funders including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. None of the funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output. You can read the bureau’s full investigation here. [LINK TK]