Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi says medical aids cost too much. Will tax alone be enough to pay for NHI? We look at the numbers. (GCIS)

Medical aid costs too much, Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi said at a press briefing in Kempton Park last week, speaking about the government’s plans for acting on the recommendations of the Competition Commission’s inquiry into the cost of private healthcare.

The news is not new, though; it’s what the inquiry’s report highlighted too — five years ago already.

The rate at which medical care prices have increased over the past few years is “far, far higher than the general consumer price index”, said Motsoaledi. (Consumer inflation was at 3.2% in January, whereas inflation for healthcare costs was almost triple at 9.3%.)

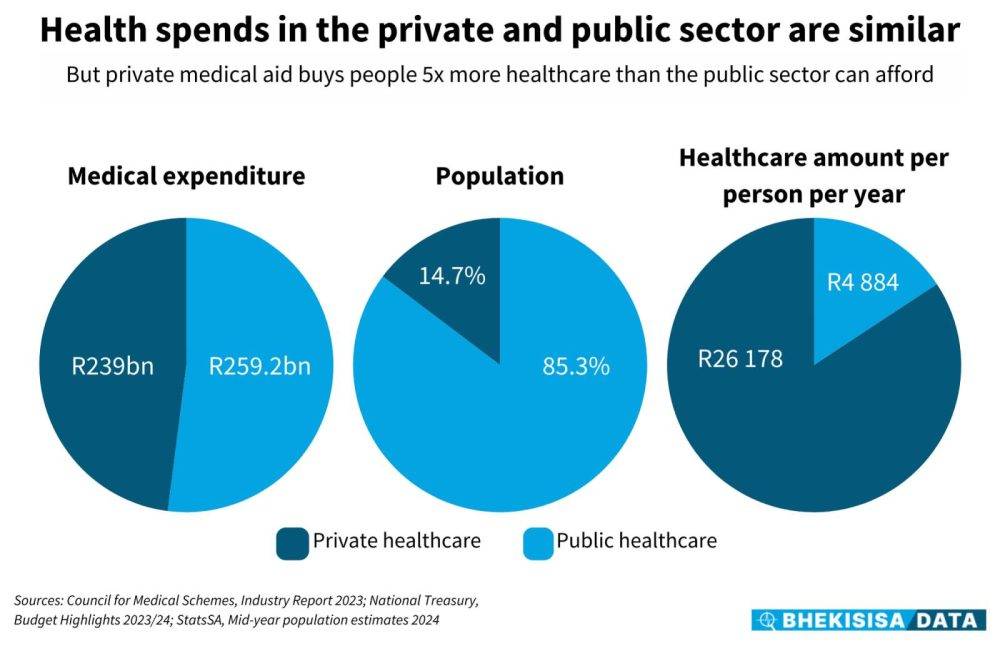

Indeed, only about 15% of people in South Africa belong (or probably can afford to belong) to a medical scheme, which makes it possible for them to go to private doctors. The remaining 85% of the population depend on public health services.

The government’s plan to make good on this is to roll out National Health Insurance (NHI) as a way to give everyone in the country the same healthcare, regardless of whether they can pay for it or not. It will essentially be a big state-run fund that will pay for people’s health services. Private medical schemes, in their current form, will not exist and they will only be allowed to cover services that the government doesn’t. (The package of services that the NHI will pay for is not yet known, though.)

But healthcare costs money — everywhere, not just in South Africa.

For example, the international auditing firm PwC projected earlier — before US politics upended many carts — that Americans will have to fork out 7.5% more this year to cover their medical costs than last year. This is more than double the roughly 3% mark where the US’s general consumer inflation is hovering at the moment.

What could the numbers mean for South Africans — and would the government be able to afford quality healthcare for all?

We looked at some options, using what we know about health spending in 2023 and what we think are reasonable assumptions, for how the pie could be sliced in future.

Here are our sums.

One country, two worlds

South Africa’s health system operates at two extremes.

In 2023, 9.13 million people belonged to a private medical scheme, which was about 15% of a total population of just over 62 million. The other 85% of South Africans — about 53 million people — probably relied mostly on free health services from the government.

Figures from the Council of Medical Schemes show that R239 billion was paid to cover members’ claims in that year, most to private health services. We therefore take being part of a medical aid as a reasonable proxy for using private healthcare.

Dividing R239 billion across 9.13 million people means about R26 000 would have been available to spend on each beneficiary’s care (the council’s report shows the actual average was slightly higher at R26 400.)

The situation in the public sector looks very different. Having just over R259 billion available in the health budget in 2023 to cover 85% of the population — 53 million people — means that each person could get about R4 900 of medical care — a fifth of what was available in the private sector.

Switching the thinking

There are different ways money for health services can be divided among a country’s citizens, though, and making good care available to all doesn’t have to mean that medical schemes can’t exist — or that everyone must get services for free.

In Germany, for example, the law says everyone must pay for health insurance. Most choose to pay for the state-subsidised medical aid, but people who earn above a certain threshold or those who are self-employed, can also opt to belong to a private medical scheme.

Healthcare is therefore funded partly by tax money and partly by people’s insurance premiums, and, in 2017, three-quarters of health spend was in the public system, with 57% of that from people who paid for state health insurance.

To think about how money for healthcare could be spent in South Africa, let’s start by considering a situation where no private care is available and the government has to foot everyone’s medical bills just from the tax money available in the health budget.

Working on 2023 figures, there’d be about R4 200 available per person (point A on the graph). Everyone would be worse off — both the 85% of the population currently relying on the public system, and getting about R4 900 worth of care (point B), and the 15% who use private healthcare and could buy about R26 000 worth of services (point F).

An alternative could be to add together the money available for public spending (R259.2 billion for 2023) and the amount paid towards private healthcare (R239 billion that year) and divide the total pot equally between the population (point C). That would mean roughly R8 000 is available for everyone — leaving people relying on public doctors 1.5 times better off than now, but those using private services about three times worse off.

Another option could be to add the two spends together and divide it by two to get to a fairer average amount that should be available to everyone (point E). This would work out to about R15 500 per person. People currently relying on the public sector would be able to get three times the value of services they used to and those in the private sector would have to do with about 1.7 times less.

But to give this to the entire population, a total of almost R966 billion should be available, and the government would therefore have to get about R468 billion extra somewhere to cover the shortfall.

Perhaps a more attainable way to get to a fairer situation would be to have about R11 750 available for everyone, which is halfway between R8 000 and R15 500 per person (point D). It would make twice as much available to people who always used to have to go to state doctors and about half of what those in private care were used to.

That would mean a total kitty of about R732 billion would be needed for healthcare in South Africa based on 2023 figures. If the sum of what was available from treasury (R259.2 billion) and what people paid privately (R239 billion) are subtracted, it leaves a gap of about R234 billion that the government would have to fill somehow.

Death and taxes

Funding universal healthcare simply by charging more tax — as is the current plan for NHI — is unworkable, says the Universal Healthcare Access Coalition, a group made up of organisations that represent health professionals from both the private and private sector.

That’s because the economy isn’t growing much at the moment, which means businesses make only small profits after covering their costs, and so there’s less tax that can be paid to the state. The situation also means lower pay rises for workers — if at all — and less chance of extra tax to fill the government’s purse.

A better plan, says the coalition in its proposal, is to get to a system where there’s a state-sponsored medical scheme that people can belong to (and pay for), alongside private medical aids. But the government’s fund has to be as good and well run as private plans so that it’s an attractive, yet affordable, option. In this way the quality and efficiency in the public and private health systems could gradually become more alike.

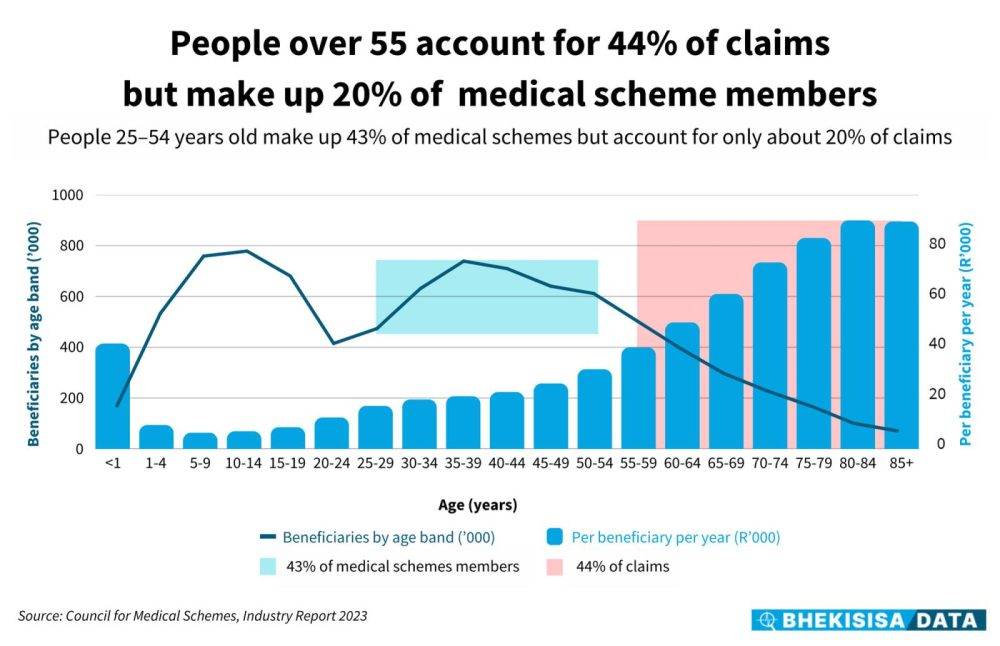

Moreover, South Africans are living longer and in 20 years’ time the share of the population over 60 is expected to be close to 15%, compared with the 10% it is now. On top of that, the number of people with noncommunicable diseases such as cancer, diabetes and heart problems linked to high blood pressure is growing — and the country is failing to stop the trend.

This can be bad news if medical costs have to be covered from a small budget.

A general principle in health insurance is that each person’s premium goes into a central pot. Not everyone claims for the full amount they contributed in a year, and so the leftover can subsidise people whose claims are more than what they contributed in a year, for example elderly people or those with illnesses that are expensive to treat.

But if the proportion of people who need extra healthcare grows, such as the elderly or those with chronic diseases, while the number of people who pay the biggest part into the pool shrinks — as could be the case in South Africa if health cover for all has to be covered by tax money alone — everyone will have to do with less.

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.