In the leafy office park not far from Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital, you’ll find them just past the security boom. Dozens of vehicles, leftovers from what were once busy, purposeful operations, sitting under the Highveld sun. Engines dead and tyres flat.

A few months ago, these brightly painted trucks and trailers emblazoned with Pepfar and USAid logos were on the move — part of a push to take HIV services to groups of people that government clinics often didn’t reach. But that was before US President Donald Trump abruptly stopped all Pepfar funding for HIV and TB projects which reached South Africa through the United States Agency for International Aid, USAid, in February.

The rainy Jozi summer and months of doing nothing have left rust spidering from cracks and leaves piling up on windscreens. Parked in a neat row, vehicles from one such organisation, the Anova Health Institute, the nonprofit in South Africa that received the most money from the US government’s Aids fund, Pepfar, have plastic tape strung between them, flapping in the wind like something out of a crime scene.

NO MORE: Mobile clinics that the US government funded to travel to communities for HIV services are now gathering dust in a Johannesburg parking lot. (Anna-Maria van Niekerk)

NO MORE: Mobile clinics that the US government funded to travel to communities for HIV services are now gathering dust in a Johannesburg parking lot. (Anna-Maria van Niekerk)

The parking lot is a metaphor for the crisis that has pitted the government against HIV activists and researchers, who warn we’ve entered another era of denialism, courtesy of the Trump administration.

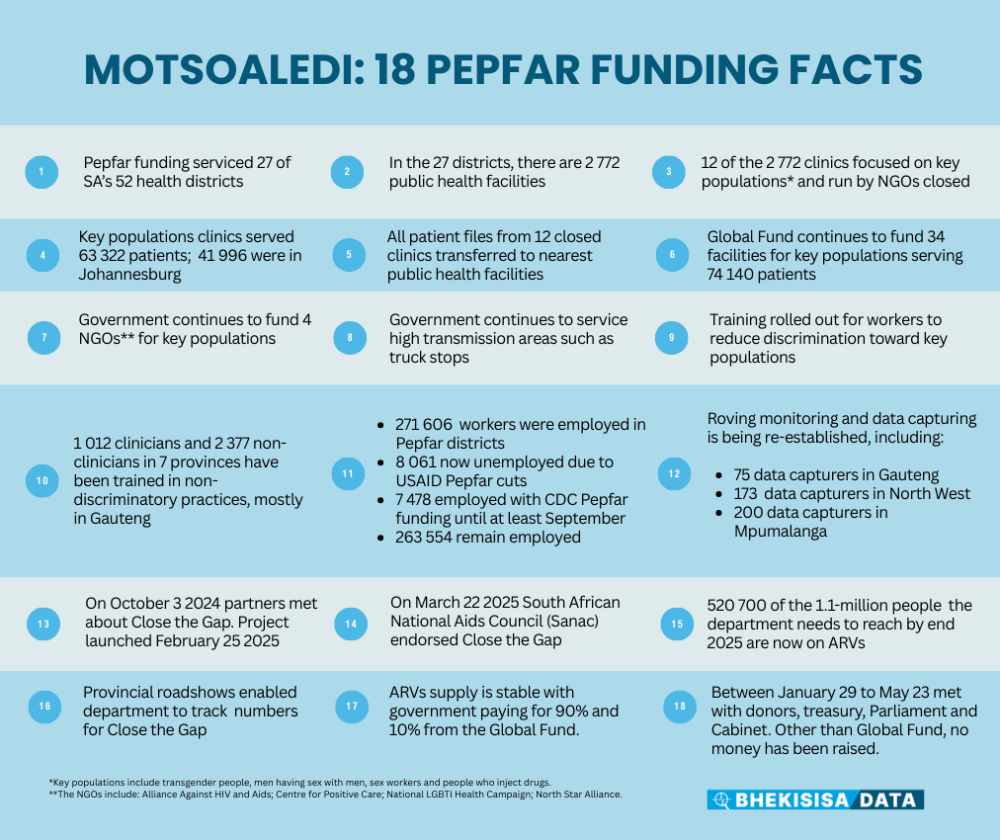

At a press conference last week, Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi gave a public tongue-lashing to the media, activists and researchers, accusing them of making an “AfriForum-style” scene to “spread disinformation”.

But unlike his predecessor, Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, who denied the link between HIV and Aids and propagated false cures such as beetroot and garlic, Motsoaledi is a man of science and evidence-based treatment.

In his first round as health minister, between 2009 and 2019, he reigned over the roll-out of what has since become the world’s largest HIV treatment programme. And in February, he launched another campaign, to find and treat 1.1-million people who know they’re HIV positive but are not on antiretroviral treatment (ART), by December.

But a day after the “Close the Gap” project saw the light of day, on February 26, all hell broke loose when the Trump administration pulled its funding for just over half of the US government-funded projects that would have helped the health department to achieve its HIV goals. The rest of the US-funded programmes will probably all end in September, at the end of the American government’s financial year.

Activists warn they’ve since seen a horrifying, fast-paced crisis playing out with ever increasing numbers of people skipping their HIV treatment, or not using prevention methods, because NGO clinics have closed.

They say they fear the collapse of the HIV programme they — and the minister — fought so hard for.

But Motsoaledi says activists are effectively lying because US government funding comprises only 17% of the country’s HIV budget of R46 billion.

“I want to state it clearly that propagating wrong information about the start of the HIV and Aids campaign in South Africa, in the matter that it is being done, is no different from the approach adopted by AfriForum and its ilk which led Trump to trash the whole country,” Motsoaledi, who is attending the World Health Assembly in Geneva this week, lashed out at the media at a press conference on May 15.

“I am saying so because we have already been phoned by the funders we have spoken to, who are asking us, why should they put their money in the programme that is said to be collapsing. Is their money going to collapse together with the programme?”

Other than an extra R1 billion from the Global fund for HIV, TB and Malaria, not a cent has been raised to replace US funds.

“The minister is in denial that there’s a crisis at all,” cautions Fatima Hassan, a lawyer who played a crucial part in the early 2000s to force the government to give people with HIV free ARVs, and who now heads the Health Justice Initiative. “We have been here before. No amount of finger pointing will save lives — only urgency, evidence, partnership, proper planning and resources will.

“Once again, South Africa will have to deal with the harmful public health consequences of not just the Trump administration, but also our own government’s failure to adequately plan for months now.”

Sex worker

Back in the parking lot, known as the Isle of Houghton, the Anova Health Institute’s six mobile clinics are standing idle.

Over the past three years, they’ve been used to test between 4 000 and 6 000 people each month for HIV in Gauteng — and to put those who tested positive onto ART treatment — in areas where government clinics are either too far from people’s homes to easily walk to or to reach people, such as teenagers or gay and bisexual men, who might face snickering neighbours or dismissive health workers at state facilities when they ask for condoms or HIV tests.

The US government is allowing Anova to keep only two of its mobile clinics and even those they can’t use because they no longer have money for staff to run them, says one of the institute’s public health specialists, Kate Rees. Since the funding cuts, Anova has had to stop almost all its work helping the government’s district health services to test and treat people for HIV and to hand out anti-HIV pills to prevent infection.

SIX IN A ROW: Anova Health Institute is only allowed to keep two of their US-sponsored mobile clinics after February’s funding cuts. (Anna-Maria van Niekerk)

SIX IN A ROW: Anova Health Institute is only allowed to keep two of their US-sponsored mobile clinics after February’s funding cuts. (Anna-Maria van Niekerk)

The stop-work order is already being felt in the data — March 2025 health department figures show that 30% fewer people took up ART in the City of Johannesburg than in March 2024, says Rees.

Johannesburg is one of the 27 health districts where Pepfar funded programmes. Among these were 12 clinics, across the 27 districts, with tailor-made HIV services for sex workers, transgender people, men who have sex with men and injecting drug users, groups with a much higher chance of getting HIV than the general population.

But because of population density, of 63 322 clients these clinics served, 41 996 — two-thirds — live in Johannesburg, Motsoaledi explained at the press conference.

WATCH THE HEALTH MINISTER’S PRESS CONFERENCE

As all these programmes have been shut down, people who got their treatment there, collected free condoms, lubricants or anti-HIV medication, now have to go to state clinics.

Motsoaledi says all the patients’ files have been transferred to the nearest government facility. But many have told Bhekisisa they’ve been refused services — often because government nurses tell them they don’t have transfer letters or they “don’t deserve to be helped”.

The HIV advocacy organisation Treatment Action Campaign and national sex worker movement, Sisonke, confirmed many more such experiences on a webinar hosted last week by Bhekisisa and the Southern African HIV Clinicians Society.

Motsoaledi says 1 012 clinicians and 2 377 non-clinician workers at government health facilities, most of them in Gauteng, are being trained to make key populations feel more comfortable to visit state clinics for HIV services.

But the health department has, in fact, been busy with such training for years, the former acting head of HIV in the health department, Thatho Chidarikire, told Bhekisisa’s TV programme, Health Beat in May 2023.

Despite that, severe discrimination against transgender people and sex workers persists, surveys by the Ritshidze group have shown.

One sex worker, who is pregnant and fearful she will transmit the virus to her child, told Bhekisisa this month: “I have defaulted on my ART for two months now. I have tried to go to a public clinic, but I wasn’t helped.

“Sex workers are seen as dirty people who go and sleep around. We even struggle to get condoms. People like me are now forced to do business without protection because it’s our only source of income and it’s the way we put food on the table.”

People on ART

Data commissioned by the health minister himself backs up HIV activists’ and scientists’ fears about the potential impact of US funding cuts on South Africa’s HIV programme.

One such modelling study shows that if South Africa fails to replace the Pepfar funds the country has lost, we might see between 150 000 and 295 000 extra new HIV infections over the next four years (in addition to the estimated 130 000 new infections we already have each year) and up to a 38% increase in Aids-related deaths.

With Pepfar data, the health department calculated it needs an extra R2.82 billion to get through the financial year and the minister’s own staff — including Nicholas Crisp, the deputy director general in the national health department who made the sums — told Bhekisisa in April without replacement funds, South Africa’s HIV programme would be “unsustainable.”

But at his press conference, Motsoaledi announced that the health department has, in fact, made what HIV scientists like Ezintsha head Francois Venter describes as “inconceivable” progress with getting people with HIV who stopped treatment, back onto their pills.

According to the minister, government health workers have managed to find close to half — 520 700 — of the 1.1 million people with HIV that they’ve been looking for and put them on treatment.

But, explains Anova’s Rees, those numbers are incredibly misleading.

“The minister didn’t subtract the number of people who were lost from care — those who stopped treatment or died — from the people with HIV who started or restarted treatment. If that was the number we were interested in, we would have reached our targets years ago,” Rees says.

She says that’s part of the reason why South Africa’s total number of people on ART has been lingering between 5.7 and 5.9 million for the past two years.

“Because of people who fall off treatment, we’re seeing static programme growth. So we’re not seeing significant increases in the number of people on treatment overall. That means that although the 500 000 people they say they’ve now put onto treatment may have been added to the treatment group, another 500 000 who had already been on treatment could very well also have stopped their treatment during this time. In many cases, it’s possibly the same people cycling in and out of treatment.”

The health department’s struggle, even with US government funding, to keep people on HIV treatment throughout their disease is also reflected in the second “95” of the country’s 95-95-95 goals. With the aim to stop Aids as a public health threat by 2030, these UN targets require us to, by the end of this year, have diagnosed 95% of people with HIV, have put 95% of diagnosed people onto ART and to make sure those on treatment use their pills each day, so that they have too little virus in their bodies to infect others (scientists call this being “virally suppressed”).

Right now, the minister said at his press conference, South Africa is at 96-79-94, which means we’re struggling to get people who know they’ve got HIV onto treatment, or to prevent people who are on treatment, from defaulting on drugs.

Covid vs the funding crisis

So how did South Africa get to a point where the health department and HIV scientists are yet again at loggerheads?

Not so long ago, on 5 March 2020, to be precise, shortly after South Africa’s first SARS-CoV-2 infection had been confirmed, then health minister Zweli Mkhize put the epidemiologist Salim Abdool Karim live on national TV. The scientist’s task was to explain to the nation what we knew about the unfamiliar new germ — the cause of Covid-19 — that was already causing havoc in the country. For two hours that evening, the nation sat glued to their TV screens to listen to science; an unthinkable scenario a few days before that.

Abdool Karim could do something Mkhize couldn’t — break down the cause of Covid, and where we were headed, in language everyone could understand. People were desperate for information and the government used experts — of which there were many — to keep South Africa up to date.

The important thing was that Abdool Karim wasn’t working for the government. He did chair the Covid ministerial committee, but, like the other scientists who served on it, he wasn’t a government employee.

He and others were merely people whose skills the health department was prepared to draw on — ironically, most of these were also HIV scientists, the same people who today feel they’re being snubbed by the government.

“We saw amazing leadership during Covid,” says Linda-Gail Bekker, an HIV scientist who heads the Desmond Tutu Health Foundation and was a co-chief investigator of the J&J Covid jab in South Africa. “[Because of the leadership], private funding followed. But we’re not seeing it this time around. My concern is it doesn’t feel like anyone [in the health department] is in charge.”

It’s not surprising Bekker feels this way.

The deputy director general position for HIV and TB has been vacant for five years, empty since Yogan Pillay, who now works for the Gates Foundation, left the position in May 2020. Health department spokesperson, Foster Mohale, says interviews for the position only started in the past few months.

Information hard to get

During the pandemic, there were daily press releases, vaccine dashboards and almost daily meetings with experts on the Covid ministerial committee. Now, other than the odd press conference, information that should be public, or opportunities for the government to respond to media or doctor’s questions — is non-existent.

We’ve seen that first hand at Bhekisisa. When we co-hosted a webinar on 8 May with the Southern African HIV Clinicians Society, we invited the acting deputy director general, Ramphelane Morewane, to answer clinicians’ and journalists’ questions. His office told us he was on leave in the days prior to it, but “would definitely be there”.

But Morewane didn’t turn up, no one was sent in his place, and no one explained why the health department couldn’t make it.

As a journalist during Covid, I had the numbers of people like the deputy director general in charge of vaccines on speed dial. This time around, I’m struggling to get mere copies of important government circulars, like the one that instructed government clinics how to hand out ART for six months at a time, and who qualifies for it.

HEADING: FIRST TAKE: THE HEALTH DEPARTMENT’S FEBRUARY CIRCULAR WITH INCORRECT GUIDELINES

Eventually, I got the first version through a non-government contact, but the health department had included incorrect guidelines for six-month dispensations. I’ve asked Morewane for the corrected circular several times, as well as the health department spokesperson and even the deputy director general, Sandile Buthelezi, whom I’ve always found helpful.

I’ve received nothing.

Why a corrected government circular that will help to clear up confusion has to be kept a secret is a mystery to me, and many of the doctors whom I’ve spoken with feel the same way.

It’s as if government decision-makers now regard the scientists and activists the health department worked with so well during Covid as enemies, rather than allies, some experts say.

“We need to all put our minds together in a room and work out what are our best buys and how do we get those out to people who need it the most,” explains Bekker. “The government can’t solve this problem on its own.”

The head of the Southern African HIV Clinicians Society, Ndiviwe Mphothulo, concurs: “History tells us the reason our ART programmes have been so successful is because the government worked with civil society. People who won’t learn from history, repeat the mistakes from history.”

Transwoman: ‘I couldn’t even get condoms’

Back in Hillbrow, close to the parking lot with the now unused mobile clinics, a young transwoman is considering buying her ART pills on the black market. By the end of May, the three-month supply of ART she got from the US-funded Wits Reproductive Health Research Institute clinic, which closed down in February, will run out.

“I’m anxious and depressed, each day,” she says. “At the Wits clinic, I got my treatment without being made fun of and I got self-testing kits for my sexual partners. But, most importantly, I could get mental health for free.

“My friends visited the government Hillbrow clinic the other day. I couldn’t even get condoms, let alone treatment.”

Additional reporting by Anna-Maria van Niekerk. Graphics created by Zano Kunene and Tanya Pampalone.

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.