Who should get SA’s first batch of lenacapavir jabs? Here’s how different scenarios compare. (Mufid Majnun/Unsplash)

What’s the best way to divvy up a shipment of medicine that will cover less than half the people per year than should ideally be reached to end Aids in South Africa?

That’s what public health experts discussed at a meeting organised by the health department and the country’s national Aids council, Sanac, in October about how to allocate the batch of lenacapavir (LEN) shots South Africa is getting, thanks to a donation of $29.2-million (about R500-million at the latest exchange rate) by the Global Fund.

The money can buy enough doses of the new six-monthly HIV prevention jab, which is almost foolproof in protecting people from getting infected with HIV through sex, to cover about 456 000 people over two years.

But modelling results presented at the meeting in October show that up to four times as many people — between one and two million — will have to take the medicine every year at least once if the country wants to get new HIV infections down so low that 15 years from now Aids won’t be a public health worry anymore.

Because of the limited initial supply, the medicine will have to “be managed strategically”, said Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi, adding that for the roll-out of LEN over the next two years to make a real difference in the country’s HIV infection rates, the focus has to be “on those populations at highest risk”.

These groups, modelling showed, are: female sex workers; gay and bisexual men; teen girls and young women; and pregnant or breastfeeding women.

But who should get what slice of the pie once the medicine is available in public clinics? And are numbers alone what would drive decisions?

Here’s what the modelled data shows.

A science and an art

To get a sense of what the result would be of splitting the available batch of shots among the four target groups in different ways, researchers used a compartmental mathematical model (Thembisa) to run some numbers.

This is basically an equation made up of a bunch of calculations using specific input values, with the combined answer being an estimate of a certain outcome in real life — in this case, the number of new infections that could be prevented by different groups of people getting the six-monthly anti-HIV injection. And because it’s easy to change the input values — in this case, the proportion of the batch of medicine going to different groups of people — the effect of many different combinations can be forecast.

“Modelling is sometimes somewhere between an art and a science,” says Lise Jamieson, who headed the study presented at the meeting. But because the model uses maths to describe real-life information based on plausible underlying assumptions, it’s a good way to get an informed conversation started — with numbers to back it up, she says.

What does data that drives decisions look like?

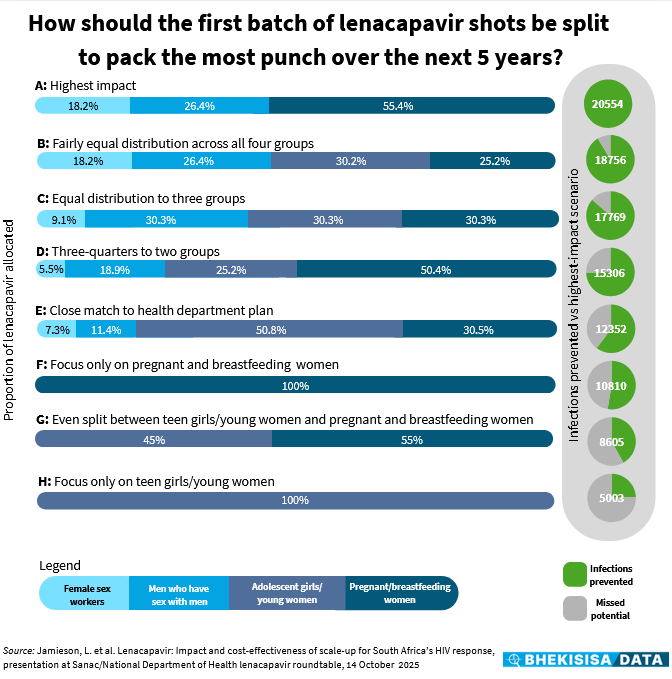

The model, which generated 490 combinations, showed that if just over half of the available shots are given to pregnant women and breastfeeding moms, about a quarter to gay and bisexual men, and around a fifth to female sex workers (scenario A), there could be 20 554 fewer new HIV infections over the next five years.

This will give South Africa the best bang for our buck for its LEN roll-out with doses sponsored by the Global Fund. (This donation will only be enough doses for two years, and the modelled data estimates the impact of this roll-out over the next five years; during phase 2 of the national roll-out the government plans to buy LEN with the country’s own funds.)

The worst outcome — from the perspective of the number of infections prevented — would come from giving all of the available shots to women between 15 and 24 years old, the group among whom about a third of new HIV infections in South Africa occur, but at the same time also a population who hangs out in many different places, which makes them hard — and costly — to reach and follow up (scenario H).

Doing this would likely prevent only about 5 000 new infections over the next five years — roughly a quarter of what could be achieved with the highest-impact combination (scenario A).

For Aids to end as a public health threat, the incidence rate needs to be reduced to 0.1% or below. For 2024, for which there were 172 994 new HIV infections, that number should therefore be as low as 65 000 new infections if we want to end the epidemic.

Finding middle ground

Because 490 different combinations can be overwhelming to present visually, we picked six scenarios between the two extremes — the highest-impact option (panel A) and the one that would prevent the least new infections (panel H) — as a starting point, to see how they compare.

For example, panel E shows a combination that closely matches the roll-out plan the health department suggested at the October meeting. In this scenario, roughly half of the shots would go to teen girls/young women, just under a third to pregnant women and breastfeeding moms, and the rest would then be split between female sex workers and gay and bisexual men.

This combination could prevent around 12 350 new infections over the next five years — about 60% of the best possible outcome. (The government’s suggested plan also includes transgender people, but because this is a very small part of the general population, this category was incorporated into one of the other groups in the model; we selected a combination from the data that would be a close match.)

Both women between 15 and 24 and those who are pregnant or have just had a baby have a big chance of contracting HIV, and so it would seem sensible to focus mostly on these groups when deciding who to give the shots to.

For example, current estimates show that about a third of new infections in the country are in teen girls/young women, even though they make up only about 8% of the total population.

Pregnant and breastfeeding women too have a bigger chance of contracting HIV than the general population, Dvora Joseph Davey, an associate epidemiology professor at the University of Cape Town told Bhekisisa previously, because they often don’t use condoms, (as there’s no risk of falling pregnant when they have sex during their pregnancy) and also because of changes in the cells of the female reproductive system during pregnancy that can make it easier for the virus to get a foothold, Joseph Davey explained.

However, focusing only on pregnant women and breastfeeding moms or splitting the shots roughly equally between that group and women younger than 24 (panels F and G) would prevent at most about half of the infections that could be avoided with the highest-impact combination.

Although the model shows that it would be good to target pregnant and breastfeeding women and doing so would be smart for logistical reasons (because they go to antenatal and baby clinics, so they’re easy to find and monitor), “we can’t target only them”, says Jamieson. In fact, in such a scenario, only around half as many infections would be prevented as would be possible with the highest-impact combination (panel A).

Including a combination of groups seems better. For example, if about three-quarters of the shots are made available to two groups — 50% to pregnant and breastfeeding moms and 25% to teen girls/young women — just over 15 300 new infections could be prevented over the next five years. This is about 75% of what would be possible in scenario A.

Things look better still when the available shots are split more evenly between at least three groups, but ideally all four (panels B and C), with the number of new infections that could be prevented sitting between 86% and 91% of what’s predicted for the highest-impact scenario.

Says Jamieson: “The numbers show that the best impact could be achieved when a combination of groups is considered.”

Build your own

Because there are many more scenarios than the eight we highlighted here, we also put together an interactive dashboard, which includes 261 combinations — just over half the number in the original data set — for you to explore yourself.

As the model is made up of “compartments” — meaning specific groups — choosing a value for one group defines the set of possible values that can be chosen for the other groups.

In the dashboard, pick a value from each of the four drop-down boxes.

Say you start with choosing a scenario in which teen girls/young women get 60% of the available shots. That means 40% is left for other groups. This can be split, for example, so that 10% goes to pregnant and breastfeeding moms, which would leave 30% for the remaining two groups.

You could then choose to give all of that to gay and bisexual men and nothing to female sex workers, or, say, 11% to sex workers and offer the remaining 19% to gay and bisexual men.

The number of infections averted is shown in the panel below the selection boxes, with a summarising pie chart to show how this outcome compares with what could be achieved in the highest-impact scenario.

For easy reference, we also provide the combination that is close to that suggested by the health department and the model’s highest-impact scenario at the bottom, together with the number of infections that could be prevented in each case.

Click the reset button to choose a different combination and see how the outcome changes.

Data-driven approach

Following the numbers can help decision-makers make smart plans, as South Africa saw more than 20 years ago, when the Human Sciences Research Council’s first national survey in 2002 showed that just over 11% of South Africans older than two years were HIV positive. It was a turning point in the country’s public health history — and something Aids denialists could not argue with.

Now, again, the government says that its “approach is firmly data driven” at what the health minister called “a pivotal moment in South Africa’s HIV response”.

But to make the best decisions based on numbers, the realities of getting the medicine to people also need to be taken into account — something that will have to be carefully thought through in the wake of this year’s funding cuts having caused many places serving some of the high-risk groups identified by the modelling to close or scale down.

The deputy director general for HIV in the national health department, Nonhlanhla Fikile Ndlovu, says for the department’s allocation of doses to clinics, districts with the highest rates of new HIV infections were chosen, as well as those with large proportions of groups of people who have a higher chance of getting HIV.

“But in reality, we can only roll out LEN with facilities who are able to do so. We therefore also looked at the performance of clinics with the daily HIV prevention pill, which we started to roll out in 2016, as that gives us a good idea which facilities are able to administer HIV prevention medication and keep track of clients. We therefore selected clinics in the highest burden districts whose past performance shows us they are well-equipped and who were not severely affected by the US government’s stop-work order in January. ”

Says Jamieson: “The best way to think about rolling out this initial batch [of shots] is to focus on creating as much demand [for HIV prevention medicine] as possible, irrespective of who we’re giving them to. For me, if we can create demand in the general population and within people with high risk, that’s a winner.”

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.