Dry: In Homu in Giyani, Limpopo, 19-year-old Reason Baloyi has to collect water every day after school from a stand tap in the village. Photo: Oupa Nkosi

NEWS ANALYSIS

For more than two decades interventions by provincial governments into failed municipalities have not worked — about 100 remain in crisis and cannot provide residents with the most basic of services.

The high court order that the Makana municipal council in the Eastern Cape be dissolved for failing to fulfill its constitutional obligation to provide residents with services is but one of the examples of a broken local government system.

Beyond these interventions experts also warn that the government needs to take a serious look at how municipalities are run.

Section 139 of the Constitution, which provides for provincial intervention in local government, has never been a silver bullet, said Professor Jaap de Visser, a governance specialist at the University of the Western Cape’s law faculty and director of the Dullah Omar Institute.

“I did my master’s thesis in 1998 on interventions. The first in terms of section 139 was on the go in what was then called Butterworth, which later became Mnquma local municipality. It has since been intervened into two or three times. More than 22 years later we are still intervening in that municipality. So clearly, the whole concept of interventions is not a silver bullet,” he said.

“From a justice point of view, I really think it is necessary to get the province to take action but the overall system of local government needs serious overhaul.”

The section 139 interventions require a provincial government to a) issue a directive to the municipalities; b) assume responsibility because the municipality could not fulfil an obligation; c) dissolve the municipality; d) take steps to ensure a municipality adopts the budget; and e) have a recovery plan to secure the municipality’s ability to meet its obligation.

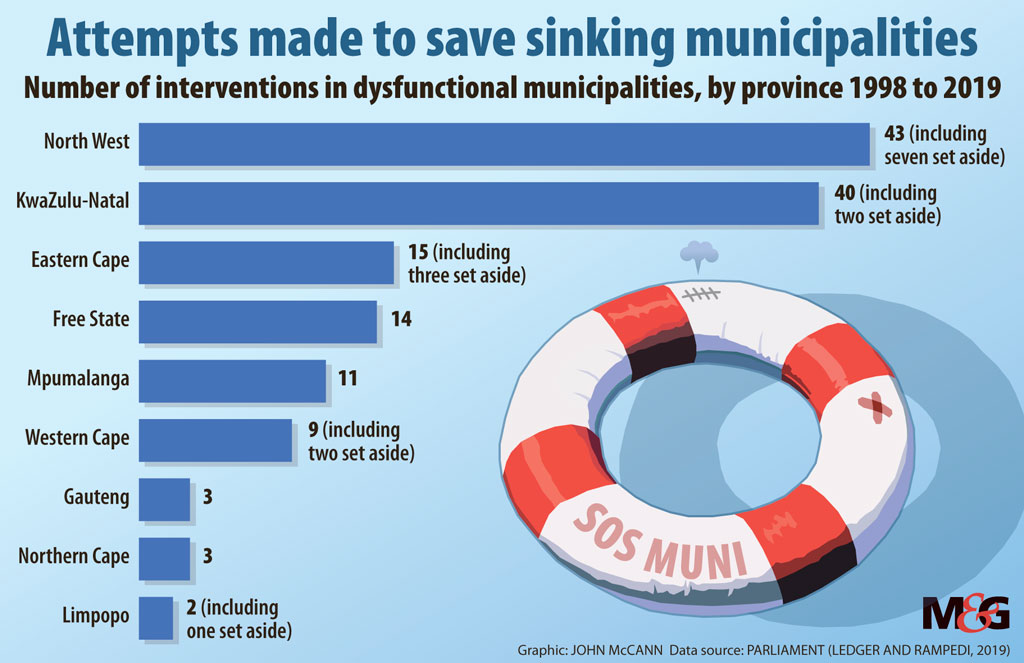

Research by the Public Affairs Research Institute (Pari), which focused on the practice of placing municipalities under administration, found that about 140 municipal interventions have been attempted in the past 22 years.

Pari’s research, titled Mind the Gap, found that of the 140 interventions 48 were repeat offenders. The researchers also found that the worse the state of the municipality before the intervention — such as a financial collapse, a breakdown in governance structures and the collapse of infrastructure — the less likely it is to be able to return to a stable financial and operating position. This is particularly true of smaller municipalities.

“Our 2018 investigation into section 139 interventions showed conclusively that the majority of interventions reviewed could not be termed a long-term success.

“A significant number of interventions failed to record more than only marginal improvements in the selected indicators and, certainly, the municipality could not be considered as having recovered to operational and financial good health. In some cases, the state of the municipality deteriorated during and after the intervention,” reads the report.

Dry: To supply residents with water in Ugu district municipality on the KwaZulu-Natal South Coast, trucks must transport water to the reservoir. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy

Dry: To supply residents with water in Ugu district municipality on the KwaZulu-Natal South Coast, trucks must transport water to the reservoir. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy

When presenting the report at a seminar hosted by the Socio-Economic Rights Institute, Pari’s senior researcher, Dr Tracy Ledger, said very often financial problems are at the heart of service delivery problems.

“Why do we have this very high failure rate? The interventions come too late, the wrong sections are being implemented. Linked to that is the fact that executive obligation has been misinterpreted. Administrators are used incorrectly.

“All of the parties, provinces, national Cogta [cooperative governance and traditional affairs department] and national treasury are negligent in their mandatory obligations,” she said.

Ledger explained that the interventions are taking place when the municipality has been in a state of total collapse for an extended period.

“We’ve been in a municipality where the problems were so serious that before an intervention took place every single moveable asset in that municipality had been repossessed twice by the municipality’s creditors. The only reason that municipality had a desk or a chair or a computer was because a local mining company had lent it to them. There wasn’t one single working water meter in that municipality and that was before the intervention.”

Another problem with the interventions is the time frame given to administrators to fix the problems, according to De Visser.

Wet: Water flows freely through Standerton – but it’s an overflow from a broken sewage system. (Photo: Delwyn Verasamy)

Wet: Water flows freely through Standerton – but it’s an overflow from a broken sewage system. (Photo: Delwyn Verasamy)

“That’s the problem with this solution. You cannot have an administrator come into a collapsed municipality and be expected to turn it around in three months [when a municipal council has been dissolved]. That’s impossible. Second, it’s all good and well to run the election in 90 days, but given the proximity of everything the same council could be voted right back in,” he said.

One case study that points to the possible inefficiency of interventions is in the Makana municipality. In January, Judge Inga Stretch of the high court sitting in Makhanda, lashed the municipality for its failure to meet the constitutional obligations it has to the residents.

In the landmark judgment she ordered the dissolution of the council and that the municipality be placed under administration.

Local activists, including the Unemployed People’s Movement, had approached the high court in 2019 arguing for the council to be dissolved because of its failure to provide basic services such as water. None of the respondents in the case, including the municipality, the province and various government departments, disputed that it was in breach of its constitutional obligations.

The provincial government had on two occasions intervened in the municipality in terms of section 139. None of the interventions resulted in the desired change.

The provincial government has petitioned the supreme court of appeal to overturn the judgment.

The chairperson of the Unemployed People’s Movement, Ayanda Kota, said they would continue to fight until the municipality provided residents with basic services.

Wet: Pigs root in slurry in Sebokeng in the Emfuleni local municipality where sewage flows from old infrastructure that is also polluting the Vaal River system. (Photo: Delwyn Verasamy)

Wet: Pigs root in slurry in Sebokeng in the Emfuleni local municipality where sewage flows from old infrastructure that is also polluting the Vaal River system. (Photo: Delwyn Verasamy)

“It is quite clear the province is more concerned about the precedent that this case might set and less about the fact that the municipality cannot deliver on its constitutional mandate. I believe that they will take it all the way to the constitutional court.

“But this is still a lesson for all municipalities that do not work or have collapsed. People have the right to recall councils that are inadequate and corrupt. People will no longer be used as instruments for political parties and when elections are over they are discarded,” said Kota.